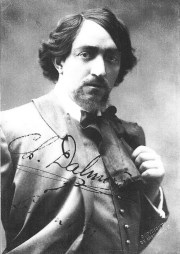

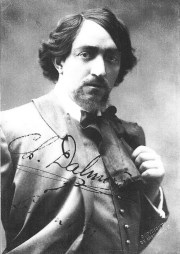

CHARLES DALMORÈS

by Charles A. Hooey

Not surprisingly, this French artist sang primarily in his

native tongue during his first few years on stage and continued

to feature French operas in his repertoire throughout his career.

He did, however, come to believe opera should be sung in its

original language and when he developed a love for Wagner’s

music, he studied German assiduously. As well he learned Italian

and English. His voice was described as a noble organ, manly,

tender and always sympathetic. He sang with great skill, was

always musical and as well was as an accomplished actor. He

achieved fame through outstanding seasons in London, New York,

Chicago, Boston and elsewhere. His name was ‘Charles Dalmorès’.

EARLY TIMES

In describing his beginnings as ‘Charles Léopold

Brin,’ he wrote: “I was born on the thirty-first

of December 1871 in the town of Nancy, France. Soon I was joined

by two brothers, Pierre-Victor, born in 1875 and Henry Alphonse,

born in 1877. My parents were poor, but honest, and for many

years I, too, was poor, but honest. This is not an unusual beginning

in the artistic world and I must say that I never felt the misfortune

of it, as some might imagine.” As early as six years of

age, young Charles showed he had musical talent and instruction

commenced, but his father decided his son should have a career

in business. “Ugh! How I hated it! He wanted me to be

an architect, because he believed that would be a respectable

and profitable career for a man. Music, he did not think was

a serious profession.” When this work and an attempt to

make him a jeweler’s designer failed, Charles was finally

allowed to concentrate on a career in music. He paved the way

for both of his brothers to become musicians too.

“I studied first at the Conservatory at Nancy, intending

to make a specialty of the violin. Then, I had the misfortune

of breaking my arm. It was decided thereafter that I had better

study the French horn. At the age of fourteen I secured a position

in the opera house at Nancy, playing the French horn. My performances

at that time were not remarkable, but the elements of music

were awake in me, and I was happy. I was a cantor in a Jewish

temple, although not of this faith, and it became necessary

for me to rise very early.” At seventeen, “I went,

with a purse made up by some citizens of my home town, to enter

the great Conservatory at Paris. There, I studied very hard

and succeeded in winning my goal in the way of receiving the

first prize for playing the French horn. I also studied fugue,

counter-point, composition and harmony.” “My first

experience in Paris was at the old Théâtre du Clugny,

near the Boul’vard St. Michel. For a time I played under

Colonne, and between the age of seventeen and twenty-three in

Paris I played with the Lamoureux Orchestra at the Opèra,

the Opèra-Comique - practically everywhere.”

“In my twenty-third year in 1894 I became one of the professors

at the Musical Conservatoire at Lyons and while playing in the

orchestra of the Opéra, I gave lessons on the violin

and French horn. These five years were constant work, with very

little money.

I made $2.00 a day. I was rich. It was my custom when illustrating

the phrasing of some musical idea to my pupils, to hum or sing

it over for them. Among the professors was the celebrated basso,

M. Dauphin, who has sung for fourteen years at Covent Garden

and the other great opera houses in the world. He overhead me

singing and I owe him the fact that I am a tenor in grand opera

today. I studied with him for two winters, helping out my expenses

by singing solos at the Casino in Aix-les-Baines. M. Dauphin

ultimately sent me to Paris to study grand opera with tenor

Vergnet. My chance came after a concert in a private house at

Nancy where I sang some of the motifs of ‘Götterdämmerung’,

‘Meistersinger’ and ‘Siegfried.’

Though his efforts to climb out of the pit onto the stage won

only ridicule at first, they gave him instruction and encouragement

to continue.

The Director of the Théâtre des Arts de Rouen happened

to hear him and engaged him for a three year period to sing

with the opera company. He managed to raise enough money to

purchase three costumes to be worn in the operas of ‘Hérodiade’,

‘L’Africaine’ and the ‘Huguenots’,

and in the year of 1899-1900, the director presented him with

$500 to purchase other costumes. His income was not large by

any means but he was earning $300 a month while studying two

operas a month and acquiring a repertoire in French.

He made an appearance as a tenor in 1899 under the name of ‘Charles

Brin’, portraying Loge, in French, during a concert performance

of Das Rheingold. Deemed a success, the good citizens

of Rouen instructed the captain of police to hold up a sign,

‘Approved’, according to a local custom of acclaiming

an artist. His actual début came in Rouen on 17 February

1899 in the title role of Wagner’s Siegfried when

the opera was given for the first time in France. The cast also

featured Mme. Bossy as Brünnhilde, Eva Romain (Erda), M.

Grimaud (The Wanderer) Féraud de Saint-Pol (Alberich)

and Mlle. Lemeignan (Forest Bird). Then, wearing his own costume

on 6 October 1899, he appeared as Nicias in Massenet’s

Hérodiade - he would appear often in this opera.

Next on 23 December, he sang Doc-Liet in Thi-Teu by Frederic

Le Rey, a local composer, with Mme. Bossy as Thi-Teu and Messrs

Grimaud and Féraud de Saint-Pol in other key roles.

At this time at La Monnaie in Brussels, the new managers, Messrs

Kufferath and Guidé were busily signing new talent, and

they managed to lure Brin into their ranks. As he was still

under contract to the Rouen Opera, Monnaie was forced by the

Civil Court to pay 20,000 francs to the Director of the Rouen

Opera for having broken the tenor’s contract.

