|

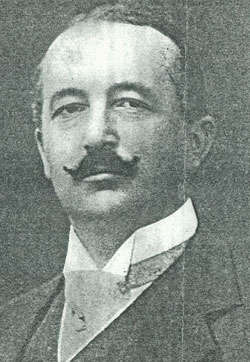

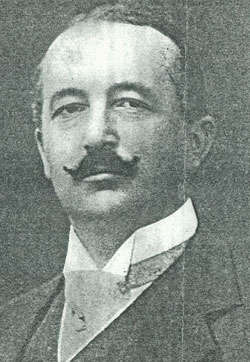

Robert Radford

by

Charles A. Hooey

In the annals of British grand opera, one name stands out

amongst that country’s

stellar bassos. The inimitable Robert Radford was an evil but charming black-clad “Meph” in

Faust, a starry role of many that included a droll and sardonic Osmin

in Entführung, a dignified Sarastro in Die Zauberflöte,

a guilt-ridden Boris Godunov, Fasolt and Hunding in Wagner’s Ring,

a tragic Tsar in Rimsky’s Ivan the Terrible, kindly Father in Louise and

so on. In a 1909 salute, The Musical Standard labelled him most aptly, “Robert

Radford, Deep Bass.” Here is his story, enriched by his own words and those

of his daughter Winifred.

He was born in Nottingham on 13 May 1874, the first of an eventual seven children

for proud parents Elizabeth and Harry Skevington Radford. They called him “Robert

Attenborough” the second name in tribute to his mother’s family.

Papa’s money management for a lace manufacturer meant his first born could

attend private schools. But like most youngsters, Bob found organized music a

thudding bore. “My first recollection is of a small boy, aged nine, who

used to put the clock forward during his piano practice.” The piano may

not have been his choice then but his blood would soon boil with music. “After

all,” he wrote, “my mother was musical and my father had a good voice.”

As one story goes, as a toddler and being bounced on his nanny’s shoulder,

he took a nasty tumble and injured a foot. When it failed to heal properly, he

was left with a permanent limp that actually became an asset, giving his gait

a characteristic swing which was most effective on the stage. Another version

has him felled by polio. Whatever the reason, he could not, as a youngster, emulate

his father, the popular Secretary of the Football Club.

“

As a boy I was one of that ‘band of angels’ who sang in the choir,

the darling of the old ladies and despair of the choirmaster, but I had no cathedral

choir school training as so many other singers had. It was really a toss up with

me as to whether I should go in for singing or art.”

More exciting days came later when in conjunction with several other small

boys aged about 12 to 15, we formed a nigger minstrel troupe. My voice was

a high

treble. I moved from corner man playing the ‘bones’ to being interlocutor

and conductor. The orchestra consisted of a piano (which I played), two violins,

cornet and kettledrum! My clearest recollection is of ‘cracking’ while

singing at a public performance, which ended my career at the age of fourteen.

The song, I remember, was ‘White wings’, a popular ballad which began

on a high note. My voice was breaking at the time, though I did not know it.

Twice the little orchestra played the symphony, twice did I try to begin; and

only gurgles ensued. I then began to giggle hysterically, did not manage to sing,

and eventually went home in tears.”

At least growing up had its plusses. One summer in 1889, fifteen 15 year-old

Bob and pals met to romp by the sea at Skegness as did a lass of seventeen.

A sudden squall sent everyone scurrying under the pier. There Bob met Ada Roper.

At Papa’s urging, he joined the staff of the Burrough Accountant’s

Office as a prelude to becoming a chartered accountant. He spent a miserable

year, relieved only by his “muddling about with music” - that meant

trying to master the piano. How different from eight years earlier! As for accounting, “It

was the one thing in which I took not the slightest interest; to this day I generally

add using my fingers.” However, an amateur accompanist of some accomplishment

did emerge.

The skill proved useful. “Times were hard and being ready to do anything,

I helped form a masked quartet, consisting of four singers and a pianist. In

suits of white duck, with yellow hat-bands etc., we invaded the Henley Regatta, ‘collecting’ by

means of bags at the end of long bamboo poles. Our takings were £36, which

had to be divided among the five of us; and I seem to recollect the two ladies’ costumes

came to about 7 guineas each. We cannot have been very good for the Marguerite

Quartet ceased to be!”

As a student, he suffered an appendicitis attack from which he recovered but

without an operation. In 1901, a flare-up with the serious complication of

peritonitis did result in surgery, but the problem recurred at intervals necessitating

nine

major internal operations in eleven years. All this placed an inordinate strain

on both heart and blood pressure and prevented travel. Regretfully, he had

to decline Thomas Quinlan’s adventures and many invitations to sing abroad.

By 1918, the accumulation of health woes caused a decline in the quality of his

voice. As a student, he suffered an appendicitis attack from which he recovered but

without an operation. In 1901, a flare-up with the serious complication of

peritonitis did result in surgery, but the problem recurred at intervals necessitating

nine

major internal operations in eleven years. All this placed an inordinate strain

on both heart and blood pressure and prevented travel. Regretfully, he had

to decline Thomas Quinlan’s adventures and many invitations to sing abroad.

By 1918, the accumulation of health woes caused a decline in the quality of his

voice.

For now he continued: “Miss Agnes Larkcom in those days used to come to

Nottingham to teach and she encouraged me. Go to London she advised.” When

his father, by now with six other children could not afford the expense, local

benefactors came to the rescue. Before he left, he and Ada became engaged but

marriage would have to wait. “Madame Larkcom gave me an introduction to

Mr. Randegger, whose encouragement meant my farewell to books and figures. I

entered the Royal Academy of Music (in 1896) at the age of 21. Mr Frederic King

was my singing professor.” He carried on parallel lines of study in piano

(E. Morton), harmony (W. Battison Haynes) and elocution (Henry Lesingham). “From

the first my voice had been a real bass, but I remember at the RAM Opera class

singing Carmen’s Toreador - transposed down.” In his first

year, he earned the coveted Westmorland scholarship.

