BUY NOW AmazonUK AmazonUS |

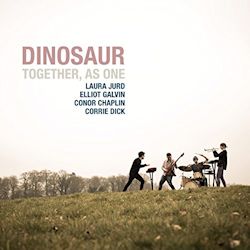

Dinosaur Together as One

|

1. Awakening

2. Robin

3. Living, Breathing

4. Underdog

5. Steadily Sinking

6. Extinct

7. Primordial

8. Interlude

Laura Jurd: trumpet & synth

Elliot Galvin: fender rhodes, hammond organ

Conor Chaplin: electric bass

Corrie Dick: drums

A Radio 3 ‘new generation artist’, by now well-established on the British jazz scene, trumpeter Laura Jurd has been heard to great effect on several recordings in the past year. Huw V. Williams’s underrated Hon deserves special mention, but more attention has been given to, and praise lavished on, Together as One, Jurd’s first album as leader of the quartet ‘Dinosaur’. Critics seem, perhaps inevitably, to refer to Miles Davis in contextualising Jurd’s music. The opening track ‘Awakening’ sounds particularly Milesian. But this is not the electric Miles of ‘In a Silent Way’, for this music is too edgy and melodically various for that. And neither is this the Miles of On the Corner or Agharta - the much-maligned albums that have been revisited and re-assessed in recent years - for the pastel shades and folk lyricism of Dinosaur’s compositions are quite different to the guitar-dominated, ‘scorched-earth’ sound of mid 70s Miles Davis. Jurd seems to draw an a less visited period of Davis’s career: the electric tracks on Filles de Kilmanjaro, the moment where the great acoustic group of the mid-sixties was breaking up, and the tectonic plates of Davis’s music were shifting again with the emergence of his electronic period.

Together, as One shares the exploratory nature of late sixties Miles. A deep, knowledgeable jazz sensibility is infused with the rhythmic influences of rock, and the loops and quirky effects made possible by electronica. Yet, it is clearly quite different to be making this kind of music in 2016 than it was in 1968. Indeed there is something nostalgically quaint about the best tracks on this album. If Dinosaur don’t quite hark back to the Jurassic period, there are shades here of 1980s electronica, 70s disco and 60s psychedelia. What makes it distinctive, and of our era, is the way in which these influences combine - sometimes in fusion, and sometimes in stark juxtaposition.

There are times when this eclecticism becomes tiring. ‘Living, Breathing’ for example is built on an annoying melodic loop. The trumpet’s long notes are played over the, always busy, drumming of Corrie Dick, before the track breaks out into a slightly manic folk melody. To my ear there’s something distinctly English about this kind of jazz, characterised by a deliberate search for quirkiness. It is reminiscent of one strain in the music ofLoose Tubes, the musical equivalent of the montage scenes in Monty Python’s Flying Circus, and is literally miles away from the late 60s music of Black America. This isn’t necessarily a criticism, but perhaps indicates the limitations of the Milesian frame in which Jurd’s music has often been placed.

Indeed, while Jurd can certainly evoke the sound and approach of Miles Davis, she has a very wide palette of sounds on trumpet. She can whisper with Arve Henriksen-esque huskiness, and open up into a broad brassiness evocative of Freddie Hubbard. The music requires this sonic variety, for Jurd is the dominant voice throughout. She is rarely off-stage, and there were times when I yearned for an organ or bass solo (or sax or lead guitar were they available). Conor Chaplin on electric bass and Elliot Galvin on Fender Rhodes and Hammond organ are primarily involved in laying down the rhythmically complex canvasses on which Jurd paints with her wide palette of sounds. The band seem to be on a permanent search for variety, with the trumpet emitting a range of voices over continual shifts in metres and moods, both within and between tracks. This is certainly part of the album’s appeal. But at times, variety can itself become somewhat monotonous.

Daniel G. Williams