CD Reviews

CD Reviews MusicWeb

Webmaster: Len Mullenger

Len@musicweb.uk.net

[Jazz index][Purchase CDs][ Film MusicWeb][Classical MusicWeb][Gerard Hoffnung][MusicWeb Site Map]

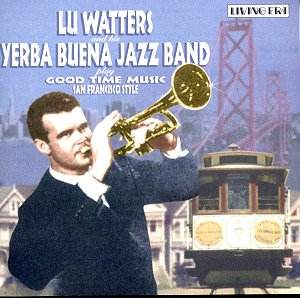

Lu Watters and his Yerba Buena Jazz Band play

Good Time Music San Francisco Style

Muskrat Ramble

At A Georgia Camp Meeting

Original Jelly Roll Blues

Maple Leaf Rag

Come Back, Sweet Papa

Fidgety Feet

London Blues

Sunset Café Stomp

Daddy Do

Milenberg Joys

Riverside Blues

High Society

Cake Walkin’ Babies From Home

Tiger Rag

Working Man Blues

Big Bear Stomp

Antigua Blues

Chattanooga Stomp

Jazzin’ Babies Blues

Ory’s Creole Trombone

Friendless Blues

Copenhagen

Emperor Norton’s Hunch

Alcoholic Blues

My Little Bimbo Down on the Bamboo Isle

Lu Watters and his Yerba Buena Jazz Band

Recorded 1941-50

![]() LIVING ERA CD AJA 5550

[77.18]

LIVING ERA CD AJA 5550

[77.18]

AMAZON UK Budget price

Lu Watters and the YBJB attracted, and I suppose continue to attract, a rather bad press. Seen as derivative revisionists of a cornball stripe their place in the historic re-evaluation of New Orleans music has been consistently overlooked. And yet their early 1940s standpoint predated the majority of "authentic" recordings made of first or second-generation jazzman in the Crescent City in that decade. And the YBJA acted as a catalyst for numerous bands and set a standard that others looked towards emulating. There was certainly some corny material along the way but the serious business of the two beat, tuba laden, two trumpet frontline embraced a great deal else; King Oliver, Morton, some obscure blues, rag time, the ODJB and some authentic-sounding originals. It was essentially a repertory band based explicitly on the Oliver band of the early 1920s and the Watters-Bob Scobey team fused with Turk Murphy’s pungent trombone and clarinettist Ellis Horne (later Bob Helm) to produce rip-roaring and exciting ensemble, full of guts and gusto.

There are plenty of highlights – from the fine recreation of the Original Jelly Roll Blues to Murphy’s big fat trombone on Come Back, Sweet Papa with an ebullient ride out chorus, one of the band’s specialities. Watters himself plays a good, solid lead and dovetails expertly with Bob Scobey and they dig up some arcane stuff along the way; heard Fred Longshaw’s Daddy Do recently. Ever? Textures can be thick, it’s true, and Ellis Horne’s clarinet often gets submerged in the balance but that two beat feel is good for Tiger Rag and makes it sound fresh and invigorating rather than tired and stale. Working Man Blues has a real swing to it and there’s some driving lead in Big Bear Stomp. Helm struggles in Antigua Blues where the rinky-dink banjo is a decided liability as well but Wally Rose contributes pleasant raggy piano in Emperor Norton’s Hunch, Watters’ own biggest hit. The last two tracks, which featured the 1950 band show a change of direction; rather more easy listening, with a cornball-ish vocal and less of the doctrinaire New Orleans esprit. But the confidence of the band remained untouched and its strident drive remained a tonic.

The transfers are in the main in very decent sound, and the notes by Peter Dempsey cover the field justly and well.

Jonathan Woolf