“

With what gratitude one remembers kind help in early days! My two good fairies

were Alberto Randegger and the well-known impresario Percy Harrison. May the

soil rest easy on their bones! The former allowed me to sing Brander in Berlioz’s Faust at

the Norwich Festival (of 1899) with Albani, Edward Lloyd and Andrew Black.

Percy Harrison took me up somewhat and included me on his concert tours.” His

shows were a cut or two above the prevailing ballad concerts. Radford invariably

sang Purcell and Handel with the occasional concession to the prevailing musical

taste, a ballad such as the old German song ‘In cellar cool.’

Early in 1900, he made music at home with the Nottingham Sacred Harmonic Society

and Henry Wood in Sullivan’s The Martyr of Antioch and Acts 1 & 2

in the Paris version of Tannhäuser, a ‘first’ in England.

On 6 October, the patient couple at last tied the knot. He was 26. Almost a year

later, their only child, “Winifred Eva”, was born. Early in 1900, he made music at home with the Nottingham Sacred Harmonic Society

and Henry Wood in Sullivan’s The Martyr of Antioch and Acts 1 & 2

in the Paris version of Tannhäuser, a ‘first’ in England.

On 6 October, the patient couple at last tied the knot. He was 26. Almost a year

later, their only child, “Winifred Eva”, was born.

In 1902, he sang at a Proms concert, his first with forty-nine to follow. In

November, he turned to oratorio in Hull in Parry’s Judith. The

next year, he cautiously entered the primitive world of recording with the

Gramophone

Company, but when reaction was slow, he cut a few discs for Columbia. Still

the public paid little attention, so he agreed when Percy Pitt suggested: “Try

opera.” “My first performance (on 4 May 1904) was as the Commendatore

in Mozart’s Don Giovanni at Covent Garden. On that memorable,

as far as I personally am concerned, night the Don was played by Renaud, and

Journet

and Emmy Destinn were also in the cast. Richter was conducting; a dreadful

ordeal!” Towards

the end of 1905, he sang in scenes from Gounod’s Faust with Dr.

Weekes’s Choral and Orchestral forces during a Three Towns Festival. He

met a comely Marguerite in Caroline Hatchard from Portsmouth and a lifelong friendship

began.

Although opera was fun, oratorio, he knew, put bread on the table. “Though

pursued continually by bad health, my good fairy was looking my way when I was

engaged to sing Judas Maccabaeus for the Handel Festival in 1906. This

was an opportunity, to which I responded by cracking on the top note in ‘Arm,

arm, ye brave!’ and it was a real crack and nearly cracked the Crystal

Palace! This, though a great tragedy to me at the time was not quite fatal, for

I have sung at every Handel Festival since.”

And yet, it was a bumpy road. Singing in Messiah for a small Yorkshire

choral society, “I thought I had knocked the earth flat. I went back to

my hotel feeling very pleased with myself, and settled down to a quiet rest.

But somebody opened the door and said, ‘A heard yo’ sing in T’ Messiah

toneet but - a wouldn’t advise yo’ to do it again!”

An Elijah though drew favour. He was summoned with Agnes Nicholls, Clara

Butt and John Coates to sing before the King and Queen in Memorial Hall at

Eton to help raise funds to restore St. George’s Chapel. “..the place

was so small,” Radford reported, “the singers were only a few feet

from the Royal Family, and we found it very embarrassing, but they stood it very

well, and everything went off all right.” An Elijah though drew favour. He was summoned with Agnes Nicholls, Clara

Butt and John Coates to sing before the King and Queen in Memorial Hall at

Eton to help raise funds to restore St. George’s Chapel. “..the place

was so small,” Radford reported, “the singers were only a few feet

from the Royal Family, and we found it very embarrassing, but they stood it very

well, and everything went off all right.”

To this point he was little known in London, but in the provinces everyone

saw him as the leading and representative English oratorio bass. This situation

was

about to change. Hans Richter and Percy Pitt at the Royal Opera were mounting

Wagner’s Ring in English and both well remembered this bass. In Rhinegold on

27 January 1908, he painted “a sturdy and truculent picture of the giant

Fasolt” and in Die Walküre on the 28th, his “Hunding

promises remarkably well. It was a firmly-drawn piece of work and the music suited

him admirably.” Then, at a concert on 12 February on behalf of the Metropolitan

Police Orphanage, he sang with Wagnerian mates Perceval Allen, Borghild Bryhn

and Edna Thornton, bolstered by Ben Davies and Mischa Elman.

When he portrayed the clean-shaven monarch in Aida on 23 May, off came

his resplendent moustache, never to reappear. And, when Gluck’s Armide was

given in German, he was duly impressive as Aronte, Armida’s priestly advisor,

amidst a cast of stellar vocal quality. Finally, he was an imposing Raimondo

in service to Tetrazzini’s Lucia di Lammermoor.

Early in 1909 after a Ring repeat, the Company gave The Angelus,

worthy music that earned composer Edward Naylor a prize of £500. His luck

evaporated, however, at the première, when a heavy fog rolled in to keep

half the audience at home. Those brave enough to venture forth were fairly satisfied,

especially with Radford’s Abbot Tunstall. Also, he contributed a “sonorous

and imposing Pogner” when the first performance in English of Wagner’s Die

Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Was given on 9 February.

