BUY NOW AmazonUK AmazonUS |

George Shearing

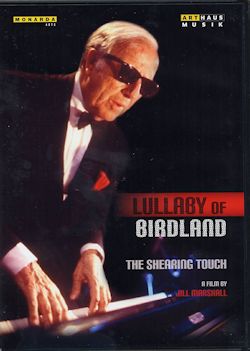

Lullaby of Birdland: The Shearing Touch

Region code: 0 |

Back in the 1940’s, the jazz world, like the rest of the world, was in some turmoil. The end of World War II saw what were, in effect, the end of the big band era and the emergence of “bebop” or just “bop.” When the big bands were no longer economically viable, even when they turned to being bop-centered, they tended to shrink to small group size. At the same time, “dixieland” (or as some preferred to call it “traditional” jazz), began to enjoy a revival, and these two camps engaged in confrontation between “modernists” and “revivalists,” a battle that raged on for the rest of the forties and beyond.

In the midst of all of this, in 1949 a completely new sound emerged by a quintet led by George Shearing—piano, guitar, vibes, bass, and drums playing the melody in unison by the piano, vibes, and guitar. Drums featured quiet brushwork on snare and cymbals, and bass was played four to the measure. (Unfortunately, no video clip of the original quintet—Margie Hyams (vibes), Chuck Wayne, replaced later by Toots Thielemans (guitar), John Levy (bass), and Denzil Bst (drums) is included, or possibly even exists, but it was trail blazing.) There is, as one can hear, a gentleness to the sound, almost an ethereal quality, and there is space left for improvisations. Indeed, one could actually hum or whistle the melody, unlike in most bebop tunes. The sound caught on, so that by the end of the forties Shearing, not an unknown quantity in the U.K., became even better known, perhaps, in the U.S., to which he had emigrated in 1947.

This “sound” was one Shearing, as he says in this documentary, had sought—one which, unlike most modern jazz which seemed to require a code to appreciate, allowed anyone to access. He goes on to analyze his participation in creating the sound, his so-called “locked-hands” style, with one of his best known pieces of 1949: “September in the Rain.” Then follows a scintillating demonstration of different styles that his best known composition, “Lullaby of Birdland,” lends itself to—the piece as it might have been if composed and played by Bach, Earl Garner, even Chopin. He also discusses his love of Latin music and its complicated rhythms and cross rhythms with “Cuban Fantasy.” All of this is a fitting preamble to his discussion of how limiting the quintet became for him after some twenty-nine years of it. He was starting to play on “autopilot,” which he found utterly bored him. He wanted freshness, an escape, a freedom to explore, and not to be boxed in. What follows is a superb demonstration of “Night and Day” played in the style of Beethoven.

As well as the musical content, we also get a glimpse of the personal side with his second wife, Ellie Geffert, a classical singer, and learn how they—or at least she—remembers the start of their relationship. We see the two of them taking walks together or pedaling along on a tandem in England, to which he repaired each fall—one can take the boy out of the country, but not the country out of the boy. While he became a U.S. citizen, he never became an American; yet he did receive recognition for his artistic contribution from his patria, a year or two after the making of this documentary film, in the form of an OBE award in 1996 and a knighthood in 2007.

Born blind in 1919 in Battersea, London, into a totally non-musical working class family—his mother a train cleaner, his father a coalman—Shearing was from the start fascinated by sound. After his mother bought an old piano, the die was cast. From playing in a London pub to playing at Carnegie Hall, Shearing did it all before dying of heart failure at the age of 91 in New York. In the short space of 50 mins., this film helps one understand how this remarkable genius made that journey.

Bert Thompson