TALES OF THE ILL-FATED VICAR

by Charles A. Hooey

Liza Lehmann's opera The Vicar Of Wakefield sprang

to life in London at the Prince of Wales Theatre just prior

to Christmas in 1906. From its early tryout in Manchester to

the final curtain, it lived a mere nine weeks.

Lehmann first delighted music-lovers in 1896

with a charming and unique song cycle, In A Persian Garden,

following with In Memoriam for bass voice and piano

in 1899 and The Daisy Chain in 1900, both fine successes;

then she set her sights on creating a comic opera based on

Oliver Goldsmith's immortal tale. But fate would intervene.

Operas

and musicals try and fail on a regular basis so why is the Vicar so

special? The answer: the music, which was universally acclaimed.

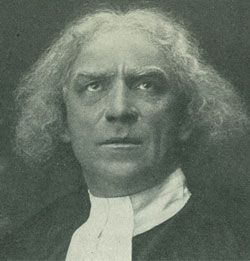

The work's demise stemmed

from a series of miscues as is apparent from the writings of

three participants: composer Lehmann, David Bispham (pictured

as the Vicar), who sang the Vicar, and Edith Clegg, his younger

daughter, Sophia.

Operas

and musicals try and fail on a regular basis so why is the Vicar so

special? The answer: the music, which was universally acclaimed.

The work's demise stemmed

from a series of miscues as is apparent from the writings of

three participants: composer Lehmann, David Bispham (pictured

as the Vicar), who sang the Vicar, and Edith Clegg, his younger

daughter, Sophia.

Why did Liza choose this story? Goldsmith penned

it in 1764 for his own amusement after toiling during the day

as proof-reader of others' writings. His doodlings were taken

up by Dr. Johnson and converted into 60 pounds, a princely

sum that freed Goldsmith from penury. The VICAR proved an instant

hit, the author's whimsical treatment placing him instantly

amongst his nation's leading humourists. Basing her opera on

such a popular tale seemed a wise move indeed.

In her book, she recalled those heady days, "When

I first conceived the idea of a musical version of The Vicar

Of Wakefield, Mr. Arthur Boosey, to whom I intended to

offer the music for publication, at once commissioned Mr. Housman

to write the book and lyrics." Bispham, who also acted as producer,

added, "It was intrusted to Laurence Housman, to whom and to

his sister had been traced the authorship of the beautiful

anonymous work, 'An Englishwoman's Love Letters', which added

a luster to a name already made famous by their brother, Alfred

Edward Housman, author of "The Shropshire Lad."' Laurence it

seems was a gifted wordsmith.

The music was duly composed and the dialogue

created and deemed excellent, but too lengthy. "At the first

rehearsals," Liza noted, "it had become apparent that there

were far too many long dialogues without music. My original

intention had been "opéra comique" as given in Paris

- that is, almost continuous music with very little spoken

dialogue. Our author had apparently not understood this, and,

as his long drawn conversations naturally destroyed the musical

continuity, he was asked to reduce them. Mr. Housman was away

in the country, and wrote back that he could not personally

undertake any excisions or revisions, but gave us carte blanche

to do anything that was found necessary, and said he would

attend the dress rehearsal as a spectator."

There was a casting problem as Bispham described: "I

had trouble in finding a tenor for the part of Squire Thornhill

and was about to engage Walter Hyde when Madame Lehmann begged

me first to hear a young man whose voice had been brought to

her attention. Accordingly, one Sunday afternoon in September

1906, I went with my conductor, the late Hamish MacCunn, and

my manager, Bram Stoker, so long Sir Henry Irving's right-hand

man, to Madame Lehmann's house at Wimbledon... After he had

sung, my dear Liza took me into the next room and enthusiastically

said, `David, if you don't engage him you're a fool. He has

an angel's voice.' `True,' said I, `but he has an Irishman's

brogue.' `He can get over that,' said she fervently."

Liza soon had ruefully to agree, "He proved,

however, to be so inexperienced as regards the stage, and his

Irish brogue was at that time so unquenchable and out of the

character of the young squire, that after a few rehearsals

it was mutually agreed the part did not suit him."

Edith Clegg worded the scene best: "His first

sentence in the play was his undoing. Phwoi! Phwat's the matter-r-r?'

was felt to be out of keeping in the ultra-English Squire Thornleigh,

and despite his lovely voice, after a few rehearsals it was

found necessary to engage another artist."

Squire Thornhill (or "Thornleigh" to Edith),

had to be English so re-enter Walter Hyde, a young tenor from

Birmingham who had scored mightily in the musical My Lady

Molly. Edith again: "I had the pleasure of working for

this first time with my old friend Walter Hyde who took up

the part and had a great personal success with it."

Bispham saw the others as ideal, "Mr. Richard

Temple was admirable as Mr. Burchell and Mr. Lander played

the part of the rascally Jenkinson, which fitted like a glove,

Mrs. Primrose, the vicar's wife, was played to perfection by

that most sympathetic of comediennes, Mrs Theodore Wright;

the daughter Sophia and the boys Moses, Dick and Bill were

performed as if Goldsmith's characters had come to life; while

in the charming Miss Isabel Jay I had the one woman on the

London stage who filled the eye as well as the ear in her rendering

of the part of the wayward but captivating Olivia."

However the Vicar was the star. "How charming

he was," Edith said, "especially when he gave up wearing the

false nose. The strain of keeping that nose in position was

dreadful, and many a time during a performance did he inquire

in his best canonical whisper, `Sophy, is my nose straight?'"

