Black Bottom Stomp [3.10]

Smoke House Blues [3.23]

The Chant [3.07]

Tom Cat Blues (piano solo) [3.00]

King Porter Stomp (piano solo) [2.48]

Sidewalk Blues [3.26]

Dead Man Blues [3.20]

Steamboat Stomp [3.05]

Grandpa’s Spells [2.51]

Original Jelly Roll Blues [3.03]

Doctor Jazz - Stomp [3.03]

The Pearls (piano solo) [2.46]

The Pearls [3.24]

Mr Jelly Lord (Jelly-Roll Morton and his Trio)

[2.50]

Georgia Swing [2.28]

Deep Creek [3.29]

Seattle Hunch (piano solo) [3.06]

Freakish (piano solo) [2.51]

Ponchatrain [2.53]

Burnin’ the Iceberg [3.03]

All numbers written by Ferdinand ‘Jelly-Roll’

Morton except tracks 2 and 9 (Charles Luke),

and 11 (King Oliver-Walter Melrose)

rec. Richmond, Indiana 9

June 1924 (track 4), Chicago 20 April 1926

(tracks 5, 12), 15, 21 September 1926 (tracks

1-3, 6-8), 16 December 1926 (tracks 9-11),

10 June 1927 (tracks 13-14), New York 11 June

1928 (track 15), 6 December 1928 (track 16),

Camden, New Jersey 8 July 1929 (tracks 17-18),

9 July 1929 (track 20), New York 20 March

1930 (track 19)

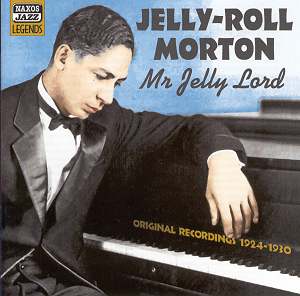

Ferdinand Joseph La Menthe,

aka Jelly-Roll Morton, was a jazz giant and

a performing genius. Born near New Orleans,

the spiritual if not actual birthplace of

jazz, Morton began playing piano at ten, usually

background music for customers in bordellos,

something he had in common with Brahms, who

played in Hamburg’s brothels at a similar

age. There the common thread ends.

Between 1904 and 1922 (aged

19-37) Morton dabbled in a variety of jobs

such as pool shark, vaudeville comedian, pimp,

hotel manager, boxing promoter, tailor and

gambling house manager, with piano playing

a constant throughout. He only began recording

in 1923 at a time when he had already defined

a role for himself in the profession midway

between ragtime and early jazz. By the time

he moved from LA to Chicago in 1923, he was

the complete professional musician and recorded

piano solos for Paramount, though regrettably

they were noted for crude results regarding

such basics as minimising surface noise. Fortunately

he switched to Victor and produced his best

work between 1926 and 1930. After his contract

ended, Morton’s life was not happy. Struggling

with poor health - a weak heart - and indecisive

moves such as running a dive in Washington,

he died in 1941 just as his music was making

a comeback.

These twenty tracks are the

pick of those four golden Victor years 1926-1930,

and the cast list of his fellow performers

makes impressive reading, Kid Ory (trombone),

Johnny St Cyr (banjo), Omer Simeon, Barney

Bigard and the great Johnny Dodds (clarinets),

George Mitchell (cornet), Baby Dodds (drums),

and a host of others who came and went from

the Red Hot Peppers. ‘Ah Mr Jelly’- up goes

the cry from Morton himself during the evocative

Smoke House Blues, a haunting number. So too

is The Pearls, which you get the bonus chance

to hear twice, in its band version immediately

after the solo on tracks 12-13, and which

is really a thinly disguised Beale Street

Blues. Besides stunning piano playing throughout

(there are five piano solo tracks here), it

is Morton’s high level of imaginative and

unpredictable creativity which so impresses.

King Porter Stomp - better known as a big

band classic a year later when Fletcher Henderson

recorded it - contains some strange harmonies

and piano textures, the chords widely spaced

between the two hands. More vaudeville-style

speech introduces tracks 6-8 followed by two

classic blues and a spirited stomp with fabulous

playing all round. That defining December

1926 session in Chicago produced three brilliant

numbers, Grandpa’s Spells, Original Jelly

Roll Blues and Doctor Jazz - the only number

which has a vocal, Morton himself - tracks

9-12. It’s worth buying this disc for these

three tracks alone.

Transfers and digital restoration

by David Lennick and Graham Newton respectively

are excellent, and Scott Yanow’s comprehensive

notes highly informative. I grew up with a

couple of well-worn, oft-played 10 inch LPs

of Jelly, and many of these numbers have remained

fresh in my mind when I hear them all again

on this CD. Morton was a genius, and if he

had not been known to posterity by his nickname,

Doctor Jazz would have been the perfect alternative.

Christopher Fifield