Part I [07:15]

Part II [09:49]

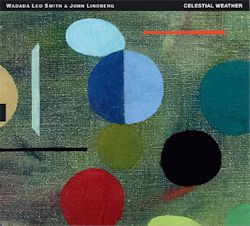

Celestial Weather Suite

Cyclone [05:27]

Hurricane [07:20]

Icy Fog [08:19]

Typhoon [03:31]

Tornado [09:20]

Feathers and Earth

Part I [07:15]

Part II [04:05]

Wadada Leo Smith (trumpet)

John Lindberg (bass)

rec Sear Sound Studios, new York City, June 16 2012

Wadada Leo Smith, now in his seventies (he was born in December 1941) remains one of the most creative figures in jazz. Primarily a trumpeter (in whose

work one hears the whole jazz tradition of that instrument, from Louis Armstrong to Miles Davis and Don Cherry), he is also a composer, whose work extends

beyond the jazz tradition (as in his chamber music, such as the string quartets and other pieces included on a disc in the Composer Portrait Series

(Cambria 8809) played by Southwest Chamber Music), a music theorist (notably in his innovative concept of jazz and world music, which he calls

‘Ankhrasmation’, for which he has invented a new notational system) and a teacher (at various times he has taught at the University of New Haven, Bard

College and The California Institute of the Arts, amongst others). Smith was born in Leland in the Mississippi delta, very much blues country. Indeed his

stepfather, guitarist Little Bill Wallace, led a blues band with which the young Smith played regularly. Smith later played in a great many different

contexts; by the second half of the 1960s he was in Chicago, working with many of the members of the AACM (The Association for the Advancement of Creative

Musicians) while earning a living by gigging on the city’s healthy R & B scene with band such as that led by Little Milton Campbell. Thereafter he

played and recorded with many luminaries of the avant-garde jazz world, including quite a number who, like him, came to musical maturity in the AACM in

Chicago, such as Anthony Braxton, Muhal Richard Abrams, Leroy Jenkins, Roscoe Mitchell, Lester Bowie, Oliver Lake and Joseph Jarman, as well as with

European musicians such as Misha Mengelberg, Han Bennink and Derek Bailey and Japanese figures such as Kazuoko Shiraishi and Kazutaki Umezo. He has given

concerts in collaboration with Persian and Turkish ensembles as well as with western classical ensembles. Amongst such diversity, one strikingly constant

thread has been his fondness for playing in duo/duet combinations. High-spots of Smith’s recorded canon include duets with the pianist Angelo Sanchez ( Twine Forest, Clean Feed, recorded 2013), with the drummers Ed Blackwell (The Blue Mountain’s Sun Drummer, Kabell, recorded 1963, issued

2010), Jack De Johnette (America, Tzadik, recorded 2008, issued 2009) and Louis Moholo-Moholo (Ancestors, Tum Records, recorded 2011,

released 2012). There are many other such recordings in Smith’s discography. In some cases, Smith’s duets (such as the present one with John Lindberg and

the recently issued duet with pianist Vijay Ijer, A cosmic rhythm with each stroke, ECM 2486) are built on long-standing relationships

with musicians he has worked with for many years; sometimes they are collaborations with musician with whom Smith has previously played only rarely (as in

the previously mentioned duet with Louis Moholo-Moholo). Smith obviously finds the duo a particularly interesting format to work in.

Although a generation younger (he was born in Detroit in 1959), bassist John Lindberg has matured musically in many of the same musical environments. He

too played regularly in groups led by Anthony Braxton. He is perhaps still best-known for his work with the String Trio of New York, with guitarist James

Emery and, initially, violinist Billy Bang (who was later succeeded by a number of other violinists), beginning in 1977. But he has played in numerous

other contexts too – with Sunny Murray and Jimmy Lyons, for example. Since 2005 has been a regular member of various ensembles led by Wadada Leo Smith,

such as the ‘Great Lake Quartet’, the ‘Golden Quartet’, and the Silver Orchestra. Reciprocally, Smith has often appeared or recorded as a member of groups

led by Lindberg, notably as part of the quartet which recorded The Catbird Sings (for Black Saint) in 1999 – some of Smith’s solos here are

amongst his best recorded work. Lindberg and Smith are, that is to say, very familiar with one another’s musical temperaments, ideas and practices. They

have often performed as a duo, though this is their first recording as such.