JOINS LA MONNAIE OPERA IN BRUSSELS, 1900-1906

During his initial season at the Théâtre Royale

de la Monnaie, now known as Charles Dalmorès, he was

incredibly busy, with no fewer than eight different roles, all

new to his repertoire, including two by Wagner. He began on

26 September 1900 in the title role in a Saint-Saëns’s

opera, gaining this reaction: “the revival ofSamson

et Dalila last Wednesday was the début of ‘Charles

Dalmorès’, who will have to support the Wagnerian

repertoire this year. It was a brilliant victory. He brings

many qualities which conquered the public. The voice is of a

beautiful, metallic timbre, thrills in all its registers and

is without the use of bad taste which often characterizes the

forts tenors. The voice is capable of beautiful demi-teintes

(half shades) and is handled with complete security. Twice,

with secure intonation, he sang high Bs at the end of Act 2.

As an actor he is at ease, avoiding the conventional gesture.”

His Dalila, Jane D’Hasty, would be described later as

having ‘a volcanic temperament’ and one who ‘would

set the stage on fire’. It must have been quite an evening

- and quite a début it was!

Back

on stage on 20 November for the first of fifteen performances

of Tristan et Isolde, he shared the role of Tristan with

Ernest van Dijck with Russian soprano Félia Litvinne

(Isolde), Marie Brema (later Georgette Bastien) (Brangäne),

Gustav Schwegler (King Marke) and Max Buttner (Kurvenal) with

Felix Mottl conducting. Next he portrayed Araquil in Massenet’s

La Navarraise with Marguerite (Zina) de Nuovina as Anita.

She was Santuzza when Dalmorès sang in Cavalleria

Rusticana, possibly in Italian, though all else was in French.

Next, he was Raoul de Nangis in Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots,

following on 9 February 1901 as Julien in the first of twenty-three

performances of Charpentier’s Louise with Claire

Friché as Louise, Henri Seguin and Jane D’Hasty

as the parents (see left). After appearing as Admète

in Gluck’s Alceste (see right), he was Siegmund

in Wagner’s La Walkyrie with Félia Litvinne

as Brünnhilde, Jeanne Paquot as Sieglinde.

Back

on stage on 20 November for the first of fifteen performances

of Tristan et Isolde, he shared the role of Tristan with

Ernest van Dijck with Russian soprano Félia Litvinne

(Isolde), Marie Brema (later Georgette Bastien) (Brangäne),

Gustav Schwegler (King Marke) and Max Buttner (Kurvenal) with

Felix Mottl conducting. Next he portrayed Araquil in Massenet’s

La Navarraise with Marguerite (Zina) de Nuovina as Anita.

She was Santuzza when Dalmorès sang in Cavalleria

Rusticana, possibly in Italian, though all else was in French.

Next, he was Raoul de Nangis in Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots,

following on 9 February 1901 as Julien in the first of twenty-three

performances of Charpentier’s Louise with Claire

Friché as Louise, Henri Seguin and Jane D’Hasty

as the parents (see left). After appearing as Admète

in Gluck’s Alceste (see right), he was Siegmund

in Wagner’s La Walkyrie with Félia Litvinne

as Brünnhilde, Jeanne Paquot as Sieglinde.

In some respects, 1901-1902 mirrored the first season with repeats

of Louise, La Navarraise, Samson et Dalila, and La

Walkyrie with new roles being Faust, Lohengrin

and Die Götterdämmerung. All of Wagner’s

music was sung in French. The next season could have been labeled

his ‘Wagner Year’ as he sang in all four operas

of The Ring plus Tristan et Isolde and Lohengrin

with Faust and Louise added.

In some respects, 1901-1902 mirrored the first season with repeats

of Louise, La Navarraise, Samson et Dalila, and La

Walkyrie with new roles being Faust, Lohengrin

and Die Götterdämmerung. All of Wagner’s

music was sung in French. The next season could have been labeled

his ‘Wagner Year’ as he sang in all four operas

of The Ring plus Tristan et Isolde and Lohengrin

with Faust and Louise added.

The following summer he achieved a true milestone when on 17

May 1902 he sang at the Théâtre de Château

d’Eau in Paris as Siegfried in Die Götterdämmerung

or Le Crépescule des Dieux, as it was sung in

French. Other artists included Félia Litvinne (Brünnhilde),

Jeanne Leclerc (Gutrune), Rosa Olitzka (Waltraute), Henri Albers

(Günther) and Jean Vallier (Hagen) with Alfred Cortot conducting.

Beginning that summer and for each summer until 1913, Dalmorès

studied with Marquis de Trabadelo. After his vacation he would

take two lessons every day, one each morning for his voice work

and the other each afternoon for special coaching in his various

roles.

At about this time he also met a person in Brussels who would

greatly benefit his career. As he explained, “I met my

artistic godmother, Mrs. Townsend, the wife of the American

minister to Belgium. She was a charming American woman who interested

me in the idea of learning new languages and singing works in

the languages in which they were written. I went to work hard

and took six lessons a week, three in Italian and three in German.

I had a house at the time on Lago Maggiore so Italian came easily.”

Next, during a third season at Monnaie, he would face eight

productions, with only Siegfried on 3 February (as well

as on 18, 24 April 1903) being a new role. Brünnhilde was

sung by Jeanne Paquot, Hagen by Henri Albers, Mime by Emile

Engel and Fafner by Claude Bourgeois with Alberich a sharing

affair for Maxime Viaud and Henry Dangès as was Erda

for Georgette Bastien and Caroly Rival. Sylvain Dupuis conducted.

In the following season, he was involved in ten different operas,

three being new. On 20 September 1903, he sang as Jean de Leyde

in the first of twenty-one performances of Meyerbeer’sLe

Prophète with Jeanne Gerville-Réache as Fidès,

Pierre d’Assy as Le Comte de Oberthal, Ernest Forgeur

as Jonas and Charles Danlée as Mathisen. Then, on 30

November, he sang Lancelot in the world premiere of Ernest Chausson’s

opera Le Roi Arthus with Jeanne Paquot as Genièvre,

Henri Albers as King Arthus, Arthur François as Mordred

and Forgeur as Lyonnel. Sylvain Dupuis conducted. His third

new role came on 2 April 1904, when he sang Cavaradossi in Tosca

with Jeanne Paquot, Albers as Scarpia and Hippolyte Belhomme

as the Sacristan, Depuis at the helm.

