1. Lunfardo

2. Muerte del Angel

3. Resurrección del Angel

4. Tristeza de un Doble A

5. Adiós Nonino

6. Chin Chin

7. Otoño Porteño

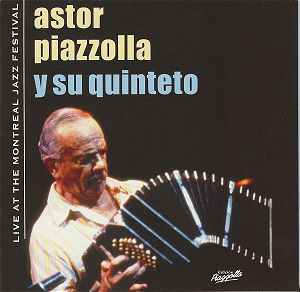

Astor Piazzolla – Bandoneón

Pablo Ziegler – Piano

Fernando Suárez Paz – Violin

Oscar López Ruiz – Electric guitar

Héctor Console – Double bass

A few days ago I reviewed

the Sydney Symphony Orchestra's Kaleidoscope

performance, subtitled "Latin American

Nights" and including Piazzolla's Concerto

for Orchestra and Bandoneón. I felt

drawn in that review to refer to the performance

of the Latin genre as 'ferocious' and when

considering this particular review, I again

find myself back there, not only for its self-reflexive

sound (Say it out loud. Ferocious -

it sounds like the wind roaring!) but for

the way that it indicates not only a constant

passion, but also a biting impact. The same

passion an actor draws upon when shouting

'Mambo' in Bernstein's West Side Story.

The passion of bebop in a club, cranked to

a level where the beginnings of the notes

burn a little. Piazzolla's music hits you

hard, no matter which way you look at it.

This is one of the many reasons he is affectionately

referred to as The Great Astor in his

home country. He is the heart of the new tango,

especially from an outside/European perspective.

To be slightly unorthodox,

I would like to start with the penultimate

piece, Chin Chin, and then move to

the piece right before that, Adios Nonino.

The reason behind this is because they are

the standout performances on this album. Not

purely for technical reasons, but because

of the way they encapsulate both the elements

of live improvised jazz and the tango traditions

Piazzolla comes from. The other tracks may

be perhaps seen as supporting members of a

cast of free-roaming beasts.

Chin Chin illustrates

the idea of ferocity, especially in a small

ensemble sense, showing that it is not sheer

polyphony which draws me towards this adjective,

but that it is, instead, the nature of the

piece itself and how it fits into the genre.

The performance begins with a few bars of

the fragmentary bandoneón melody before

being joined by sporadic percussion, piano

glissandos, incensed electric guitar and atonal

violin slides. It plays itself out in true

jazz form, with the instruments given space

to solo amongst the seemingly haphazard accompaniment

and then brought back into the recapitulating

head. The ferocious nature of the piece that

I refer to is best reflected in the open piano

solo which drifts further and further away

from the ensemble, growing in intensity and

beautiful chaos. Pablo Ziegler’s performance

is inspiring and obviously inspired, his inventions

never seem old or retired, constantly shifting

and thickening into an intimidating cacophony.

Then suddenly, with ease, he brings back the

tango rhythms, precise and full of intention

to round out the piece. Piazzolla’s greatest

strength in this piece is his ability to showcase

another musician. The melody begins with a

bandoneón focus and grows from that,

but the chaos draws us towards the piano.

A brilliant performance and a nice departure

from the traditional quintet showcase.

Adios Nonino is partly

well known for the history behind its composition.

The story goes that Piazzolla heard of his

father's passing and retreated to his room

in silence. After half an hour, from within

the room came the melancholy melody which

Adios Nonino begins with. But do not

mistake this story for one that leads to a

simple or pure nostalgia. This performance

in particular begins with an open piano solo

by Ziegler, which at times verges on the melancholy,

but it is far from simple. Rather, it draws

upon Piazzolla's melody, adding beautiful

and grandiose ornamentation. After almost

two and a half minutes, Piazzolla enters on

the bandoneón playing the opening line

to the melody, cleverly composed to finish

unresolved. As he holds the final note, the

suspense builds, holding steady and waiting

for the resolution. But where melancholy would

ordinarily take over to pour out the grief

Piazzolla must've felt after his father died,

the strings enter: heavy and raucous. A heavy

calculated stumbling that drives forward only

to hit you with yet another melancholy melody,

this time on solo violin. Perhaps this is

truly what Piazzolla wanted to hint at with

Adios Nonino, the manic nature of mourning

and the abrupt coming of death. But the melancholy

violin is not alone for long; it finds a communal

longing with the bandoneón. This solo

section is heart-wrenching; the shrill violin

draws you into a brittle grief that swirls

and lifts, uncertain but unmistakably emotionally

driven.

The rest of this recording

contributes to a collection of Piazzolla’s

better known pieces, including Muerte del

Angel and Resurrección del Angel.

These two pieces act as a nod towards a more

traditional arrangement, most probably because

of the nature of their composition, as part

of Piazzolla’s ‘Angel Suite.’ Muerte del

Angel (Death of the Angel) takes on the

sound of a traditional tango and the heavy

rhythmic motifs that are associated with the

genre, while Resurrecion del Angel

(Resurrection of the Angel) allows for yet

another solo exploration, this time by Fernando

Suarez Paz on violin. Also, this is possibly

one of the few pieces on the album that explores

the smooth chordal possibilities of the bandoneón.

This performance recording

is a wonderful introduction to the work of

Astor Piazzolla and the nuevo tango.

The recording itself is of an extremely high

quality, retains the atmosphere of a live

performance and the dynamic nuances that such

a situation brings forth. Not only was Piazzolla

in fine form, his quintet exceeds all expectations;

they are rhythmically and stylistically ‘in

tune’ with the genre and Piazzolla’s composition

from beginning to end. Live at the Montreal

Jazz Festival is a wonderful addition

to the record collection of both jazz and

classical fans.

Sam Webster