Critic Sydney Grew encountered him at the Birmingham Triennial Festival:

I believe the first time I heard this most satisfyingly virile

singer was in the autumn of 1909. Radford took part in Faust of

Berlioz, in Handel’s Judas

Maccabaeus and in other works...I recall the jovial sardonic humour

he poured into his singing (as Brander); but I recall still more vividly

his

flexible rhythm;

the music is noted in one-crotchet bars, and so it is not easy to ‘scan’ in

respect of rhythmical motive or to blend these motives into phrase; as

Radford sang it, however, it fell into the perfect architecture that Berlioz

had

planned.

From the beginning, one of the admirable features of Radford’s

great voice has been its flexibility. In such passages as the Judas Maccabaeus aria, ‘The

Lord worketh wonders’, his runs were sure as an organ diapason. Then,

by the added virtue of his dramatic vision, he is enabled to make true

character of Polyphemus in Acis and Galatea; showing us a giant lover... but

for his top F and F sharp, he could not sing in Acis, and we should

then have been without the peculiar delight of his, ‘O ruddier than

the cherry.’

Despite the fact both opera-in-English seasons had drawn

excellent audiences and critical praise, the Royal Opera Syndicate declined

to go further with

the idea. And yet, other cities clamoured to hear Wagner’s music in

English. Nicholls, Hyde and Radford obliged with excerpts under Richter,

later with Beecham.

Outside London, the complete Ring received its first exposure in

Edinburgh in 1910, thanks to impresario Ernst Denhof and the Carl Rosa

Company. Most

of the London cast, including Robert, were involved.

Back in London, Thomas Beecham initiated his Opéra Comique experiment

at His Majesty’s Theatre on 12 May though in Les Contes d’Hoffmann Radford

sang only the tiny role of Schlemil. More substantial fare followed in

Stanford’s Shamus

o’Brien, but “a very dignified Father O’Flynn seemed hardly

capable of inventing the trick by which Shamus makes his final escape.”

For the maestro’s mini-Mozart festival on 20 June, he sang in Entführung

aus dem Serail or The Elopement From The Harem, as it was given,

with a Constanze from Paris and a German Belmonte. It pleased a critic: “The

all-important part of Osmin was undertaken with very remarkable skill by Mr.

Robert Radford, who sang the big scena with fine musicianship and

acted his part in admirably finished style.” He followed on 9 July as the burgomaster

Ortolf in Beecham’s English première of Strauss’s Feuersnot.

A heady comedy, it failed to win total favour, despite the dazzling presence

of Carrie Hatchard in the role of Walpurg.

For Beecham his next challenge came at Covent Garden. He had aimed to begin

on 1 October with d’Albert’s Tiefland, but a messy contretemps

between two of his lead singers spoiled this plan. Instead he opened on

the 3rd with Ambroise Thomas’s Hamlet, Tiefland appearing

two nights later with an understudy as Marta. Hamlet was given only

once, Tiefland five

times. Radford sang in both, before adding the Commendatore in Don Giovanni,

Bartolo in Le Nozze di Figaro and four appearances as King Mark

in Tristan

und Isolde each time with different partners. For a ‘first’ on

8 December, he was First Cappadocian in a Salome Beecham had sanitized

to sneak it by the official censors.

In March 1911, the adventurous Denhof was on the move again, taking the

English Ring to

Leeds, Manchester and Glasgow, Radford supplying his heavies. Denhof travelled

in 1912 but this time, although scheduled to sing Pogner and King Mark,

Bob seems not to have appeared. Perhaps he was ill again. He was singing

Wagner

late in

October in a concert Ring in Bristol, when perhaps he appeared in Caractacus.

A bit later he returned to sing Daland in Der fliegende Holländer.

As the autumn of 1912 neared, Radford signed with Denhof for his most ambitious

undertaking to date, a tour embracing several cities. Things got underway

nicely in Birmingham, where he sang in Tristan und Isolde. But,

after a week in Manchester, Denhof realized he had lost £4,000 and decided he had to

throw in the towel. His ally Beecham thought differently. He raced to the scene

to re-structure and two weeks later the tour resumed in Sheffield. Radford’s

adventures thereafter are laid out in the Chronology. Notably he added Hagen

in The Ring. Out of this enterprise emerged Beecham’s Opera

Company, the B.O.C.

After such operatic frenzy, Radford reverted to the sedate world of oratorio.

His rich and noble voice was an asset to the works of Bach as it was to

opera, with his most memorable non-operatic singing coming at a very special

place.

He wrote:

Of all the music making that takes place in England, the most delightful

and satisfying is the Festival of the Three Choirs. Recollections going

back some

years now, of lovely September days in those ancient and beautiful cathedrals

of Gloucester, Worcester and Hereford, with the sun streaming through the

stained glass windows, and of the peace, and loftiness, and simple grandeur

of it all

have seemed to me to be the finest part of Old England and its music making.

There would not be so many pessimists about if they could hear a performance

under these ideal conditions of, say The Dream of Gerontius with

Sir Edward himself at the helm.

Winifred added, “Elgar was still alive during the greater part of my father’s

career, and some of his works were being heard for the first time. He sang in

these works, often with Elgar conducting. The first time I myself met Elgar was

on the steps of Gloucester Cathedral. My father and he were having a deep discussion

about the merits of Woolworth’s pencils.” Too bad they weren’t

arranging to preserve a few of Elgar’s songs. Actually in 1911 with three

other singers he recorded `As torrents in summer’ from King Olaf and

in 1927 two songs`The pipes of Pan’ and `After’. Only the latter

was issued.