A BEGINNING AT COVENT GARDEN IN 1904

That year the tenor took a major step forward when he joined

the Royal Opera at Covent Garden. He would sing in 1904 and

again in 1905, but would be absent for four years, returning

in 1909, 1910 and 1911 with a repertory dominated by French

opera.

He made his début in Gounod’s Faust on 13

May 1904 and would repeat the role five times during the season.

Marguerite was sung by Suzanne Adams and Nellie Melba while

Méphistophélès was shared by Marcel Journet

and Pol Plançon. Antonio Scotti, Maurice Renaud and Paul

Seveihac portrayed Valentin and Elizabeth Parkina and Christine

Heliane appeared as Siébel. Reviews, however, tended

towards the lukewarm: “M. Dalmorès worked hard

but with all the hard work and the excellent singing there was

a sort of ‘tired’ tone in the atmosphere.”

After another performance, “M. Dalmorès shone to

greatest advantage in the end of the Garden scene.”

For his next challenge on 20 June, he participated in a double

bill, Camille Saint-Saëns’s Hélène

and Massenet’s La Navarraise. In somewhat of a

miracle, Hélène was now to be heard for the first

time in England, as it had been introduced just four months

previously in Monte Carlo. Melba, Kirkby Lunn and Elizabeth

Parkina achieved varying degrees of success, but again, a critic

was negative concerning the tenor: “As the very Parisian

Paris, he provided not a very striking impersonation as the

natural defects of his voice and singing are not compensated

by any great opportunities for histrionic effect.” In

the Massenet opera, he was on familiar ground as Araquil,

appearing with Marguerite (Zina) de Nuovina as Anita, Marcel

Journet as Garrido with Otto Löhse conducting.

In seven performances of Carmen, the role of Don José

was shared by Dalmorès and Gustave Dufriche with Emma

Calvé portraying Carmen with Agnes Nicholls, Hildur Fjord

and Suzanne Adams sharing Micaëla. Escamillo was divided

amongst Antonio Scotti, Pol Plançon and Maurice Renaud.

Luigi Mancinelli conducted.

Massenet’s Salome, described as a ‘Singers’

opera’, was given a single performance on 6 July 1904.

Emma Calvé had been singing the title role with great

success in Paris, so no doubt she was responsible for its presence

here. In addition to Calvé and Dalmorès, Maurice

Renaud appeared as Moriame, Pol Plançon as Phanuel, Kirkby

Lunn as Hesatoade and Charles Gilibert as Caius Petronius with

Otto Löhse conducting. “Dalmorès sang better

as Jean than on any former occasion, and looked very picturesque.”

When he returned to Monnaie, for the 1905-1905 season, he found

business as usual with involvement in nine roles, all ones he

had previously sung. A similar situation occurred in his final

season when he again sang nine roles, but two were new: Berlioz’s

La Damnation de Faust and Bizet’s Carmen.

In the Berlioz on 21 February 1906 as Faust, he sang with Frances

Alda (Marguerite), Albers (Méphistophélès)

and Belhomme (Brander). Dupuis conducted as he did during 25

repeats. Carmen received as many performances with a

Carmen now a mystery, Dalmorès and Leon David sharing

the role of the be-dazzled dragoon, Eugènie Dratz-Barat

as Micaëla and Jean Bourdon and Maurice Decléry,

taking turns as the toreador. Alexandre Lapissidaz conducted.

Unconfirmed reports exist, saying that Dalmorès sang

Jean inLe Jongleur de Notre Dame and indeed there were

twenty-one performances of this opera at Monnaie in 1904. The

only known tenor as Jean was Jean-Philippe Lafitte but Dalmorès

may have participated in one or more performances. Another report

has Dalmorès as Jean in this opera in Chicago in 1914,

but Mary Garden is officially credited with this role in three

performances. Also lacking verification is a report he appeared

in Reyer’s Sigurd.

As for what happened next, he was resting in his Brussels apartment

when he heard a knock at the door. Opening up, he came face-to-face

with the fabled Oscar Hammerstein. The impresario had come to

invite Dalmorès to make his North American debut in New

York as a member of his new Manhattan Opera Company during its

first season. He laid $2,000 in gold on the table but the tenor

was under contract to Monnaie so he was unable to accept this

offer. Furthermore he had just agreed to a four season engagement

in Lisbon. Hammerstein agreed to pay not only for his release

from Monnaie but also from Lisbon, the latter a penalty that

cost him four thousand dollars. And so, Dalmorès happily

accepted Hammerstein’s proposal.

A SECOND SEASON AT COVENT GARDEN IN 1905

For

the present, he continued his allegiance to London. In a pair

of Carmen performances he sang Don José with Emmy

Destinn and Clarence Whitehill and Antonio Scotti dividing Escamillo’s

duties. Pauline Donalda sang Micaëla and André Messager

conducted. Then on 1 June, he helped launch a series of seven

performances of Faust (see photo), sharing the title

role with Vilhelm Herald, with Nellie Melba, Pauline Donalda

and Selma Kurz interpreting Marguerite, Journet and Whitehill

sharing Méphistophélès, Elizabeth Parkina

and Bella Allen doing the same as Siébel with Paul Seveilhac

as Valentin. Messager conducted. In June and July, the tenor

also took on two new challenges, as Roméo in Gounod’s

Roméo et Juliette, which he shared with Herold

during five performances. Selma Kurz and Pauline Donalda shared

in portraying Juliette as did Journet and Vanni-Marcoux in dealing

with Laurent. Elizabeth Parkina was Stéphano. At a Royal

Gala on 5 June, Dalmorès and Selma Kurz previewed Act

II of the opera.