In beginning this review with a lengthy account of Smith, I do not mean to imply that he is the dominant figure here, with Lindberg as his ‘accompanist’.

Naturally there are passages in which one or other of the instruments ‘leads’ or is in some way ‘foregrounded’. But what is remarkable is how many more

(and longer) passages there are when one feels that one is listening to the sound of a single extraordinary instrument, whose registers include both brass

and string sounds, perhaps like some unique Aeolian Harp which can articulate the movements of the air in both such registers simultaneously. This is a

measure of how completely transcend any sense of distinct, ‘competitive’ or even ‘complementary’, consciousnesses and create the powerful illusion of a

single creative mind.

All through his career much of what is best in Smith’s music has been characterised by a kind of inner core of calmness and peace. His ‘free’ jazz, though

often somewhat ‘spiritual’, is almost wholly without the fiercely intense energy of a Coltrane or an Ayler (or even a Braxton). Smith’s natural idiom is

essentially lyrical and, like a lot of the musicians associated with the AACM, he places a very positive value on silence – in the shared belief that, as

John Litweiler (in The Freedom Principle, 1984) puts it – “Music is the tension of sounds in the free space of silence; sounds and silence are

potentially equal elements in the creation of musical line”. Writing more specifically of Smith, Litweiler (ibid) observes that “the calm tension

of sound and silence is a force of water, like the drops of water that become a trickle, then a stream, and eventually alter the landscape”. The metaphors

and analogies that I and Litweiler are drawn to in the effort to characterise Smith’s music make it clear, I hope, just how ‘organic’ his music is. I use

‘organic’ here in terms of the contrast made by Coleridge, the poet-philosopher of Romanticism: “the form is mechanic when on any given material we impress

a predetermined form, not necessarily arising out of the properties of the material -as when to a mass of wet clay we give whatever shape we wish it to

retain when hardened. The organic form, on the other hand, is innate; it shapes as it develops itself from within, and the fullness of its development is

one and the same with the perfection of its outward form”.

Such considerations seem especially apt in relation to the central work on this disc – the five part sequence ‘The Celestial Weather Suite’. (It may be

pertinent to note that Smith refers to Lindberg as a “naturalist – a man of the mountains, national parks and rivers of America”). Despite titles such as

‘Cyclone’, ‘Hurricane’, ‘Typhoon’ and ‘Tornado’, the ‘Celestial Weather Suite’ is not music of wildness and storm. It is as if these phenomena are being

invoked, not in terms of their ferocity or impact, but rather in terms of the beauty (if studied with detachment) of their ‘patterns’, the changing schemes

and structures of energy and movement they write on (and in) the air. The result is beautiful music which is simultaneously intimate and sublime. The CD

booklet tells us that these pieces were “spontaneously improvised” and “named for different weather phenomena”. They could certainly not have “developed”

such a perfection of outward form” (to quote Coleridge once more) without the mutual (organic?) interdependence of Smith’s and Lindberg’s musical

intelligences. These pieces do not ‘paint’ or even ‘evoke’ in any explicit way the phenomena in their titles; rather, such titles recognise the fact that

the music made by Smith and Lindberg, and the audible processes of its making, have things in common with, share underlying patterns with, such “weather

phenomena”.

In the memorial tribute to AACM bassist Malachi Favors (credited to Smith) and in the two part ‘Feathers and Earth’ (credited to Lindberg) the music is,

surely, made up of both written and improvised elements (though where exactly one ends and the other begins isn’t necessarily always evident to the ear

alone).

This review has grown rather long. Let me close it briefly, by observing, to anyone who has read this far, that I have, quite simply, found this music more

fascinating, beautiful and rewarding than pretty well any other newly recorded jazz I have listened to in (say) the last ten years. This disc has scarcely

been out of my CD player since the first time I put it in. Even if ‘free’ jazz is not something you would usually choose to listen to, I urge you to try to

hear this.

Glyn Pursglove