CD Reviews

CD Reviews MusicWeb

Webmaster: Len Mullenger

Len@musicweb.uk.net

[Jazz index][Purchase CDs][ Film MusicWeb][Classical MusicWeb][Gerard Hoffnung][MusicWeb Site Map]

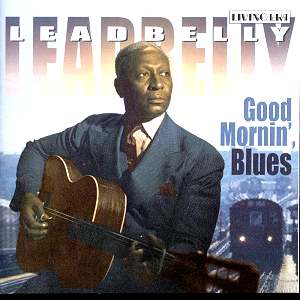

Leadbelly – Good Mornin’, Blues

rec. 1935-45

![]() LIVING ERA CD AJA

5633 [77:05]

LIVING ERA CD AJA

5633 [77:05]

Crotchet Budget price

1. Good Mornin' Blues [2:50]

2. Rock Island Line [2:31]

3. Pick A Bale Of Cotton [2:59]

4. Mister Tom Hughes' Town [3:04]

5. Looky Looky Yonder/Black Betty/Yallow Women's Door Bells [3:05]

6. Bourgeois Blues [3:21]

7. Poor Howard/Green Corn [3:21]

8. Whoa Back Buck (Ox Driver's Song) [3:07]

9. Boll Weevil [3:08]

10. Gallis Pole [3:09]

11. Easy Rider [3:08]

12. Midnight Special [3;02]

13. New York City [3:00]

14. You Can't Lose A Me Cholly [3:01]

15. Leaving Blues [3:33]

16. Alabama Bound [3:03]

17. On A Monday [2:54]

18. I'm On My Last Go Round [3:08]

19. Can't You Line 'Em [2:52]

20. How Long Blues [2:13]

21. John Hardy [4:08]

22. Eagle Rock Rag [2:45]

23. Out on the Western Plains [1:33]

24. Bring Me L’l Water, Silvy [0:52]

25. Take This Hammer [2:58]

26. Goodnight, Irene [2:24]

Leadbelly [Huddie Ledbetter] (guitar, tap-dancing, button accordion, piano) with The Golden Gate Quartet and Sonny Terry (harmonica)

One of the more frustrating things about Leadbelly’s legacy is the rather unhelpful recording quality of his surviving discs. Some of the Musicrafts, Asch and Bluebirds were definitely not state-of-the-art though in fairness that was not a feature characteristic simply of them. Portable recording units of the rough and ready kind were certainly staples for many blues singers of the time.

But of course Leadbelly wasn’t a blues singer, though he did sing the Blues. He was more in the Songster tradition, a singer and guitarist – and as this enterprising selection shows, multi-instrumentalist – of catholic tastes. Country songs, field hand songs, penitentiary chants, ballads and traditional survivals, as well as the Blues, laced his repertoire – as indeed did contemporary popular song. This last taste might not always have been to the approval of his young admirers, who wanted him to delve into his archaic musical knapsack – much as Leadbelly’s contemporary, the jazz trumpeter Bunk Johnson (with whom Leadbelly performed) was frowned on when he essayed swing era standards.

Leadbelly’s enduring legacy lies in the quantity of songs that he, effectively, codified as his own. The line from Leadbelly to Pete Seeger, to Bob Dylan, to the skiffle craze in Britain exemplified by Lonnie Donegan and indeed beyond is a potent one. As Digby Fairweather’s notes remind us that influence was still apparent, if unacknowledged or unappreciated, well into the 1970s.

The extent to which the skiffle players simplified and jollified Leadbelly can be heard in Rock Island Line where Leadbelly’s twelve string subtleties – the chugging of the railroad rhythm and its associated subtleties – became ironed out in a sort of kinetic and vulgarly enjoyable fabrication. Try to listen to Leadbelly’s infectiously driving rhythms on Leaving Blues, an example his followers could barely hope to emulate.

An enduring part of his legacy remains the chain gang holler and as a convicted murderer he knew what he sang about. These songs are reminiscent of the Murderers’ Home songs recorded somewhat later in field trips to Parchman Farm and reminiscent too of the many recordings made of prisoners in the State Penitentiary, Angola (Rounder and Arhoolie have done excellent work in CD reissues though many of us will remember the LP transfers). Leadbelly’s own songs must have made a significant contribution to enthusiasm to record this important feature of penitentiary life.

We hear him tap dance, play his original instrument, the accordion, and play some rudimentary but effective piano. He essays politicised songs, declining to be "mistreated by no bourgeoisie" and is joined by the influential (but to my ears sometimes tiresome) Golden Gate Quartet. Being a braggart songster it’s amusing to hear him appropriate the words of another braggart, Jelly Roll Morton, in Alabama Bound, the copyright of which was claimed by Leadbelly and John and Alan Lomax. So maybe the Lomaxes, who recorded Morton in the Library of Congress, fed the guitarist some of Morton’s choice lines.

Sonny Terry adds stature to the tracks where he joins Leadbelly but their collaboration on How Long Blues is done down by Leadbelly’s weak falsetto – and also by the unholy cheek of the songster claiming Leroy Carr’s song as his own.

Still, this is a most attractive compilation, sympathetically transferred and well annotated by Fairweather. The run of songs is especially effective when we are presented with the multi-instrumentalist in action and with his esteemed collaborators. Then we really do see Leadbelly as the versatile songster whose presence up North was an inspiration to musicians, polemicists and fans alike.

Jonathan Woolf

Comments received October 2008

Reading Woolf's notes on Leadbelly's Good Morning Blues album I noticed two misstatements. Here's the quote: "Sonny Terry adds stature to the tracks where he joins Leadbelly but their collaboration on How Long Blues is done down by Leadbelly’s weak falsetto – and also by the unholy cheek of the songster claiming Leroy Carr’s song as his own."

Here's the corrections:

1. "Leadbelly's weak falsetto" is actually Sonny Terry trading off his harp sound with his voice sound -- done so well it's sometimes hard to hear the transition. This action is a favorite of Sonny.

2. Leroy Carr's lyrics are considerably different than Leadbelly's. In addition Leadbelly's words have quite a bit more "poetry" than Leroy's. Also, it's pretty typical of country blues singers back in the early part of the 1900s to take bits and pieces of various songs (some of them their own and some of others) and stitch them together into new songs, or add verses to other, standard, songs. Common among many of the original folk singers of the day. In addition Leadbelly didn't have "unholy cheek" --- because he was the most accomplished musician of his genre, he knew it, and all his audiences knew it.

If it's convenient for you, adding a note to Woolf's notes would be appreciated.

I'm a folk musician who specializes in singing Leadbelly's repertoire in various parts of the US South.

Cheers,

Bill Schenker

Jonathan Woolf adds

The 'unholy cheek' lies in taking a tune copyrighted by Leroy Carr and claiming sole composer credit, thus pocketing the royalties.