|

|||||||||

INTERVIEWS

Classical Editor: Rob Barnett

Music Webmaster

Len Mullenger:

Len@musicweb-international.com

|

INTERVIEWS |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

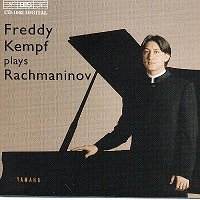

Interview with Freddy Kempf and Marc Bridle April 2000

Meeting Freddy Kempf can be a humbling experience. Not yet 23, he is already well on his way to becoming a pianist of considerable greatness (his new Rachmaninov disc is very fine indeed). The paradox is that he is also so incredibly normal and charming, at least by the standards we have come to expect of our musicians. I arrive early for our interview (which overruns) - enough for other artists to throw a tantrum or otherwise. Not Freddy, who is happy to start early and carry on. He makes coffee, and slides around the sitting room in socks. His mobile rings, he apologises. He hates hotels and flying, and likes nothing more than driving back from a concert late at night - even if it is several hundred miles away from his North London home. Home is where he loves to be. And he now has a parking space for his car, a passion he mentions often (even if his motor insurance is staggeringly expensive - "It's because musicians work where drinks are sold"). Nowadays he prefers to have the TV on as background music, and relaxes by playing computer games (strategy and rôle play mostly). Gadgets and the Internet (where he has recently started using Tesco's internet service when he fell ill) are much more his métier nowadays. Just normal, even if his pianism isn't.His love affair with Russia is well known (his young wife is Russian), and his new Rachmaninov disc is in part a reflection of this. The opening work is the great Second Sonata, a titanic piece that Kempf has recorded in the original 1913 version. He has played both the 1913 version and the 1931 rewrite in near equal measure, but his views on the merits of the original are compelling. "There are so many beautiful things in the 1913 version which Rachmaninov cuts out of the later version (although you could argue that the 1931 is more concise and has a better structure). Although he was a better composer by 1931, he didn't have that spontaneous inspiration which marks out the earlier version. He was definitely rewriting the work rather than writing a completely new work, unlike say the Brahms Op. 8 Piano Trio which was revised 30 years later but which is certainly a completely different piece. The 1913 is more pianistic, the textures are more like the popular Rachmaninov of the Second and Third concertos." He doesn't find anything different in the mood of the pieces, "but the musical impact, the sound of the original work with its greater number of notes makes it more compelling". The couplings were designed in part because of their familiarity to Kempf, but "were in keeping with works from the period of the Second Sonata. The Etudes have a similar texture and colour".

He has played the Rachmaninov concertos often (the Third at the final of the Tchaikovsky competition). Although he has learnt both of the cadenzas to the Third, he plays the larger one more often. "Most pianists, if they are comfortable with the larger one will play it. Partly this is ego, but it is also a wonderful cadenza". He will be doing the Rachmaninov Third at the end of the year (on a UK tour of fifteen concerts), although admits that he has played the piece less often than he would have been expected to. It is with a certain irony that he tells me he wanted a balance for these concerts and when he shows me the itinerary I can see what concert promoters mean by balance: the Rach 3 appears fourteen times on the list, the Paganini Variations just once. "I don't know why they chose that, I would have preferred the Second concerto". Choice of concerto repertoire is something which I think concerns the young Kempf. "At this stage of my career I cannot really choose what I want to play. It is quite amusing that I am doing the Beethoven Fourth so much this year because it is not a piece I have performed that many times, and one that I would not choose actively myself, even if I had been able to choose a Beethoven concerto".

For many pianists the instrument on which they play is often important. I ask Kempf why he recorded the Rachmaninov on a Yamaha. In keeping with his lack of mystery, the answer is less revelatory than one might have expected. "It was the best instrument that we could get in the studio at the time and without spending too much money. It was the best compromise, although I didn't use the same piano on both the Schumann and Rachmaninov discs. I did try many brands of pianos - but it is more difficult in Stockholm (where he records with BIS) than it is London". As to the sound, "I am one of those people who believes that you can get any piano to sound like any other if you have a good technician". Mention of Stockholm takes us onto recordings themselves. Two discs in two years sounds little, but again the whole story behind this is much more complex than it seems on the surface. Kempf is contracted to make a recording every six months, but it is not so much an antipathy to the recording process as the vagaries of editing and completion, and then distribution, which makes his recorded output seem slim. The Rachmaninov should have been released last year (but will now appear on May 1), and he has in fact already recorded his third disc (of the last three Beethoven piano sonatas). He has his own thoughts on why the Rachmaninov - which he recorded in August 1999 - may have been delayed. "It was a very long time before I got the first edit, and I think because it has such complicated textures the editors had a tough time just listening to it and wondering what was wrong and what wasn't".

I mention to him that some pianists deliberately avoid certain repertoire. I quote Brendel and Barenboim, who don't play Rachmaninov, and ask Kempf if he has any antipathy towards any particular composers. "Not yet. I'm trying to keep a very open mind, but if I don't like a composer now I may do so in five years. Because of that, with BIS I will record a complete new recital of works by a new composer every six months. I won't repeat a composer until this series is done. I've done that so I don't specialise too early. I could quite easily have done more Schumann and then find out in ten years time I'm actually more suited to another composer. The next disc is Beethoven, and this is then followed by Chopin in July and Liszt in January. I will do a Bach disc and then a Schubert one. Recording itself I don't enjoy. I love being on stage and having an audience there. I like the fact that in a concert you can try out things and do something exciting. On a record you have to be careful. If it's in bad taste you can't get away with it. It's always going to be there. But in a concert you can say, 'well it didn't quite work'. I do admit to not liking the recording medium as much as concerts. I do prefer having an audience".