For

the present, he continued his allegiance to London. In a pair

of Carmen performances he sang Don José with Emmy

Destinn and Clarence Whitehill and Antonio Scotti dividing Escamillo’s

duties. Pauline Donalda sang Micaëla and André Messager

conducted. Then on 1 June, he helped launch a series of seven

performances of Faust (see photo), sharing the title

role with Vilhelm Herald, with Nellie Melba, Pauline Donalda

and Selma Kurz interpreting Marguerite, Journet and Whitehill

sharing Méphistophélès, Elizabeth Parkina

and Bella Allen doing the same as Siébel with Paul Seveilhac

as Valentin. Messager conducted. In June and July, the tenor

also took on two new challenges, as Roméo in Gounod’s

Roméo et Juliette, which he shared with Herold

during five performances. Selma Kurz and Pauline Donalda shared

in portraying Juliette as did Journet and Vanni-Marcoux in dealing

with Laurent. Elizabeth Parkina was Stéphano. At a Royal

Gala on 5 June, Dalmorès and Selma Kurz previewed Act

II of the opera.

The other new work, Franco Leone’s L’Oracolo

received a much-heralded world première on 28 June. Mlle.

Donalda and M. Dalmorès were a tuneful pair of lovers

(San Lui and Ah Joe), and Signor Scotti represented the villain

of the piece. Set in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Chim Fen

(Scotti), keeper of a combination gambling house and opium den,

kidnaps a child and murders the young man who tries to rescue

the child, and in turn is killed by the young man’s father

Win Shee (Vanni Marcoux). A blood-soaked tale, conducted by

André Messager, it “was favorably received and

the composer appeared to acknowledge the applause.” Two

more performances followed.

SETS FOOT ON AMERICAN SOIL

With Hammerstein’s contract in his pocket, he gaily boarded

a steamer and headed to the United States. Over the next few

years, he would sing in several cities but his initial allegiance

was to Hammerstein and his Manhattan Opera. Upon its demise

in 1910, he appeared with the Philadelphia Opera, the Chicago

and Boston companies and a conglomerate organization, the Philadelphia-Chicago

Grand Opera Company.

He made his Manhattan Opera début on 7 December 1906

as Faustsinging beautifully with critics

praising his ‘excellent stage presence, manly appearance

and fine acting’. In the words of The Evening World,

he stood, ‘easily in the foremost rank of tenors who have

sung in New York during the past decade. The very attractive

Pauline Donalda sang Marguerite with ‘a clear and sweet

voice. Arimondi’s Méphistophélès

was strong vocally but somewhat weak dramatically.’ Seveilhac,

Donalda’s husband, proved to be a satisfactory Valentin

... but the show was sparsely attended.

A week later on 14 December, Clothilde Bressler-Gianoli was

an earthy, tempestuous Carmen. Her conception of the part was

as an elemental, utterly frank, physical creature with bodily

movements as sinuous as her morals were loose, alluring in its

sheer wickedness. As Don José, Dalmorès, resplendent

in voice and gallant in action, presented an impassioned interpretation

of the hapless dragoon, the victim of Carmen’s wiles and

charms. New York was beginning to recognize him as one of the

finest tenors heard in years.” Ancona, the toreador, sang

with beautiful tone and gave a realistic portrayal, while Pauline

Donalda was convincing and charming as Micaëla. Campanini

conducted. Before the season ended,Carmen would be given

twenty times, the first fifteen with Bressler-Gianoli and the

rest with a fading Emma Calvé. Dalmorès next made

a rare appearance in Italian opera as Manrico in Il Trovatore

on New Year’s Day in 1907 with Giannini Russ as Leonora,

Eleanora de Cisneros as Azucena, Paul Seveilhac as Di Luna with

Luigi Mugnoz as Ferrando with Fernando Tanara as conductor.

In the prevailing view, ‘Dalmorès sang well,’

but the production, as a whole, was not up to standard.

After a second Faust on 14 January 1907, the tenor sang

Turiddu in Cavalleria Rusticana on 1 February with Giannina

Russ, Paul Seveilhac, Emma Giacomini and Gina Severina, conducted

by the ever present Campanini. On 8 February he joined Melba

in Faust.

BEGINS RECORDING FOR VICTOR

At this point in the season, Dalmorès decided to launch

a recording career, such as it was. On 23 February 1907, he

made his first recordings for the Victor Company at their New

York studios at 234 Fifth Avenue. This could have been a trial

effort as neither Don José’s aria from Carmen

nor an aria from Romeo et Juliette were released or retained.

Six days later he was back with basso Marcel Journet to record

duets from Carmen and Faust. This time they were

issued. He took part in eleven recording sessions with Victor,

the final coming on 28 October 1912. In total he made thirty-four

records with twenty-one being released. Included were duets

with Journet and Emma Calvé and the final scene from

Faust with Calvé and Pol Plançon. He also

recorded ‘Vesti la giubba’ from Pagliacci

for Pathé as a trial but apparently nothing came of this

venture.

After his initial attempt to make records, he resumed his season

with Hammerstein during a Gala on 2 March 1907 with Donalda

and Occelier to sing the last act of Faust. Then, at

a matinee performance on 30 March, Emma Calvé appeared

as Santuzza but she had greater success on 10 April as Anita

with Dalmorès as Nicias in Massenet’s La Navarraise.

On 19 April, he helped wind up the season by appearing in a

Gala that honored Campanini, joining Russ and Seveilhac in Act

1, Scene 2 of Il Trovatore.

In 1907, he wrote “I made it a rule, when my season of

opera is over, to spend the summer studying with someone. Recently,

I have been studying German opera under Franz Emmerich in Berlin.

This led to a debut in German that year at the Strasbourg Festival

where, after appearing in La Damnation de Faust under

the direction of Edouard Colonne, I sang Liszt’s Twelfth

Psalm under Felix Mottl. When not at La Monnaie, he was

heard in other European cities such as Frankfurt, Cologne, Berlin,

Vienna and Graz.

Upon arriving in America, he began to learn English- “and

I am studying that language all the time - last Monday evening,

for instance, having nothing to do, I visited the Empire Theatre

and heard Miss Ethel Barrymore’s charming performance

of “Alice Sit-by-the-fire”.

