CD1

1. Oleo

2. Untitled Original

3. Doxy/Love Walked In

4. Dearly Beloved

5. Doxy

CD2

1. Solitude

2. Oleo

3. St Thomas

4. Home Sweet Home

CD3

1. Lover

2. Unidentified Ballad/Alexander’s Ragtime Band/Home Sweet Home

3. Dearly Beloved

4. Oleo

CD4

1. Untitled Original

2. Tempus Fugit

3. Untitled Original

CD5

1. Untitled Original

2. Untitled Original

3. Untitled Original

CD6

1. Oleo

2. Three Little Words

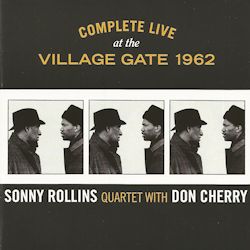

Sonny Rollins – Tenor sax

Don Cherry – Cornet

Bob Cranshaw – Bass

Billy Higgins - Drums

“Don Cherry and I would practise together, just he and I. Great fun. He had a fantastic musical imagination, musical mind. He always kept things on a

creative, unplanned level. Spontaneous.”

Thus Sonny Rollins described the sessions where he and Don Cherry got together informally to try out various things. This six-CD boxed set from 1962

contains the first recordings of that pairing, backed by bassist Bob Cranshaw and drummer Billy Higgins. Rollins had recently returned from his three-year

sabbatical and more recently had recorded the albums The Bridge and What’s New, both with guitarist Jim Hall alongside him. But Don

Cherry partnered Sonny on several more recordings, although their last recording together came in the following year, 1963, for a compilation album called Three in Jazz.

Although Rollins found Cherry a useful team-mate to spark off, Cherry’s contributions on these six CDs often seem irrelevant to what Rollins is playing.

His cornet flutters and shrieks in the background behind Rollins’ more muscular solos, while Don’s own solos follow a more free-form style which lacked the

melodic foundation of Sonny’s improvisations. Rollins tends to take a tune – often one which few other jazzmen have essayed – and uses it as the

starting-point for his solos. Although these may wander a long distance from the base, they somehow still maintain a connection with the original. Don

Cherry’s playing, on the other hand, exemplifies what has come to be called “free improv”: extemporization which has no firm basis at all but simply

produces what the musician feels like playing from moment to moment. Ideally this should bear some reference to what the three other musicians are playing

but this is sadly not always the case. As the well-known Penguin Guide to Jazz said, “hardly anything the two men play bears any relation to the

other’s music: recorded live, they might as well be on separate stages.”

Admittedly this sort of free playing was being explored at the same time by such people as Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler and John Coltrane – and is still

being explored today – but it strikes me essentially as a dead end. Music has traditionally consisted of three elements: melody, harmony and rhythm.

Subtract the melody and you are floating in perilous waters. Free improvisation may work if the musicians listen to one another and somehow respond to one

another, instead of simply playing a series of unconnected phrases. In the case of free improv, this has often degenerated into a series of jagged notes or

other seemingly random sounds.

One place where the two frontmen seem to work together is Solitude, where Don Cherry plays several phrases that suggest the tune but Sonny Rollins

only seems to pick it up after a few minutes and then diverges in different directions for a while before stating parts of the melody clearly. Billy

Higgins is (literally) instrumental in determining some directions in which the track develops, suggesting a marching beat and other possible rhythms. Bob

Cranshaw may be a somewhat prosaic bass player but he can at least lay down a vigorous beat for the fast bebobbish tunes. The rhythm section’s important

role is illustrated by the first version of Dearly Beloved. At one point, they leave Rollins free as he slows down the tempo; then they join in

while Sonny plays a march and goes into double tempo for a frantic rush before a bombastic ending with everyone playing in magisterial mode.

Other particularly interesting tracks include Lover, a tune seldom heard from Sonny but full of intriguing twists and turns, and the four versions

of Rollins’ own composition Oleo. Listeners may regard the latter as too much of a mixed bag but they contain many worthwhile passages. There is

also interest in the two versions of Doxy. In the first, it is fascinating to note how quickly Rollins changes the Doxy theme into Love Walked In. In the second Doxy, the coda is typical Rollins, with an ending extended into a supplementary piece of lyricism.

Under the influence of Don Cherry, Rollins is often tempted down the road of free improvisation but, being Sonny, there is enough melody in his solos to

excuse the ventures into honks and squeaks. The melodiousness is often encapsulated in brief quotations from popular songs – everything from I’m Beginning to See the Light to the Funeral March and Come to the Cookhouse Door. I wish I thought that some of Don Cherry’s odd sounds

were deliberate instead of being unwanted fluffs.

The experimentation with Don Cherry gave Rollins an awareness of how he could take a melody and shape it in surprising new ways without losing the many

threads (and the audience!). That is the mark of Sonny’s later, mature work, which he pursues today with equal artistic success.

This set of six CDs, packaged in a sturdy cardboard box, contains many moments of well-recorded beauty and surprise as well as plenty of noodling which,

frankly, doesn’t work very well. But like all Sonny’s work, it presents the listener with some daring music from a great creator.

Tony Augarde

www.augardebooks.co.uk