|

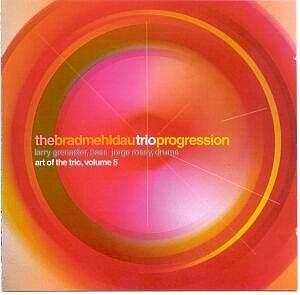

THE BRAD MEHLDAU TRIO

Progression: Art of the Trio, Volume 5

Warner 9362-48005-2

2CD Warner 9362-48005-2

2CD

Amazon

UK

|

The fifth volume of Brad Mehldauís ongoing "Art

of the Trio" series builds on and extends the success of the past

four volumes. This is turning into one of the truly great series of

recordings, with each new volume bringing fresh delights.

Mehldau is again joined by Larry Grenadier on bass

and Jorge Rossy on drums. And it must be emphasised that the series

title is absolutely spot on - this is the art of the trio. Any

successful piano trio (as opposed to just piano plus rhythm section)

relies on a certain mysterious alchemy to make the whole greater than

the sum of its parts, and Grenadier and Rossy are as vital to the creative

process as Mehldau. For example, Grenadierís solo on (the Mehldau original)

"Sublation" is a model of its type - swinging, integrated,

creative and economic. The three have played live together for over

six years, and they do not record material until it has been allowed

to grow and blossom in a live context. On this album (as on AOTT

Volumes 2 and 4) they were again recorded live at the Village Vanguard

in NYC, a venue that seems to bring out the best in them.

Progression is also an apt title for this album;

the trio is developing and progressing with each new release. It is

instructive to compare the version of Nick Drakeís "River Man"

here with the version on the 1998 (studio recorded) album Songs (AOTT

Volume 3). The studio version is a pleasing tiptoe around the melody,

with the occasional embellishment or variation, which fades out before

five minutes have elapsed. This live version is longer and far less

reverential, less self-consciously a cover of a non-standard piece.

(Or is "River Man" on its way to becoming a standard?) It

uses the melody more impressionistically and as a basis for improvisation.

It sounds like what it is - a song that the trio has lived with and

explored for a few years. It is crammed with invention from all three

players, and its eleven minutes flash by. It typifies the trioís music;

Mehldau favours songs Ė from diverse sources (The Meat Puppets?!) -

with strong melodies, being particularly fond of standards. Here, these

include "The more I see you", "It might as well be spring",

"Secret Love" and "Cry me a river". Their melodies

give an accessible way into the trioís music, but Mehldau then uses

them to tell his own stories, taking as much time and going down as

many byways as he feels like. Along the way, Mehldau uses his virtuosity

sparingly, rarely putting on a technical display. However, when he does

let rip, as on the start "Alone Together", it is awesome and

breathtaking. Mostly (mercifully!) the technique is subservient to the

feel and mood of the songs.

Mehldau gets the prize (again!) for the heaviest sleeve

notes of the year. This time, they constitute a philosophical, polemical

and poetical treatise on the relationship between music and language,

which would not disgrace the pages of an academic journal. Mehldau does

not admit much of a role for the humble reviewer: "To speak of

music is a folly, a futile attempt to break through its wordless fortress."

and "Speech-language by comparison [to music] is crippled from

the outset, a waterlogged form of communication." (Like doing a

dance about architecture, eh Brad?) OK, Iím off to consider my career.

John Eyles