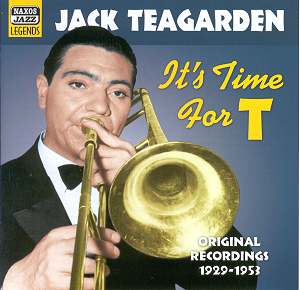

The world is not short of

Teagarden retrospectives – this is in fact

the second in Naxos Jazz Legends’ own series

– but they’re always welcome. If you’ve not

yet racked up the Charleston Chasers sides

or the Big Eight, a stellar meeting with Rex

Stewart, Barney Bigard and Ben Webster in

the front line, you might want to give the

track list a look-over.

If you do you’ll find that

amidst the expect Ben Pollack and Teagarden

and His Band sides you will encounter four

Standard Transcription 78s recorded in Los

Angeles from 1941-45. These were with his

Orchestra, a largely anonymous studio band

without any other soloists of distinction.

His glorious solo in Nobody Knows The

Trouble I've Seen is all too brief

and the tune Glass Blues – credited

to "composer unknown" – will be

better known as The Mooche; a fine

way to avoid royalty payments, despite the

nod toward Ellingtonia.

One of the advantages of

a single disc compilation is to trace Teagarden’s

lineage from the early Jimmy Harrison influence

(noticeable in Dinah) to the effortless

lyricist of the later period. Admirers of

his meeting with Louis Armstrong and Earl

Hines in Knockin’ A Jug will also recognise

his solo in the 1929 Makin’ Friends

– stop time chorus, a touch of Armstrong-influenced

scat and bluesy cornet from Jimmy McPartland

(who once tapped me on the shoulder to let

him through at the 100 Club in London whilst

carrying Bix Beiderbecke’s old chair; "’Scuse

me, son" he said as he passed, a magical

figure reeking of speakeasies and rapacious

brass duels).

Listen out for the Fletcher

Henderson influence on the reed section’s

chorus in Beale Street Blues and for

Joe Venuti’s swing on After You’ve Gone

– and not forgetting Jess Stacy’s evocative

Teddy Wilson-like limpidity on Diane. Lovers

of Pee Wee Russell can admire his Picasso-esque

obbligato to Teagarden’s vocal on Serenade

To A Shylock. The depth of the sidemen

is one of the most obvious pleasures throughout.

Recording quality is good;

a few of the earlier sides are very slightly

noisy but that’s of little account. If you’ve

yet to meet some of these tracks – you can

hardly have avoided all of them unless you’re

mired in specialism of the most arcane kind

- then volume two in Naxos’s series is certainly

worth a listen.

Jonathan Woolf