High How the Moon (Wilder’s Moon)

I Think Of You with Every Breath I Take

Cherokee

Prelude to a Kiss

My Heart Stood Still

Six Bit Blues

Mad About the Boy

Darn That Dream

The World Is Waiting For the Sunrise

There Will Never Be Another You

Moonlight in Vermont

I Can’t Believe That You’re In Love With Me

Used Blues

Tea For Two

Delta Blues

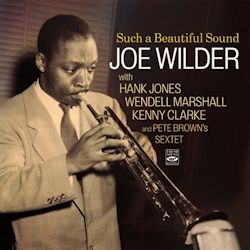

Joe Wilder (trumpet): Hank Jones (piano): Wendell Marshall (bass): Kenny Clarke (drums), recorded November 1955 (tracks 1-8)

Pete Brown Sextet: Joe Wilder (trumpet): Pete Brown (alto sax): Wade Legge (piano): Wally Richardson (guitar): Gene Ramey (bass): Rudy Collins (drums),

recorded November 1954 (tracks 9-15) [79:21]

Inevitably greater poignancy clings to this release given trumpeter Joe Wilder’s recent death. Elegant, lyrical, Wilder – born in 1922 – graces everything

he plays with warmth, and his metier was relaxed fluency. The first eight tracks were recorded in 1955-56 by what was the Savoy house band – Hank Jones,

Wendell Marshall, and Kenny Clarke – with Wilder the addition, though nominal leadership varied between Wilder and Jones. Wilder leads the quartet with a

series of pliant and imaginative solos, the lower spectrum of his register being most apparent in Six Bit Blues, taken slowly. Jones evokes Tatum

at points, in Prelude to a Kiss most overtly, and in a superficially unlikely vehicle like Noel Coward’s Mad About the Boy, the band’s

cosmopolitan professionalism sees it through.

There is nothing austere about Wilder’s performances, and he meshes well with that elegant and swinging trio. But with the 1954 date, with a wholly

different personnel, another kind of feel is generated. Wade Legge was Dizzy Gillespie’s pianist, and Pete Brown an accomplished exponent of jump alto and

they lend their skills to the seven-track date. Brown is typically upfront and bustling on I Can’t Believe That You’re In Love With Me and he

sounds like he is squeezing the blues out of his horn on Used Blues. Guitarist Wally Richardson takes a decent solo or two and Wilder is his

elegant, imperturbable self. This is something that has often counted against him critically speaking and for those reared on the heat and thrust of, say,

Buck Clayton or Roy Eldridge, Wilder’s altogether more genial playing can sound withdrawn, non-committal or even bloodless. But that would be to

underestimate what Wilder was trying to achieve. He was at his best in ballads, where his lovely tone shone brightly and sensitively, and there are a

number of examples in this well transferred and annotated disc that attest to the fact.

Jonathan Woolf