To begin his second season with Hammerstein, Dalmorès

led off on 5 November 1907 as Don José in Carmen

with Clotilde Bressler-Gianoli and Armand Crabbé. Some

critics considered the opera better than the year before, a

circumstance no doubt attributable to the improved orchestra,

since the cast was very much the same. Dalmorès, once

again the Don José, was warmly praised for ‘a well

nigh faultless impersonation, both vocally and dramatically,

Zeppilli the Micaëla, pleased…’ Berlioz’s

version of the story followed the next night when Hammerstein

introduced La Damnation de Faust, but a novelty it was

not, the Metropolitan having produced this opera the previous

season. Renaud as Méphistophélès, was a

lean, cadaverous, hollow-eyed, long-taloned devil while his

victim Marguerite (Jeanne Jomelli) was an adequate singer whose

voice lacked color. Dalmorès as Faust ‘outdid himself’.

After the première of Les Contes d’Hoffmann

on 15 November, Dalmorès reaped his full share of praise,

especially since he was undertaking the role of Hoffmann on

very short notice, replacing an indisposed Léon Cazauran.

Renaud impressed with his versatility and artistry as the four

baritone villains while of Hoffmann’s loves Alice Zeppilli

(Olympia), Jeanne Jomelli (Giulietta) and Fannie Francisca (Antonia),

the critics preferred Zeppilli. Hammerstein viewed the opera

as a sure-fire money-maker, good for endless repetitions.

This was followed on 25 November by the première of Thaïs.

Few reviewed the opera kindly, but Mary Garden was universally

admired with “Dalmorès performing yeoman service,

again replacing Cazauran. As was his wont, he sang with great

beauty of tone and brought the dignity of his splendid physique

to the role of Nicias.”

As the season progressed, he was Araquil in Massenet’s

La Navarraise on 9 December in the first of four renditions.

Then on 31 December, he sang Turiddu in Cavalleria Rusticana

with Giannina Russ, Armand Crabbé (Alfio) and Giuseppina

Giaconia (Lola). As well, he shared the première of Louise

on Friday, January 3, 1908. It was an unequivocal dramatic and

musical triumph as well as ‘an epoch at the Manhattan’.

The principals were inimitable in their roles. Garden, who had

immersed herself in the part of the Parisian grisette, sang

well, even though she was not entirely free of the effects of

a recent illness. Dalmorès was excellent as Julien; Bressler-Gianoli

(the mother) ‘searched with profound insight the depths

of the role and gave a representation exquisite in all details’;

and Gilibert was superb as the Father…”

Repeats of Louise, Carmen and Contes d’Hoffmann

enlivened the balance of the season. After a Louise in

Philadelphia on 26 March, a Gala to close the season on 28 March

included Act II of Faust with Dalmorès, Mary Garden,

Zeppilli and Vittorio Arimondi.

Earlier that day, Hammerstein had broken ground for his Philadelphia

Opera House. When the cornerstone was laid on 25 June, inside

was placed a copper box containing photographs of eleven leading

artists including Charles Dalmorès. Is it still there?

BAYREUTH AND VIENNA HELP TO OPEN DOORS

In 1907 he wrote “I made it a rule, when my season of

opera is over, to spend the summer studying with someone. I

have been studying Wagner under Franz Emmerich, as well as recently

with Cosima and Siegfried Wagner.” “This led to

a debut in German at a Festival in Strasbourg, where, after

appearing in La Damnation de Faust under the direction

of Edouard Colonne, I sang Liszt’s ‘Twelfth Psalm’

under Felix Mottl. After that, I met Cosima and Siegfried Wagner

and it was arranged that I should sing at Bayreuth.”

True to her word, Cosima invited him to come to Bayreuth during

July and August 1908. Upon his arrival, he received further

coaching from conductor Ernest Knoch before making his début

at the Festspielhaus as Lohengrin, sharing the role with Alfred

von Bary, with Katherine Fleischer-Edel (Elsa), Marc Davison

(Telramund), Edyth Walker (Ortrud) and Allan Hinckley (Heinrich)

with Siegfried Wagner conducting. Thus, he became the first

French tenor to tread upon these hallowed boards in a leading

role. Later he would declare, “This opened my way into

ninety German theatres, in any one of which I may sing Lohengrin

at any time. In many I have appeared, not only in Lohengrin,

but in Carmen and Samson, singing the latter works

in French.” In 1909 he would be singing Wagnerian roles

in Boston, Philadelphia and Chicago.

Moving to Vienna, he spent the last two weeks of September there,

and on 17 September 1908, sang Samson with Madame Charles Cahier

as Dalila, Anton Moser as Grand Prêtre and Karl Reich

as Abimelech, repeating the experience on the 22nd.

In between on the 20th, he sang the title role in

Lohengrin with Lucy Weidt as Elsa, Hans Melms as Telramund

and Anna von Mildenburg as Ortrud. He also sang Don José

in Carmen twice, on the 25th with Mme. Cahier,

and on the 28th with Bertha Forster-Lauterer. Grete

Forst was Micaela and Melms Escamillo in both performances.

On 1 October to conclude his visit, he sang a second Lohengrin

with Signe von Rappe as Elsa.

“My holiday I spend in a modest villa of my own on Lake

Maggiore in Italy with my wife, my dogs and my automobile. -

this helps me to learn Italian. I have a brother who sings in

grand opera under the name of Lorrain, and he has a fine tenor

voice. I have had some tragedy too, who has not? My wife became

blind six years ago. Such eyes - and they cannot see.”

With his financial situation improving, he had begun laying

aside funds that would provide for his loved ones, his mother

and wife, in case of any calamity that would affect his voice

or his singing career. Unfortunately in his writings, Dalmorès

never mentioned his wife by name nor did he reveal her ultimate

fate.

On a high, probably envisioning a way to benefit financially,

Dalmorès signed a contract with the Metropolitan Opera

covering the period of 15 November 1908 until 30 April 1909

worth $50,000, double his current income, with a prospect of

four more years with an earning potential of $200,000. Trouble

was, he was still under contract to Hammerstein so a few days

later, regretfully, he notified the Metropolitan that he would

not honor his contract. Immediately the Met countered with a

lawsuit. In the end two years later, Dalmorès lost and

was required to pay the Met $20,000, according to a forfeiture

clause in the contract. Instead, the tenor decided to avoid

the Met collectors by boarding the steamer Potsdam disguised

as a member of the ship’s band. The incident created scandalous

headlines but was his decision really a wise one? He lost thousands.

