Juba Juba

Back Home

Stay With Me

In The Evening

Woodward Avenue

Eastern Market

Russell and Eliot

Buddy and Lou

Nocturne

Live Humble

A Long Time Ago

Nubian Lady

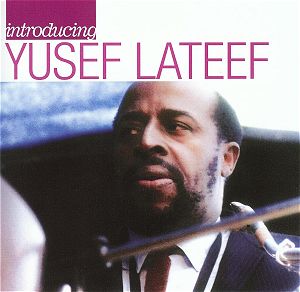

Yusef Lateef (born William

Evans or William Huddleston, I’ve seen both

surnames mentioned, in 1925) was a fine, hard-toned

and swinging tenor player who grew up in Detroit.

He joined Dizzy Gillespie’s Big Band in 1949

and was recording as a leader in 1957. A pioneer

of Eastern music he was also a sometime scorner

of the term "jazz" – he refused to be included

in one of the Feather-Gitler Encyclopedias

of Jazz but they included him anyway,

doubtless to his chagrin. Still, he recanted

often enough to announce that his primary

language was, after all, jazz.

But he was still a pioneer

in his musical horizons and in his choice

of instruments. He was an accomplished flautist

and took on a battery of Eastern instruments

as well – Asian reeds, the argol, shennai

and various oboes, as well as percussion instruments.

He enlarged the palette bringing a sense of

quiet rapture to his music.

This is a compilation album,

with minimal notes and discographic information,

which takes some of his best recordings from

the period 1968-72. They’re derived from albums

such as The Blue Yusef Lateef, Yusef Lateef’s

Detroit, Suite 16 and the Diverse Yusef Lateef.

Fortunately we stop before we get to the period

when he was carried away by his excesses and

began quasi-symphonic noodling.

Juba, Juba is strongly

of its time – blues drenched but with some

hokum as well and a rough chorus eventually

formulating the word "Freedom" in politicised

fashion. Lateef had a fondness for Chicago

style harmonica in his band. This and the

next track, Back Home, derive from

The Blue Yusef Lateef and we can hear how

strongly rooted in the tradition is his tenor

playing whilst his flute adopts a rather more

airy and melodic freedom. He was never as

dynamic or unconventional a multi-instrumentalist

as, say, Rahssan Roland Kirk but his improvisations

did carry with them a remote beauty all their

own. Stay with Me for instance is a

lovely song, beautifully played. And his oboe-sounding

In the Evening, that Leroy Carr standby,

is a down home blues that hits home hard.

By the time of Eastern

Market – nothing to do with the cod exotica

of Albert Ketèlbey – we reach a period

of immersion in such affiliations; terrifically

powerful brass accompanying but in the end

let down by some generic wailing. For all

his world music outreach he was, at heart,

a blues player – witness the electric guitar

solo in Russell and Eliot and the easy

lope of Buddy and Lou. He utilised

the Hammond organ as he did, less successfully

in my book, the vogueish clattering of half

digested Eastern percussion. But listen to

the righteous old time blowing on Live

Humble to appreciate that here was a man

versed in the lineage, aware of his heritage,

and not afraid to call his children home.

Jonathan Woolf