At the dress rehearsal, as promised, Housman

turned up but soon became severely agitated. Liza wrote "with

considerable flow of eloquence (he) told Mr. Bispham that he

could not recognize his play, and that it was utterly ruined." He

threatened to sue, and to force an injunction to restrain performance. "This

was a horrible position for all of us at the eleventh hour,

and under the circumstances we could not see that Mr. Housman

had any earthly right to take such action. In an atmosphere

of threats and counter-threats, the work enjoyed considerable

success during its preliminary tour of two or three weeks in

provincial theatres."

Edith's memories were vivid: "We opened in

December at the Prince's Theatre, Manchester. How well I remember

that day! (It was 12 November) It began with a thick fog -

a regular pea-souper, and I was staying in rooms - my first

experience of `theatrical digs.' My sister rang for matches

to light the gas and after repeated peals, punctuated by long

waits, a very dirty little maid with a bad attack of adenoids

came panting into the room to say - `The Bissis says you boosn't

rig the bell so booch. I'mb cleadig the step and I can't coob!'

Poor child! I am afraid I was a little hard on her. It is difficult

enough to keep clean in Manchester at any time, and the atmosphere

that day was appalling." Soprano Violet Londa sang Olivia at

this stage.

Presumably with every wrinkle ironed out, the

production arrived in London and opened on the 12th to

a packed and expectant house. Housman, ensconced in his complimentary

box seat, "laughed derisively" during a moment of sentiment

in the first act, causing the theatre manager to rise up and

hurry to quell the disturbance. At first he failed to recognize

him, but after a loud exchange, Housman was ejected. The next

day The Daily Chronicle screamed: DISOWNED OPERA - Author

Ejected From The Theatre - `First Night' scenes. The controversy

thus created continued to boil while at the theatre, audiences

went on applauding wildly. Alas, the negative publicity proved

devastating and after a few weeks, the Vicar closed.

Summing up, Liza lamented: "Apart from the

length of the dialogue, which, even after the offending liberties

had been taken with the text, still needed an active pruning

knife, we had chosen the wrong time of year for this type of

entertainment. It was just before Christmas; the winter was

a particularly severe one, and the snow was piled up in the

streets, making them almost impassible. And then the Pantomines

burst forth, and the receipts at the box office, which had

started splendidly, began to languish. By the time the poor

Vicar was to make his parting bow, `business' had already begun

to recover, and the whole company offered to continue playing

at half-salaries, as they believed in ultimate victory." But

theatre management had other plans, deeming a comedy by Paul

Rubens a far safer card, and no other suitable theatre was

available.

And yet press reaction was universally favourable,

The Daily Telegraph view being typical, "Oliver Goldsmith's

simple but fascinating story has been turned to musical account

by Madame Liza Lehmann, and the result of her efforts is altogether

delicious. Number follows number, each more pleasing than the

other, while the orchestration (which she attributed to her

husband Herbert Bedford) is of a particularly delicate yet

rich description."

To Edith Clegg it had a weakness: "The music

was charming, but the book lacked humour, and being `light'

not `grand' opera, a funny man was essential to its financial

success. The humour we did get was sometimes unintentional.

I had a delightful little song to a blackbird. A real bird

was tried at first, but the poor thing was terrified by the

lights and a stuffed one was substituted. One night, just before

I had to bring the cage down to the footlights, one of the

men in the orchestra called up, `Sophy! Your blackbird's hanging

on his perch!' I just had time to put him right side up before

my cue for the song." Possibly she was right but Liza likely

rejected any outright comic touches, thinking both situation

and music were comic enough.

Clearly the main problem was the inadequacy

of the dialogue; it lacked the flow of good opera. One wonders

why Housman was chosen as his writing credentials seemed unsuited

to opera, or as Liza felt, he failed to understand his purpose.

And why did he choose to absent himself during the work's crucial

formative stage?

Housman possessed a somewhat different view,

for according to Kurt Gänzl in the Encyclopedia of the

Musical Theatre, he "flounced angrily out when his overlong

book was cut to make room for the vast amount of music his

composer had supplied." Whatever was true vis-à-vis

libretto vs music, Liza must share some blame in that her lack

of operatic expertise meant that she was unable to spot potential

trouble soon enough nor able to resolve it in time.

The cast seems to have done well. Although

Walter Hyde presented a squire to the manor born, one wonders

if the other Irish tenor's splendid voice would have tipped

the scales favourably, presuming his brogue was sufficiently

tamed. Probably not. Most will have guessed he was none other

than John McCormack.

Was Liza really an operatic composer? No one

now can really say but Steuart Bedford, her grandson, affirms "I

do have a score of the piece and it contains many charming

numbers. Dick's song, `It was a lover and his lass' is particularly

characteristic." So, to conclude on a positive note, in fact,

it is possible for the Vicar to be reawakened. © Charles

A Hooey

Sources: The Life Of Liza Lehmann by

herself, published by T. Fisher Unwin, London, in 1919; A

Quaker Singer's Recollections by David Bispham, published

by the MacMillan Company, New York, in 1920; "As It Was

In My Beginning," an article by Edith Clegg in Opera Vol.

1, No 11, November, 1923. Also thanks to Jim McPherson for

providing Mr Gänzl's report.

Operas

and musicals try and fail on a regular basis so why is the Vicar so

special? The answer: the music, which was universally acclaimed.

The work's demise stemmed

from a series of miscues as is apparent from the writings of

three participants: composer Lehmann, David Bispham (pictured

as the Vicar), who sang the Vicar, and Edith Clegg, his younger

daughter, Sophia.

Operas

and musicals try and fail on a regular basis so why is the Vicar so

special? The answer: the music, which was universally acclaimed.

The work's demise stemmed

from a series of miscues as is apparent from the writings of

three participants: composer Lehmann, David Bispham (pictured

as the Vicar), who sang the Vicar, and Edith Clegg, his younger

daughter, Sophia.