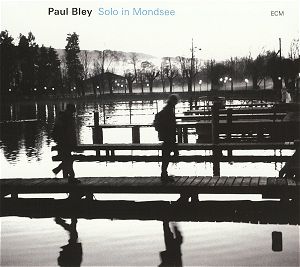

Released in time for Paul Bley’s 75th birthday

in the autumn of 2007, Solo in Mondsee

is the first Bley solo piano album on ECM

in 35 years. Paul Bley was born in Montreal

in 1932. While still in his twenties he played

with Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Coleman

Hawkins, Ben Webster, Chet Baker, and many

others. At 21, he made his first album as

a leader for Charles Mingus’s Debut label,

with Mingus himself on bass and Art Blakey

on drums.

Briefly based in California in the late 1950s,

his quintet of 1958 helped introduce the talents

of Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, Charlie Haden

and Billy Higgins to the jazz world. In the

early 1960s, as a member of the Jimmy Giuffre

Trio and in his own groups, Bley brought chamber

music clarity into the new domain of free

jazz. A prolific recording artist, Bley was

amongst the first artists to appear on ECM

with "Paul Bley with Gary Peacock"

(recorded 1964 and 1968) and "Ballads"

(recorded 1967) – those were issued as ECM

1003 and ECM 1010. In 1972 Eicher recorded

Bley solo on the enduring classic "Open,

To Love" (ECM 1023), to which this new

solo album might be seen as a much belated

sequel.

Manfred Eicher had already recorded András

Schiff playing Schubert fantasies on the superb

Bösendorfer Imperial Grand in Mondsee,

Austria (ECM New Series 1699), and decided

to invite Bley to the same location. The choice

on instrument has to be a big influence on

any improvised session, and the more rounded

sound and greater sustain that a Bösendorfer

has over the usually brighter sounding modern

Steinway suits Bley’s sense of space and timelessness

to the ground. Bley doesn’t overwork the tonsil-rattling

bass that this piano has, but in this superb

recording you can sense him exploring, roaming

the registers and revelling in the instrument’s

expressive potential.

The Mondsee Variations are less variations

in the classical sense – based around a theme

or musical idea, they are more a set of musical

shapes fitting around a mood; filled with

musical surprises and unexpected changes of

direction. If your are hunting for references

to describe Paul Bley’s style then for me

at least, it is a relief not to have to say

he owes anything to Keith Jarrett – the fact

being that the direction of any influence

is the other way around. Bley is best known

for his myriad collaborations and work in

the field of electronic music making, and

I find his solo pianism hard to categorise.

Thinking of some other favourites, he is in

any case far removed from the down-to-earth

brilliance of Dave McKenna, or the more Gallic

romanticism of Michel Petrucciani – yes, if

you like Keith Jarrett, at least at when he’s

not being obscure and pretentious, you should

like this. Bley shares that right-hand melodic

facility which is the magic implement of all

great jazz pianists. The harmonies are sometimes

suggested or lushly present, but they always

feel ‘right’. This is not ‘free jazz’ improvisation

in the sense that it sails in any way close

to aversion-therapy abstract musicianship,

and many tracts of this album could almost

withstand misuse as background music if you

were so inclined, although the higher-number

variations do become a little more demanding.

There isn’t much in the way of overt funkiness:

Paul Bley’s groove lies several layers deeper

than the immediately accessible epidermis,

but seek and ye shall find. Listen properly,

and become acquainted with this pianist’s

individuality of idiom and style, and you

may find that this album’s 55 minutes have

passed in a kind of trance. You won’t get

those 55 minutes back, but time was rarely

spent with greater reward.

Dominy Clements