In 1914, thanks to Percy Harrison, he took part in a series of ballad-style

concerts. When he visited the Birmingham Town Hall on 2 February, with

Louise Dale, Ada

Crossley and Ben Davies, he found an enormous audience waiting expectantly.

After Wagner’s Parsifal reached public domain on 1 January

1914, the scramble was on to mount it. First to do so, the London Choral

Society

gave a concert performance in English at Queen’s Hall, London on 1 April, 1914,

with Radford as Gurnemanz, John Coates as Parsifal, Carrie Tubb as Kundry and

Dawson Freer as Titurel and Klingsor. Arthur Fagge conducted.

On 4 July, he became part of a most unusual première during Beecham Senior’s

season at Drury Lane. The opera was Josef Holbrooke’s Dylan,

the middle opera in his Cauldron of Annwn, a massive trilogy he

had based on Welsh legends. Conductor Beecham Jr. opined, “I believe much of the

music was liked by those who heard it, but without question both the story and

the text were wholly beyond the comprehension of the Drury Lane audience.” Radford’s

thoughts are not known.

With the country descending into the horrors of war, Bob at forty and unfit,

was unable to serve actively but he could help to build morale. At the

Proms, his glorious singing elevated patriotic songs, ‘There’s only one

England’ and ‘Old England’s a Lion’ while his soothing

ballads were so beloved by the public. No performer was more welcome, for who

would not thrill to ‘The Diver’, ‘In Cellar Cool’ and ‘Rocked

in the Cradle of the Deep’ sung so marvellously. Of course, he often partnered

the amazing Clara Butt at her patriotic soirees.

Never absent for long from serious music, on 29 October 1914 he participated

in the Huddersfield Choral Society’s first Verdi Requiem,

Dr. Coward at the podium. In The Creation in Manchester with the

Hallé on

4 November, he revealed “both the ponderous expression that suggests the

sublime and also the ease and polish that are essential to an adequate execution

of the music. His voice is equally capable of laying down a great beam of broad

tone and of moving gracefully in the upper reaches of the voice. The duets sung

by Miss Hatchard and himself in the closing were the crown of the whole performance.” Then,

back home in Nottingham on 12 November, he received a hero’s welcome when

he sang with others in a Railway Orphanage concert.

Quite a different experience awaited in Liverpool. On 15 December, the

Philharmonic Concert offered the first performance in England of Gabriel

Pierné’s

mystical legend, The Children’s Crusade. In this 13th century

tale, Bob was ‘An old sailor’ and ‘A Voice from on high’. The

music sung by 75 crazed youngsters proved a harrowing experience.

In 1915 as Easter neared, he recorded Memories of Elijah (an arrangement

of music from the oratorio) with Edna Thornton and Walter Hyde. Then, he

joined Myra Hess and Beecham on 19 June for a Proms Concert in the Royal

Albert Hall

to sing Vulcan’s Song from Gounod’s Philémon et Baucis and

Ethel Barn’s ‘Soul of Mine’. At this juncture, Beecham was

flying high with Opening Day looming for his opera-in-English season at the Shaftesbury

Theatre. Although he had other irons in the fire, Bob was intrigued. In October,

he appeared in Faust and, as if to punctuate the devil’s menace,

so the story goes, a zeppelin hovered overhead dropping bombs. Fortunately, the

theatre escaped damage.

Hubert Bath’s deft hand had arranged music for the Memories of Elijah recording,

so perhaps Bob was reciprocating when, on 26 January, 1916, he appeared

with the enterprising Wakefield and District Choral in Bath’s Wake of o’Connor.

It was “sung with spirit” by himself with Miss Felissa, Eva Roberts

and Herbert Teale. He also had a part on 4 March with Edward German in Dan Godfrey’s

annual Bournemouth concert.

That Spring Tommy Beecham set up in the more spacious Aldwych Theatre and

opened on 15 April with Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte. His

Sarastro was, who else? Radford was ideal; in fact, he seemed predestined. “Once Beecham

was conducting a rehearsal, and at one place in Sarastro’s recitative,

where one usually goes up to C, Beecham pointed down, and I dived beneath the

stave. It ‘came off’ and ever since I have sung the low C.” “His

voice,” according to his daughter, “ranged from about F sharp above

the bass stave to the C below it. In private, at home around the piano he had

no trouble descending to A natural below the bass stave.”

Now, Beecham posed a question, “You know, I’m giving Boris Godunov in

Manchester and I’d like you to be the first English Boris.” This

was great news and Bob began working furiously under the maestro’s tutelage.

Alas, it was not to be, as Winifred explained, “Unkind fate intervened

for my father, shortly before the opening performance, was taken very ill and

Beecham was obliged to send for a bass from Paris named Auguste Bouilliez.” Owing

to his presence, the opera was sung in French. Bob did return as King Mark and

as Varlaam.

Back at Aldwych, he first offered his usual Wagner and Gounod, but on 24

July 1916, he unveiled his classic Osmin in Entführung aus dem Serail.

After so many serious roles, such drollery truly delighted. It was an odd

occasion: festive on one hand as a new production, but sad too, for it

served as a benefit

for six orphaned children of Enrique Granados and wife lost when the Sussex

was torpedoed. Everyone stood as the Spanish National Anthem was played

followed by the company coming on stage to sing one verse of the British

Anthem. He

also

sang in Faust on the 29th with Miriam Licette and Gerald O’Brien.

This role he had modelled on that of Pol Plançon, so according to French

custom, he dressed in black.

On 15 October, a new lion in the person of Norman Allin, burst upon the

scene, though the Old Hebrew in Samson et Dalila hardly suggests ‘bursting’.

