Hindustan

Shreveport Stomp

Tres Moutarde

Martiniqu

Milenberg Joys

Flow Gently, Sweet Afton

Hot Lips

Are You From Dixie?

Madagascar

Juba Dance

Toll Gate Blues

Wrought Iron Rag

Big Fine Girl

It's All Right With Me

Begin the Beguine

Beale Street Blues

Muskrat Ramble

Panama

Madeira

Banjolie

Waiting for the Robert E. Lee

Frankie and Johnny

Colonel Bogey's March

Watching Dreams Go By

Hesitatin' Blues

That's a Plenty

Change O'Key Boogie

Mack the Knife

Creole Love Call

Tell 'Em 'Bout Me

When My Sugar Walks Down the Street

Twelfth Street Rag

Blues Ingee

Shim-Me-Sha-Wabble

St. Louis Blues

How Ya Gonna Keep 'Em Down On the Farm?

Just a Closer Walk With Thee

Royal Garden Blues

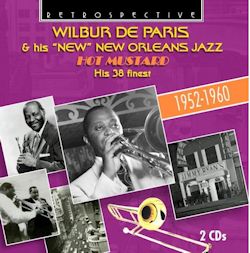

Wilbur De Paris and His ‘New’ New Orleans Jazz Band

Recorded 1952-60

RETROSPECTIVE RTS 4259

[78:20 + 79:31]

You can’t really go wrong with Wilder De Paris. This twofer, in the well-selected Retrospective line, charts his band’s course from 1952 to 1960 and the

first thing that hits the listener is the confidence and brio of the ensemble. Certainly there’s a sometimes relentless rhythm to the earlier tracks, where

Wilbur’s far better soloistic brother, Sidney, is forced into a brash on-the-beat lead. Even Omer Simeon, veteran of Jelly Roll Morton’s band in the 1920s,

sounds uncomfortable at the hell-for-leather tempi and arrangements. Don Kirkpatrick was a good band pianist but his interjections fail to calm the hectic

nature of the music-making. But once things hit the mid-50s and Doc Cheatham intermittently joins Sidney for the front line trumpet chores, things are more

consistently fine and varied. In truth one can appreciate the embryo of that development in Martinique from 1952 where Sidney’s muted wa-wa solo

is tight, taut and gleaming, if brief. It’s in the varied arrangements, though, that one senses the developments to come.

This extended to selection of tunes. You wouldn’t think Flow Gently, Sweet Afton, an evergreen from 1837, would work but curiously it does.

Because some of the band were versatile – in addition to Cheatham reinforcing the trumpet line, Sidney De Paris also plays tuba - the texture of the

ensemble could be thickened and deepened to benefit. The live Boston concert of October 1956 shows what the band could do when it stretched out, and the

sense of communicative vitality is visceral here, not least in the long, slow Toll Gate Blues. It’s good to hear Jimmy Witherspoon join the band,

albeit not for long, in the two-minute Big Fine Girl. Though he was not an imaginative soloist, Wilbur knew how to get the most out of

arrangements and band colours and this is the most intriguing thing about his band. Asking drummer Wilbert Kirk to play harmonica, the leader himself

employed the valve trombone and got Omer Simeon to dust down his alto sax, the last mentioned being a decidedly good move in the case of Muskrat Ramble.

Of course there were elements of corn – notably banjo-corn - in the band’s aesthetic but with such a quixotic tune book (Colonel Bogey, anyone?)

there’s no time to pick hairs. The band trips lighter the later we get, and by 1959 with the rhythm section established as pianist Sonny White, guitarist

John Smith, veteran bassist Hayes Alvis and drummer Kirk, a good time is had by all. In the last year of this survey Garvin Bushell replaced Simeon who’d

died of throat cancer in 1959 – though he was playing almost to the end. Bushell had a few bizarre doubles up his sleeve – bassoon and piccolo - so he

continued the one-man-band ethos adding even more layers of colour.

This was an influential band, too: wide ensemble colours, doubling a-plenty, often weird tune choices, catholic approach to Morton, blues, popular song,

gospel, 1920s archaeology, late Edwardiana. It must have been immensely influential on Chris Barber, for instance.

As for the transfers I’m happy to report that they are better than those on OLP #15 (222980-203) which contains eleven of the same tracks, and

Retrospective’s are transferred at a higher level too. Good notes complete this eminently fine release.

Jonathan Woolf