So he continued with Hammerstein, now showing his true métier

as a star performer in French opera. As the third season got

underway, Dalmorès and Mary Garden appeared on 11 November

1908 in Thaïs, an event witnessed by the New York

Times: ‘Mr. Dalmorès was heard again with great

pleasure and his fine tenor, with the virility of the baritone

quality that makes itself evident from time to time, was again

the object of just admiration. “He sang with splendid

fervour and power, and he makes of a comparatively minor part

of Nicias something of dramatic value.’ Two nights later,

‘As Samson, Dalmorès again offered his superb characterization

of his role, impressing by his diction, vigour, personal appearance,

and magnificent voice.’ He sang this role six times.

Meanwhile in Philadelphia, Hammerstein’s spanking, new

Opera House was due to open on Tuesday, November 17, 1908 with

Bizet’s Carmen. “Never had the city seen

anything like it. An estimated total of 1800 vehicles wound

their way to the opera house, choking the main avenues.”

Of the singers, “Maria Labia was a most attractive Carmen

pictorially but disappointing dramatically. Dalmorès

and Zeppilli were highly praised and De Segurola encored for

his second act aria, sang with authority and ardor.” Two

nights later, with Jeanne Gerville-Réache, Hector Dufranne

and Armand Crabbé, he sang the first of three performances

of Samson et Dalila. Then, on 10 December, he essayed

a third role, Hoffmann in Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffman,

enabling him to romance three lovelies: Alice Zeppilli (Olympia),

Jeanne Espinasse (Giulietta) and Emma Trentini (Antonia) with

Armand Crabbe and Maurice Renaud supplying the villainy.

Returning to New York, the company repeated Offenbach’s

opera on 16 December with essentially the same cast, providing

seven performances overall. On 6 January 1909, however, Dalmorès

began a series of four Pelléas et Mélisandeswith

Mary Garden, Jeanne Gerville Réache as Genéviève,

Hector Dufranne as Golaud and Felix Vieuille as Arkel with Campanini

conducting. Though usually successful in roles he performed,

for The Sun, Dalmorès proved “too vital a figure,

seemingly miscast as the dreamy, shadowy legendary Pelléas”

and was also judged to be not at all familiar with the style

of the opera, in that he seemed uncomfortable in the part. On

12 January, he was back in Philadelphia to repeat Les Contes

d’Hoffmann with Helene Koèlling as Antonia.

When Richard Strauss’s Salome was given its American

Première at the Metropolitan Opera in New York on 22

January 1907, Olive Fremstad was a sleek tigress of a princess,

yet hardly a 15 year old. Giving his reaction, Henry E. Krehbiel

wrote in the New York Tribune: “There is a vast deal of

ugly music in Salome ... music that offends the ears

and rasps the nerves like fiddlestrings played on a coarse file.

There is not a whiff of fresh and healthy air blowing through

it. Salome is the unspeakable; Hérodias is a human hyena;

Hérod a neurasthenic voluptuary…”

So, when Hammerstein’s Manhattan Opera chose to offer

Salome in French on 28 January 1909, it was the most

eagerly anticipated event of the season. Once again the critics

couldn’t stop praising Mary Garden while Dalmorès,

as the neurotic Hérod, gave a lifelike picture of the

Royal voluptuary, his interpretation being ‘truly noble’.

Just fifteen days after the Salome launching in Chicago,

and in the midst of a series of operas there, Dalmorès

brought his role of Hérod to Philadelphia. However, before

that could happen, he and Mary Garden gave the city’s

opera-lovers their version of Pelléas et Mélisande

on the 9th February. Quite different was Strauss’s

opera. When it was announced that Salome would be given,

loud rumblings of discontent were heard and the vituperation

soon exceeded that registered when the opera had been mounted

by the Metropolitan in New York. Enormous crowds gathered both

outside and inside the house. The Public Ledger described it

“the most extraordinary operatic occasion in the history

of the city”. Mary Garden’s characterization was

praised to the skies, her singing less so. Her dance was remarkable

for its grace and voluptuous charm ... through it all she was

a vision of loveliness. Dalmorès, the neurotic Herod,

gave a lifelike picture of the royal voluptuary. Dufranne, the

Prophet, sang and acted impressively while Doria was the able

Hérodias. When Hammerstein presented the opera a second

time on 16 February, the house again was crowded, hundreds not

being able to obtain admission. A third performance on 1 March

was the last. Hammerstein withdrew the opera, preferring “not

to take the risk of being the man who taught Philadelphia anything

it thinks it ought not to know.” Louise was also

performed on March 18th and 23rd with

Mary Garden and Dalmorès together on stage once more.

Finally Dalmorès joined Jeanne Gerville-Reache in Samson

et Dalila on 30 March to complete his season in this city.

When the second spring tour got underway, Dalmorès skipped

Baltimore but was active in Boston.

Hammerstein had plans to presentSalome in Boston but,

when officialdom became fierce in their opposition and when

the Mayor decreed that the good burghers of Boston would not

be corrupted by Hammerstein’s immoral Salome, he

had no choice but to withdraw the opera. Instead, Boston’s

opera fanatics had to be content, seeing and hearing Pelléas

et Mélisande for the first time on 1 April with Dalmorès

and Garden. The next evening he was back as Hoffmann in Les

Contes d’Hoffman with Alice Zeppilli as Olympia and

Giulietta, and Emma Trentini as Antonia. On 5 April, and again

on the 19th, he and Mary Garden sang Louise

with Augusta Doria (La mère) and Charles Gilibert (Le

père).

Following Boston, Dalmorès journeyed to Europe where

he was due to sing at a Covent Garden season but first he traveled

on to Vienna to make a second appearance, leaving Affre and

Fontaine to sing tenor roles in London until he arrived. In

Vienna, on 17 May, Dalmorès joined Lucy Weidt, Mme. Charles

Cahier and Friedrich Weidemann in Aida. Then on 20 May,

he sang Lohengrin, his Elsa being Signe von Rappe and

Bertha Forster-Lauterer on 23 May. A repeat of Aida was

planned on 26 May but Dalmorès was taken ill so to the

rescue raced Theodor Eckert from Brno. Elisa Elizza sang Aida.