Ten years Radford’s junior, he was at first overshadowed by his illustrious

colleague, but in time he would prowl the same lofty plateau and offer his own

King Mark, Ramfis and Bartolo.

But the veteran had a roar or two left. On 16 November, he sang in a concert Faust in

Nottingham, not as the black devil now but “a staid gentleman in evening

dress.” Fellow townsmen were quick to accord him “an enthusiastic

reception, as (he) sang with superb effect, both in solos and in concerted numbers.” Fetching

too were Caroline Hatchard and Frank Webster for conductor Gill.

During Beecham’s lengthy season then underway at Aldwych, Bob found himself

facing another new role. The maestro had created a public for grand opera in

English, so he tantalized further by giving Charpentier’s Louise late

in January. The central figure was brilliantly played by Miss Licette with

Radford “an

excellent Father, genial and picturesque; d’Oisly was Julian; Miss Clegg

the Mother, though with rather too much of the British matron about her. The

place was packed from floor to ceiling.”

Radford finally came to grips with his Boris Godunov creation on

3 March 1917 with BOC in Birmingham. Thus, he was the first English Boris after

all! He sang the part again in Edinburgh on 9 March, adding Osmin on the

12th. Three days later, he was in Manchester with Beecham and the Hallé to sing

the King in Act I of Lohengrin with Agnes Nicholls and Walter Hyde

and Gurnemanz in the Grail Scene from Parsifal, a concert they repeated

in Bradford the next day. Back in Manchester on 22 March he sang in scenes

from Boris and Faust at

a Pension Fund Concert, and stayed for more opera with BOC.

That summer Beecham was on the move again, upwards and grander, to the

cavernous Royal Theatre at Drury Lane, but another bout of illness kept

Bob from enjoying

all the excitement. He also lost three plums: chances to sing Boris in

English in London, (an honour that went to American Robert Parker), to

repeat Louise and

to sing Dr. Bartolo in Le Nozze di Figaro in what proved to be a

sensation!

Fit again, he rejoined Beecham on 24 September to present a Bartolo that

was “a

most entrancing representation, despite the only too-audible bombardment by air-defences.” Three

nights later, as the first Englishman to sing Boris in English in

London, he was “magnificent both as to voice and intensity of dramatic expression.” Oddly,

when Allin sang Boris, Newman rated him “the finest we’ve had in

England”, conveniently overlooking Radford’s remarkable study.

His musical scene continued to revolve mainly between London, Manchester

and Birmingham. In the latter city on 7 October, he gave a concert under

Cowen’s

direction that evoked enormous enthusiasm. He came back on 28 November to sing

arias from Boris Godunov and Entführung aus dem Serail under

Beecham’s guidance and ‘Shepherd, see thy horse’s foaming mane’ accompanied

at the piano by Appleby Matthews. He also left on wax The Mikado,

the first of five Gilbert and Sullivan creations he helped to preserve.

For the

first five or so months of 1918, he was an active bass with Mozart and

Gounod’s Faust,

but the high point came on 14 June when Die Walküre was given “before

an audience not even Drury Lane has often seen.” Beecham conducted the

opera for the first time, inspiring his singers as usual. Radford was magnificent

as Hunding.

Despite his financial woes, Beecham kept his charges on the go. In Manchester,

Bob shepherded Miriam Licette and Webster Millar through Roméo et Juliette.

Then on 24 March, back in London, this threesome tackled Louise.

For Easter, he sandwiched King Mark between two performances of Bach’s great Mass

in B Minor. In April, he sang the title role in Rimsky Korsakov’s Ivan

The Terrible with Jeanne Brola and Walter Hyde. Nor did he forget his

fans, popping up at a Chappell ballad concert with Louise Dale, Madame

D’Alvarez,

Gervase Elwes and Hubert Eisdell. He had his oratorio and concerts but the opera

scene looked gloomy because of the end of Beecham’s enterprise. However,

all was not lost.

The British National Opera (B.N.O.C): The Beginnings

Radford continues:

"What a miracle Sir Thomas Beecham performed

for Opera in this country, and what he could do again if

he liked! I have often been asked

exactly when the

first

idea of a National Opera, on the lines of the present company, was

mooted. Doubtless readers will recall that Beecham’s

last Season was 1920, it finishing in tragic circumstances.

That autumn the artists of his

company started

out to fulfil

the provincial engagements already booked to the old company with the

scenery and properties which they rented, at a rather high figure,

from the Covent

Garden Syndicate.

Prominent in this plucky attempt to keep the standard flying were Webster

Millar and Herbert Langley. They carried on until just before Christmas 1920

but owing

to the fact that the scenery and props were no longer at their disposal they

had to give up the tour.

Then in the Spring of the next year a meeting was held of the orchestral

artists, singers and conductors to discuss plans for the formation of a new

company.

It was realised that the public, owing to past records of opera companies,

would

be very dubious of the success of such an undertaking. However we finally

floated a limited company. These first meetings were held at the offices

of the Orchestral

Union, and in many ways the idea of co-operative organisation actually emanated

from that body.

We worked hard all that summer and autumn to raise capital and to get

things ship-shape; but although our company was actually formed in July,

it was

impossible to obtain a sequence of dates until the following February

when, after long

weeks of rehearsal at the Surrey Theatre in London, we started our career

at the Alhambra,

Bradford."

In Aida, he sang Ramfis with Beatrice

Miranda and Tudor Davies, but all eyes were glued upon the Amneris,

Edna

Thornton, Bradford’s

own. After fourteen operas in two weeks, and still reeling from the deadly

flu epidemic,

the troubadours visited Liverpool, Edinburgh, Leeds and Halifax, before

arriving at Covent Garden on 1 May. Here Bob faced a mighty challenge:

twenty-two performances

in seven weeks. It began with Wagner’s Ring, its first

in London since 1914, then “Dear old Meph”, Louise,

Sarastro, King Mark and Pogner, a role he had last sung in 1913.

