BUY NOW AmazonUK AmazonUS |

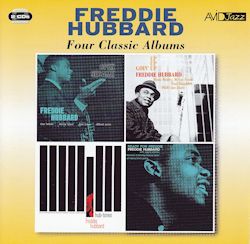

FREDDIE HUBBARD Four Classic Albums

|

CD1

Freddie Hubbard – Open Sesame

Open Sesame

But Beautiful

Gypsy Blues-inspired

All Or Nothing At All

One Mint Julip

Hub's Nub

Freddie Hubbard – Goin' Up

Asiatic Raes

The Changing Scene

Karioka

A Peck A Sec

I Wished I Knew

Blues For Brenda

Freddie Hubbard - Trumpet

Tina Brooks - Tenor Sax (tracks 1-6)

Hank Mobley - Tenor Sax (tracks 7-12)

McCoy Tyner - Piano

Sam Jones - Bass (tracks 1-6)

Paul Chambers - Bass (tracks 7-12)

Clifford Jarvis - Drums (tracks 1-6)

Philly Joe Jones - Drums (tracks 7-12)

CD2

Freddie Hubbard - Hub - Tones

You're My Everything

Prophet Jennings

Hub-Tones

Lament For Booker

For Spee's Sake

Freddie Hubbard - Ready For Freddie

Arietis

Weaver Of Dreams

Marie Antoinette

Birdlike

Crisis

Freddie Hubbard - Trumpet

James Spaulding - Alto sax, flute (tracks 1-5)

Wayne Shorter - Tenor sax (tracks 6-10)

Bernard McKinney - Euphonium (tracks 6-10)

Herbie Hancock - Piano (tracks 1-5)

McCoy Tyner - Piano (tracks 6-10)

Reginald Workman - Bass (tracks 1-5)

Art Davis - Bass (tracks 6-10)

Clifford Jarvis - Drums (tracks 1-5)

Elvin Jones - Drums (tracks 6-10)

Back in the days before I disposed of my collection of jazz on vinyl (prematurely, it is now clear), one of my favourite recordings was a Blue Note LP entitled Hub-Tones. What a pleasure, then, to find it present in this Avid set of four classic albums by the trumpeter Freddie Hubbard. The Hub-tones disc even managed to meet the famously exacting standards of the poet and erstwhile jazz critic, Philip Larkin. Hubbard's arrival on the New York jazz scene of the late 1950s/early 60s, while still only 21 or so, was spectacular in its impact. These four albums, all with Freddie as leader, were recorded over a two year period from June 1960 to October 1962. There is a cohort of sterling musicians to keep him company, not all of them remembered as much as they might be (for example, tenorist Tina Brooks, alto player and flautist James Spaulding and bassist Art Davis). These early recordings show why Hubbard's career took off and why he went on to play on hundreds of discs with just about anyone who mattered in jazz on the East Coast. His work with Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers and with Herbie Hancock was especially appreciated, and also his contribution to the Eric Dolphy Out To Lunch session for Blue Note. Sadly, his career was substantially curtailed, from late 1992 onwards, because of an injury to his lip. Thereafter, his recording dates and live performances were much fewer in number. His last concert was in 2008, as what was to be his final album was released (he died in late December of that year, of a heart attack).

Open Sesame was Hubbard's first disc as a leader and was regarded as a revelation at the time. For me, the ballad But Beautiful is a standout among the tracks. A dreamy and tender Freddie has Tina Brooks on tenor in empathetic attendance. Brooks treats us to a lyrical solo, in a smoochy manner à la Ben Webster or perhaps Lester Young. Gypsy Blue isn't far behind. A Brooks original, it's a number which brings out the best in the group members, all of whom get their share in the spotlight. I recall the sharp distinction which used to be made between West Coast and East Coast jazz, usually to the detriment of the former. Yet, in Hub's Nub, the sound, feel and general liveliness could easily have emanated from California. The standard, All Or Nothing At All, is another winner, in pace and delivery far from the usual languid treatment of the tune. The second album, Goin' Up, dates from November 1960 and features, alongside Freddie, tenor player Hank Mobley, as well as a rhythm section made in heaven, consisting of Tyner, Chambers and Philly Joe Jones. Mobley gives a charged performance of impressive range on his own composition, The Changing Scene, while Hubbard applies himself equally creatively. Philly Joe Jones demonstrates his characteristic dexterity, too. OnAsiatic Raes, a Kenny Dorham piece, aka Lotus Blossom, Paul Chambers produces an absolutely singing bass solo. My favourite, though, has to be Billy Smith's evocative ballad (Smith, a tenor sax player, was a friend of Hubbard's) I Wished I Knew. Mobley shows his excellence with this kind of material and Freddie's moody solo is exquisite. In fact, there's a strong showing all round on an album with probably only one weak link (A Peck A Sec).

Then, there's the Hub-Tones outing. Herbie Hancock is on board this time as part of another admirable rhythm section. James Spaulding complements Hubbard on alto sax and flute. Even the least successful track on the album, For Spee's Sake, is above par. From the opening flourish of the standardYou're My Everything, through the stylish Prophet Jennings (a New York painter of the day) to the vital and urgent title-track and the moving Lament For Booker, we are in the realm of true quality. These are musicians of calibre. Hubbard's vitality and technique on the more up-tempo tracks and his soulful sensitivity on slower numbers illustrate the range of which he was capable. I was impressed by Spaulding's work on flute in particular and by the 22 year old Herbie Hancock, on the threshold of a golden career. Add to that, the drive of Clifford Jarvis on drums and Reginald Workman's quietly effective bass, and you have a potent mixture.

Neither was there anything lacking in the line-up for the Ready For Freddie album, recorded the previous year. This time, Wayne Shorter played tenor sax and, unusually, Bernard McKinney played euphonium, by no means detrimental to the group sound. Aretis and Weaver Of Dreams are the pick of the tracks, the latter showing once more Hubbard's winning way with a ballad. Wayne Shorter is on robust form, especially on Marie Antoinette, his own composition. Crisis, a piece by Hubbard, written with the threat of nuclear war in mind, manages to incorporate strains of hope into a sombre theme. The entire group are on form here with a particular treat being Elvin Jones' solo. There are highlights of individual performance at various points throughout Ready For Freddie, however.

Freddie Hubbard, though widely appreciated, had his critics, too, during his career, especially during his search for commercial success in, say, the late '70s. His legacy has been overwhelmingly positive, for all that. He was credited as influencing Wynton Marsalis and Randy Brecker, to name but two, and was a leading light of his generation, a fine practitioner of the hard bop tradition. These albums remind us of his versatility, fluency and imagination.

James Poore