When he did reach Covent Garden, he was thrust at short notice

into the part of Radamès on 5 June 1909 but he ‘sang

and acted with immense vigour and conviction and though his

powerful voice was a little hard at times, it was always quite

true in intonation.’ The starry cast included Emmy Destinn

(Aida), Louise Kirkby Lunn (Amneris), Antonio Scotti (Amonasro),

and Vanni Marcoux (Ramfis). Signor Ettore Panizza conducted.

He next appeared on 18 June as Julien in Louise during

its first presentation in English with Louise Edvina as Louise.

On 30 June, he gave his first Samson at Covent Garden and proved

a tower of strength. ‘He indeed both acted and sang superbly

and his reading was noticeable for many clever and original

points. Kirkby Lunn seemed duly inspired by his presence and

was more magnificent than ever, while Jean Bourbon fulfilled

all the requirements of the High Priest.’ Maurice Frigara

conducted.

Five performances of Faust were offered spread over the

season. Dalmorès sang on 6 July with Messrs Fontaine

and Affre attending to the others. In the case of Marguerite,

three sopranos were needed: Louise Edvina, Maria Kousnietzoff

and Martha Symiane. In the Dalmorès appearance, Edmund

Burke was Méphistophélès while Vanni Marcoux

and Marcel Journet were heard on other evenings.

At some point, Dalmorès realized that spending so many

years in orchestral pits observing how singers plied their trade

and having relatively little formal training, he had achieved

his goal of becoming a successful singer primarily by the ‘self-help’

process.

FINALE WITH HAMMERSTEIN IN NEW YORK

Hammerstein’s Manhattan Opera began its final season on

Monday, 8 November 1909 with its first Hérodiade

in New York - seventeen years later than in New Orleans - Massenet

had become as popular in the United States that Manon

was being seen the same evening to open the Metropolitan’s

Brooklyn season. Hammerstein hoped that, as the plot concerned

Salomé, he might duplicate Mary Garden’s tremendous

success in Strauss’s opera the previous season. As Salomé,

Lina Cavalieri startled New York critics with her vocal improvement,

and, as always her extraordinary beauty enchanted everyone.

Dalmorès, as John the Baptist sang as magnificently as

was his wont but wore a costume which ‘scarcely evoked

the image of one who had fed on locusts and wild honey’.

As Hérode, Renaud was intensely dramatic and superb in

song but Gerville-Réache, the Hérodiade, was less

successful in her part. De la Fuente conducted. It had much

perfumed, voluptuous music, including ‘Vision fugitive’.

But it has not reached the Metropolitan, and for obvious reasons

it is not the competent evening’s pastime Massenet guarantees

at his best, and moreover, Strauss’s version of much the

same events, in Salome, has made Massenet’s opera

seem, by comparison, suitable for student performances at a

female academy. With virtually the same cast, the opera was

given three nights later in Philadelphia and in New York on

24 November.

On 17 November 1909, Hammerstein presented the American premiere

of Sapho, the second of three Massenet novelties given

that season, Hérodiade being the first. Sapho

was not the composer at his best. Whatever success it achieved

was due to the forceful psychological drama Mary Garden imparted

to the prostitute Fanny Le Grand. Others in the cast were Dalmorès

(Jean Gaussin), D’Alvarez (Divonne), and Dufranne (Caoudal)

with De la Fuente conducting. It was given as well in Philadelphia

on 20 November.

Moving on, he portrayed Faust on 8 December with Mary

Garden (Marguerite), Jean Vallier (Méphistophélès),

Hector Dufranne (Valentin), and Regina Vicarino as Siébel.

Just prior to Christmas it was especially hectic. On 21 December

Samson et Dalila was given with Dalmorès as Samson,

Jeanne Gerville Réache as Dalila, Hector Dufranne (High

Priest) and Armand Crabbé (Abimelech). Then in Pittsburgh

they performed Sapho on the 23rd. Scurrying

back to New York, they celebrated Christmas Day with an evening

performance of Les Contes d’Hoffmann with Dalmorès

pursuing Emma Trentini as both Olympia and Antonia and especially

Lina Cavalieri as Giulietta. After a couple of days off, the

company roared into action again in Cincinnati with Sapho

on the 28th.

Early in 1910, the Company traveled to Washington where Dalmorès

and Garden sang in Massenet’s Thaïs on 11

January with Renaud as Athanaël and Nicosia at the helm.

Two nights later, still in the nation’s capital, Dalmorès

appeared in Les Contes d’Hoffmann with Emma Trentini

as all three loves while four villains were provided by Giuseppe

de Grazia and Renaud. Then, back in New York, the cast delivered

Offenbach’s opera during a matinee on 15 January with

Maria Duchène as Giulietta the main cast change.

The third Massenet opera, Grisélidis, produced

in New York on 19 January 1910 with Dalmorès as Alain,

Mme. Walter-Villa (Flaminio), Maria Duchène (Bertrade),

Gustave Huberdeau (Devil), Henri Scott (Gondebaud) and Hector

Dufranne (Marquis), drew praise from all quarters. In an un-credited

review, it was stated: “Vocally and dramatically one of

the great triumphs of the night was scored by Charles Dalmorès,

as Alain the shepherd. It is but another indication of a great

artist’s willingness to play what might be called a secondary

part, in order that the production should go on record as a

finished performance. Alain appears only in the Prologue and

the Second Act, but his art and voice united in giving a presentation

that was as remarkable as that of the prima donna in the title

role. The success of the Prologue depends on Alain. The opening

and closing passages are entrusted to him; and great was the

skill and beauty of his work. Not since his debut at this opera

house has Dalmorès been in better voice or form than

at the premiere of Grisélidis.” Then it

was off to Philadelphia for Faust with Dalmorès,

Mary Garden and Huberdeau and Grisélidis.