He would retain

it to the

end of

his career. Asked how often he had sung in public, he was at a

loss somewhat, but ventured an estimate, “three thousand.”

Interestingly late in January 1921, at the Gramophone studios with

Violet Essex, Edna Thornton and others, he recorded the Gilbert and

Sullivan opera Patience,

setting down three scenes. However Rupert D’Oyly Carte objected

to his singing and he was replaced by Frederick Ranalow.

Concerts included a visit to the Royal Albert Hall on St, Cecilia’s Day,

22 November 1922 on behalf of a Coleridge-Taylor charity. A choir of 1000 voices

swelled in support of Carrie Tubb, Esta D’Argo, Ada Crossley, Ben Davies,

Gervase Elwes, Julien Henry and Radford as he intoned ‘Thou art risen,

my beloved’ by the composer.

A B.N.O.C. regular in the spring of 1923, he sang in Rhinegold on

19 March to begin Glasgow’s first complete Ring, his

Fasolt and Allin’s

Fafner setting a very high standard indeed in singing, acting and

make-up. In Aida that

closed the season, Robert’s resplendent Ramfis helped create “one

of the finest ( Aidas) ever heard in England.”

He had first met Verdi’s music in his youth as the Pharaoh

in Aida.

Later he would advance to Ramfis and sing the Requiem as

a Festival specialty. “I

was only looking over my old ragged copy of the Verdi Requiem the

other day, with its marks and pencil markings, and I remembered

that they were copied

from Randegger’s score, which had been marked by Verdi himself.

Thus do the generations link up in our art.”

That summer at Covent Garden, the drawing card was Nellie Melba,

who came to further the cause of opera in English. She sang with

Radford in Faust on

21 June and in a later performance with Edward Johnson and conductor

Frank St. Leger. Radford was also part of a revival of Louise which

rode on Leah Rusel-Myre’s “perfect character study”, and yet a performance

with Miriam Licette drew criticism of the scene between father and daughter, “I

wish he’d keep still sometimes, just for a moment. He’s moving his

arms, his legs, or his body the whole time.” Surely the real culprit was

the composer’s lengthy, languid music.

Robert was Ramfis when Aida closed the season on 30 June.

The company responded though on 5 July to give Tristan und Isolde as

a benefit for Frau Wagner, who was in dire straits due to the mark’s tumble and a lack

of royalties since 1914. In appreciation of the gift of almost £550, Siegfried

Wagner wrote, “Mrs. Wagner is very grateful. England can be sure that she

has enabled Wagner’s widow to spend the rest of her life easily and comfortably.”

Wagner’s music was very much with Bob as 1924 began. With

B.N.O.C. at Covent Garden, he sang Pogner in Meistersinger on 7 January.

It was a special time as Beecham returned to conduct, dispensing

spicy quips as of old. A

performance of Siegfried was going well on the 25th until

Florence Austral took ill; it was terminated after Act II. Not to

cheat the patrons,

Bob rushed on

stage

with Beatrice Miranda and Hyde to give Act I of Die Walküre.

At the time, the Wembley Exhibition was drawing visitors in hordes,

so Felix Weingartner

with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra chose to contribute a performance

of Beethoven’s

Ninth Symphony. Bob added his blessed sonority to the ‘Ode to Joy’.

With the National Opera, Bob checked into His Majesty’s Theatre in London

for a season in June and July. It was a signal event (no pun intended) as a B.B.C.

microphone carried all or parts of operas to suitably equipped listeners. It

began on 5 June when Bob, “in excellent voice”, sang

Bartolo in Figaro.

Eight nights later as the crew presented Tannhäuser,

he sang a rare Landgrave, lighting up the airways during Act I. On

the 19th, he sang

Pogner

in Meistersinger, Act 3 being aired. On 1 July, Entführung was

given, Act 3 being broadcast with Bob the likely Osmin. Finally on

the 9th in Die

Zauberflöte, he was surely Sarastro, but with little to

do in Act I, the portion that was broadcast.

In 1922, when asked what music was his private delight he said, “In four

letters B-A-C-H. When I need a tonic I sit down and play Bach, cantatas and so

on. For pleasure in actual singing give me Handel, Mozart, Verdi and Wagner -

all knew how to write for the bass voice.” So, when Bach’s Coffee

Cantata was staged in London as Coffee and Cupid, he would

have been at home as a curmudgeonly Schlendrian. He left records

of this music,

made by

the electrical process.

When B.N.O.C. rolled into Liverpool in February 1925 an eager fan,

Frances Robinson, was waiting. Her programme shows that Radford

on the 20th sang

King Dodon in

Rimsky-Korsakov’s Coq d’Or. “Aunt Fay obviously loved

the bloke, as she always spoke of him,” nephew John recalled. In London, “Radford

and Allin (as Polkan) did capitally in clownish parts.” In print, Bob wryly

observed: “Making noises with the neck is a curious way of earning one’s

daily bread, and I have been doing it for over twenty years under all sorts of

conditions.” The neck was working on 25 May during a benefit

for Emma Albani with Melba, Ben Davies, Rosina Buckman and Dinh

Gilly as

Landon Ronald accompanied.

In September, he decided to cast his lot with Wilfred Stephenson,

who was assembling people to tour fifteen centres in north central

England.