This leads us onto contemporary music. Kempf would love to play more of this, but is both aware of his age and what the markets need to achieve sales. "It is a case of what is in demand. A lot of promoters, even if you offer Prokofiev - I'm getting feedback saying 'can you change that for something more popular'- don't want this. At my age I can't veto everyone, I have to fit in with what others want. You'd probably be surprised (I'm not, unfortunately) at how conservative people's tastes are, especially when it comes to recording. People say, well Rachmaninov sells so I just have to fit in with the markets. I don't really know that many twentieth century works, but I'd be interested to see what becomes great in the future". Although he likes the works of the Second Viennese School, he again feels unable to record Berg or Webern at present, but hopes at least one of his future BIS discs might be of Bartok or Debussy.

Unlike many musicians of his age, Kempf has a startlingly mature interest in chamber music. "With the piano it's very easy for your life to become very solitary. You're always the soloist, or you tell the conductor what to do. And with recitals it's the same, you just do what you want.. Often the other people around you won't be pianists. It's not easy to socialise, and especially with me I think I'm the type of person who might become arrogant very quickly if I was always in that situation. It's nice to sit in a chamber group and be told 'you're playing rubbish', or to be told what to do. I learn a lot from the people I work with and love knowing that what you are playing is not the only important thing. It does apply to other things, sometimes for example a clarinet might be harmonising a solo in a concerto, or the violins have a solo. Since I am used to chamber music I can let that happen and just sit back and be able to hear that and not worry about playing the wrong notes or getting lost".

He continues, "It's sort of in-between. Playing for a symphony orchestra you have so many people on a stage and you're bonding with a conductor and the orchestral players. Sometimes there is so much going on it's not easy to get agreement and inspiration from each other. With chamber music you have two or three people you are working very closely with - when you are accompanying them you can almost sit back like a member of the audience and appreciate what they're doing and when you're playing you can feel them responding to you. For me its one of the most fulfilling mediums to play in. Especially with the piano trio you can be as selfish as you want with each instrument treated as a solo."

His craving for chamber music came from the Marlboro Festival. "I remember being told I'd have to rehearse the Mozart Piano Trio on the first day. I listened to the Beaux Art Trio to get an idea of tempi and walked into rehearsal room and there was the cellist from the CD cover sat in front of me. Midori was there, and Hilary Hahn. All of these people were there and they just wanted to play chamber music. Even if you played with the cellist of the Guarneri Quartet, who had played with Rubinstein and had played the piece more than 200 or 300 times, you always felt comfortable. If you had a valid idea they would listen to you, it was just a wonderful experience". At no time during our interview does Kempf seem more at ease than when talking about chamber music.

Future plans will include some Prokofiev (despite the misgivings of the marketeers), and he talks with much enthusiasm about Busoni, much of whom's music remains unrecorded. Modest as ever, he isn't quite sure how he sees his career developing. After having had so much exposure after the Young Musician of the Year he feels his career did drop off a bit - there was a minor problem with technique that he refers to, when he wasn't playing as well as he could. But he is anxious that his chamber career develops as well as his solo career. He wants to keep playing at concert halls the size of the Wigmore, but admits that in may countries halls of this size do not exist. His Japanese debut at the Suntori Hall initially caused him some problems. "It's so large I didn't know whether to over pedal or under pedal. Fortunately, Mitsuoko Uchida, whom I met through Marlboro, was there and I was able to ask her". Much as Stockhausen complains about concert halls being too small, Kempf rather laments the decline of the medium sized concert venue. "Basically, they're either 200 or 2000 seater halls, with very little in between".

He would love to go to Russia more often. "It's difficult with the security issue, but I'd love to go to the smaller towns. It's very difficult to get to the countryside without fear of being attacked by bandits. There are some orchestras in the Urals I'd love to play with and would love to go on the Trans Siberian railway. As it is, I tend to play mostly in Moscow. I do have something of a cult following there, even though I didn't win the Tchaikovsky competition. But I find they love music and they genuinely respond warmly".

He talks about the Russians uninhibitedness when it comes to music and their willingness to clap. "I was surprised during the early rounds of the competition where they don't usually clap. I played some Chopin Etudes that went well and they didn't clap at all. I then played some grade four Tchaikovsky piece and they burst into applause. It surprised me. When it comes to encores it's a bit more difficult. Sometimes you can see the hall emptying and you don't really know whether you should play one. In Russia, though, they wait until there is no chance of you coming back onto the platform before leaving".

Kempf's modesty is very self-evident in my final question. He doesn't fall into the trap of offending any of his colleagues by nominating a favourite living pianist, although admits to being something of an "uncritical listener" in that he likes bits of most pianists. He says its a bit of a cliché, but he loves Horowitz , "he played with such character" and mentions Cherkassky. " It's such unselfish musicianship when they do take indulgences, which may be they shouldn't, and you love them for that. I would have loved to have heard Rachmaninov live. You don't know how comfortable they were in the recording studio, but I know from my own experience that even moving a microphone a couple of inches can often make you sound unrecognisable".

Freddy Kempf is a musician with his feet firmly rooted on the ground. His career is developing at his pace. Don't expect him to play at Carnegie Hall one night and La Scala the next, because he won't. His artistry and insight into the music is growing exponentially with each new disc he releases. Expect some miraculous performances indeed in the coming years.

Marc BridleCD Reviews Rachmaninov Beethoven Chopin

Since April 2000 you are visitor number