His modus

operandi

was simple: “Give ’em top artists at bargain prices and they’ll

come.” They packed halls wherever he went. One of Bob’s celebrity

treats came at Queen’s Hall in Hull on 10 April 1926.

In 1927, in stark contrast, he toured as Basilio in Rossini’s Il Barbiere

di Siviglia with Miriam Licette, Heddle Nash and John Barbirolli.

But, he believed passionately in opera in English, so expended

much time and energy

on

B.N.O.C. matters. He was also a strong advocate of government support. “Just

refund all of the £90,000 in Entertainment Tax, or even half of it and

we’ll be solvent!” His arguments fell on deaf ears, and on 5 April

1929, after a Pogner at Golders Green, the curtain descended on Bob Radford’s

stage career. The next day it closed on the B.N.O.C.

Those must have been heady days. Sydney Russell, a fine character

tenor for B.N.O.C., wrote, “I do not believe that it would be possible to find a happier or

more contented little band of artistes.. team play is always the first thought,

and other artists’ successes are sincerely enjoyed..”

Radford had begun vocal coaching at the Royal Academy of Music in

the mid-twenties, passing on his wisdom to mezzo Rispah Goodacre,

baritones Henry Cummings

and Roy Henderson and, later to bass Norman Lumsden. When asked in

the early thirties

to list his favourite singers, Bob included Lumsden, while fondly

recalling mates of the past, Perceval Allen, John Coates, Walter

Hyde and Alfred Heather.

In a letter to Graham Oakes, Lumsden wrote:

When I went for my audition, I was shown into his music room, a

large, sunny room which was, if my memory serves me correctly,

devoid of

any unnecessary

furnishing, (with) a grand piano and walls covered with autographed

photographs of his contemporaries.

When he came into the room, I instantly felt I was in the presence

of ‘a

great.’ He had a great charisma and an exuberant personality, very warm,

and in modern terms would be described as ‘sending out friendly

vibes.’

During the lessons, I got occasional glimpses of what his voice

could have been. Once he was urging me to learn the Korbay settings

of

Hungarian Folk

songs, one

in particular was ‘Had a horse’ - a tragic song with each verse ending

with ‘But no matter, more was lost at Mohac’s Field.’ (Hungarian

soldiers were wiped out by a Turkish army of much greater numbers).

He sang part of it through to me, just using half voice, quite

softly. His

health was failing,

but the expressive range he conveyed was most moving, and it left

an impression that I have not forgotten all these years after.”

And writing to Wayne Turner, Lumsden portrayed Radford as “a personality

exuding friendliness, plus a great ‘presence’- one of the essentials

of a good performer - a projection of personality, something that comes across

before the artist has started - modest people ‘turning it on’ and

becoming larger than life. In Messiah, when you stand up

to sing ‘Thus

sayeth the Lord’ let it rip - and look ’em straight in the eye -

otherwise, it looks as if you’re reading ’em a telegram

from God!”

He was no believer in all work and no play as fading photos attest.

Suitably attired, fishing poles at the ready, he and three pals

prepare for an

angling session. Certain golf greens knew his unsteady step while

he’d

often take pen in hand to dash off the occasional poem or create

a fanciful sketch.

Winifred recalled how those who knew and loved him appreciated “his personality,

his great courage, his wit, infectious sense of humour and love of life. He had

the blessed gift of laughter and often amused himself by writing light verse.” Why,

he was even a song composer! Ever the gregarious sort, he was both

a smoker and an imbiber, but in moderation he claimed. With his

shaky health

such indulgence

seems ill-advised, but who then understood the peril?

In retirement he lived comfortably in a charming home in St. John’s

Wood, surrounded by all those portraits. There, within sight of

his fifty-ninth birthday,

his beleaguered heart gave out on 1 March 1933.

Ada and Winifred lived on until a bomb demolished their cosy abode

during World War II. After moving in with Caroline Hatchard and

family, Ada

would sit by

a chest overflowing with mementos and delight visitors with tale

after tale, not

about Bob’s triumphs, but of his mischievous pranks. A lovable

character, yes, but a true titan amongst singers.

Winifred Radford became a successful singer, a soprano who sang

four seasons at Glyndebourne in the thirties as Barbarina, Zerlina

and

Cherubino. A specialist

in the French song repertoire, she taught at the Guildhall School

of Music in 1955, staying fifteen years. She died on 15 April 1993.

Sources

1) The words of Radford himself originated in:

“ Robert Radford” The Musical Times, May 1, 1922

“

I Remember” by Robert Radford, Opera, April 1924*

“

The Future of Opera in England” by Robert Radford. Opera, January,

1923*

2) Winifred’s words from:

“

Robert Radford” by Winifred Radford, Lecture at the Institute

on 5 March 1970, reproduced in Recorded Sound.

3) The account is enriched through research by the now-defunct

Beecham Society of England

and reported

by Maurice Parker and Tony Benson. Thus, Radford’s work with

Beecham is emphasized but with others it is less well defined.

4) Other writings about Radford consulted:

“ Robert Radford, Deep Bass” The Musical Standard, March 21,

1908

“ Robert Radford” Favourite Musical Performers by Sydney Grew,

T.

N. Foulis, London & Edinburgh, October 1923

“

Robert Radford” article in the Nottingham Journal, 3-8-1928

“

A Mingled Chime” by Sir Thomas Beecham, Hutchinson & Co.

1944

“

Robert Radford” by William G. Kloet, The Record Collector,

1962, (with fascinating interview).

Music In England, 1885 - 1920 by Lewis Foreman, Thames Publishing,

1994

The Proms In Pictures, BBC Books

The Musical Times - various

“

Robert The Devil” by Tully Potter, IRC 2001

“

Robert Radford” - unpublished biography by Wayne Turner

Sir Thomas Beecham - A Calendar of his Concert and Theatrical Performances by

Maurice Parker, 1985 and Supplement by Tony Benson, both supplied

by Denham Ford.

John Coates, a biography by Dennis Foreman, The Record Collector Vol.

38 No. 2, April - June 1993, pp 82-109

Ben Davies, a biography by Dennis Foreman, The Record Collector Vol.

41, No. 3, Sept. 1996, p. 169

“

I Remember” by Sydney Russell, Opera, June 1923, p.

31*

* Opera referred to here was a short-lived publication of

the mid 1920s, not the well-known magazine of today.

Acknowledgements

I also very much appreciate the assistance of Paul Campion in London

for the family background, Ewen Langford, Caroline Hatchard’s

son, for his insights, the late Denham Ford for the Beecham data,

Norman Staveley

in Hull, John Robinson

in Liverpool, Graham Oakes in Wales, Dennis Foreman and Euan Gibby

in Nottingham, Mike Langridge in Rustington and the late Wayne

Turner of

Deeside. A great,

great team of supporters! Many thanks to all.

The Editor thanks Tully Potter and Euan Gibby. Christian Zwarg, Paul

Steinson, John Bolig, Peter Chaplin and Dave Mason provided information

for the discography.

Special thanks to Christian for checking it,

Published in the Record Collector Vol. 54, No. 3, September

2009, and reproduced with permission.

|

|

|

As a student, he suffered an appendicitis attack from which he recovered but

without an operation. In 1901, a flare-up with the serious complication of

peritonitis did result in surgery, but the problem recurred at intervals necessitating

nine

major internal operations in eleven years. All this placed an inordinate strain

on both heart and blood pressure and prevented travel. Regretfully, he had

to decline Thomas Quinlan’s adventures and many invitations to sing abroad.

By 1918, the accumulation of health woes caused a decline in the quality of his

voice.

As a student, he suffered an appendicitis attack from which he recovered but

without an operation. In 1901, a flare-up with the serious complication of

peritonitis did result in surgery, but the problem recurred at intervals necessitating

nine

major internal operations in eleven years. All this placed an inordinate strain

on both heart and blood pressure and prevented travel. Regretfully, he had

to decline Thomas Quinlan’s adventures and many invitations to sing abroad.

By 1918, the accumulation of health woes caused a decline in the quality of his

voice.  Early in 1900, he made music at home with the Nottingham Sacred Harmonic Society

and Henry Wood in Sullivan’s The Martyr of Antioch and Acts 1 & 2

in the Paris version of Tannhäuser, a ‘first’ in England.

On 6 October, the patient couple at last tied the knot. He was 26. Almost a year

later, their only child, “Winifred Eva”, was born.

Early in 1900, he made music at home with the Nottingham Sacred Harmonic Society

and Henry Wood in Sullivan’s The Martyr of Antioch and Acts 1 & 2

in the Paris version of Tannhäuser, a ‘first’ in England.

On 6 October, the patient couple at last tied the knot. He was 26. Almost a year

later, their only child, “Winifred Eva”, was born.  An Elijah though drew favour. He was summoned with Agnes Nicholls, Clara

Butt and John Coates to sing before the King and Queen in Memorial Hall at

Eton to help raise funds to restore St. George’s Chapel. “..the place

was so small,” Radford reported, “the singers were only a few feet

from the Royal Family, and we found it very embarrassing, but they stood it very

well, and everything went off all right.”

An Elijah though drew favour. He was summoned with Agnes Nicholls, Clara

Butt and John Coates to sing before the King and Queen in Memorial Hall at

Eton to help raise funds to restore St. George’s Chapel. “..the place

was so small,” Radford reported, “the singers were only a few feet

from the Royal Family, and we found it very embarrassing, but they stood it very

well, and everything went off all right.”  Wagner’s music was very much with Bob as 1924 began. With

B.N.O.C. at Covent Garden, he sang Pogner in Meistersinger on 7 January.

It was a special time as Beecham returned to conduct, dispensing

spicy quips as of old. A

performance of Siegfried was going well on the 25th until

Florence Austral took ill; it was terminated after Act II. Not to

cheat the patrons,

Bob rushed on

stage

with Beatrice Miranda and Hyde to give Act I of Die Walküre.

At the time, the Wembley Exhibition was drawing visitors in hordes,

so Felix Weingartner

with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra chose to contribute a performance

of Beethoven’s

Ninth Symphony. Bob added his blessed sonority to the ‘Ode to Joy’.

Wagner’s music was very much with Bob as 1924 began. With

B.N.O.C. at Covent Garden, he sang Pogner in Meistersinger on 7 January.

It was a special time as Beecham returned to conduct, dispensing

spicy quips as of old. A

performance of Siegfried was going well on the 25th until

Florence Austral took ill; it was terminated after Act II. Not to

cheat the patrons,

Bob rushed on

stage

with Beatrice Miranda and Hyde to give Act I of Die Walküre.

At the time, the Wembley Exhibition was drawing visitors in hordes,

so Felix Weingartner

with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra chose to contribute a performance

of Beethoven’s

Ninth Symphony. Bob added his blessed sonority to the ‘Ode to Joy’.  In retirement he lived comfortably in a charming home in St. John’s

Wood, surrounded by all those portraits. There, within sight of

his fifty-ninth birthday,

his beleaguered heart gave out on 1 March 1933.

In retirement he lived comfortably in a charming home in St. John’s

Wood, surrounded by all those portraits. There, within sight of

his fifty-ninth birthday,

his beleaguered heart gave out on 1 March 1933.