New Yorkers witnessed the tenor and Gerville-Réache,

on the 28 January enact Samson et Dalila. “The

Samson of Dalmorès stands out as one of the marvelous

impersonations of this operatic era. What is the magic that

enables this wonderful tenor to transform himself into a strong

man, an athlete in physique, and a passion in his singing and

acting that stirs up the people to a frenzy of excitement? He

carried conviction in every move and gesture. The features,

first marked by the strength of the physical and moral giant;

then kindled into the glow of passion as Delilah coos her love

phrases; then on to the terrible suffering in his blindness,

and finally aroused through contrition and prayer to exaltation

and religious fervor and finally back to the physical powers

which enable him to tear down the pillars of the Temple of the

Dragon and destroy his enemies.” After the first act,

Arthur Hammerstein came before the curtain and explained that

Mr. Dalmores had become suddenly afflicted with hoarseness,

and in consequence the indulgence of the assemblage was asked.

It was only in the second act where his voice seemed veiled.

In the prison scene and at the close he sang with his usual

opulence and beauty of tone.”

On 7 February, he played a prominent part in a gala to benefit

flood sufferers in Paris with Mary Garden in Act IV of Roméo

et Juliette and the St. Sulpice scene from Manon.

After a Samson et Dalila in Philadelphia on 12

February, he must have looked forward to romancing the gorgeous

Lina Cavalieri in Carmen back in New York on 19th

February. This was followed by performances of Louise

with Alice Baron on the 23rd and with Mariette Mazarin

during a matinee on the 26th. On the 28th

he was Araquil in La Navarraise with Jeanne Gerville

Réache as Anita, Hector Dufranne as Garrido and Armand

Crabbé as Ramon with De la Fuente conducting. On 5 March,

Mary Garden, Dalmorès, Augusta Doria and Dufranne gave

the first of four performances of Salome. Then on 11

March, he and Garden were heard in Pélleas et Mélisande.

The next evening, this pair was in Philadelphia heading a large

cast in Louise. In New York again they sang in Salome

on the 14th, followed on the 16th byPélleas

et Mélisande. In Philadelphia, after a Faust

with Dalmorès, Garden and Jean Vallier on 19 March, they

provided Pélleas et Mélisande on 22 March.

Returning to New York for a Gala concert on 25th

March, Dalmorès sang Act II of Samson et Dalila

with Gerville-Réache, the chamber scene from Roméo

et Juliette with Mary Garden and the final scene from Faust

with Garden and Huberdeau. The next day he and Mary Garden presented

Debussy’s opera during a matinee before racing to Philadelphia

to participate in a closing Gala that was similar to the night

before except that Augusta Doria appeared as Dalila.

Afterwards on 26 April, Oscar Hammerstein sold his operatic

interests, including the Philadelphia Opera House to the Metropolitan

Opera in New York. The opera house was renamed the Metropolitan

Opera House.

MORE TRIUMPHS AT COVENT GARDEN IN 1910.

That summer Dalmorès relaxed aboard a steamer bound for

England, no doubt thinking n about his coming date at Covent

Garden. “Samson et Dalila was given last night

with two changes in the cast. M. Dalmorès replaced M.

Franz in the part of Samson, and M. Bourbon replaced Mr. Edmund

Burke in that of the High Priest. The French tenor was in fine

voice and he delivered the militant airs in the first act with

splendid tone which was never forced. And in the second act,

he made the duets with Mme. Kirkby Lunn sound beautifully rich

and full. His acting, too, was convincing and effective, so

that altogether he left an excellent impression.” Four

further performances followed.

The performance of Louise on 25 June, the first in English,

impressed. “Passion and character, these are the dominant

notes of all the figures who move across the stage, from the

first appearance of Julien singing in the sunshine of his love

for Louise to the last terrible moment when the old man, deserted

and broken-hearted staggers to the window and shakes his fist

into the night. These two notes were as conspicuous this year

as last in M. Dalmorès’ interpretation of the part

of the poet, and his voice retained its power and freshness

throughout the evening. Mme. Edvina once more made a deliciously

youthful and pathetic figure of Louise.” Louise Bérat

was La mère and Charles Gilibert as Le père with

Maurice Frigara at the podium. The opera was performed seven

times.

/

Faust on 7 July featured “in addition to the charming

Marguerite, Mlle. Kousnietzoff, and the impressive Méphistophélés

of Edmund Burke, the Faust of M. Dalmorès who not only

sings and acts with taste and vigour, but looks the part to

perfection. Mlle. Edna de Lima, who has an agreeable voice,

made quite an effective Siébel.” Overall, five

performances of Faust featured tenors Dalmorès,

Paul Franz and Riccardo Martin, two sopranos, Louise Edvina

and Maria Kousnietzoff as Marguerite, bassos Edmund Burke and

Vanni Marcoux as Méphistophélès, and, as

Siébel, Martha Symiane and Edna de Lima. Campanini and

Panizza shared conducting duties.

In 18 July, he faced a lone new opera in La Habañera,

a Spanish horror piece by Raoul Laparra, in which the evil Ramon

(Jean Bourbon) lusting after his brother Pedro’s beloved,

a luscious Pilar (Hélène Demellier), murders Pedro

(Dalmorès), afterwards sqearing to all that he will avenge

his brother’s death. Haunted by the ghost of Pedro, Ramon

confesses his crime to Pilar who drops dead at the news. The

grisly tale dominated the music that set it: harsh, bitter with

delineative force. Maurice Frigara conducted.

A WINDY CITY RECRUIT

Upon returning to the USA with the Manhattan Opera no more,

Dalmorès had boarded a train and headed west to sing

with the newly-created Chicago Grand Opera Company. During seven

seasons he would sing French opera almost exclusively except

for the occasional offering of Wagner. Dalmorès made

his initial appearance on 9 November 1910 as Julien inLouisewith

Mary Garden, Clotilde Bressler-Gianoli (La mère) and

Hector Dufranne (Le père). The stage must have staggered

under the burden of forty-five bodies all vying for Campanini’s

guidance.

After a second Louise on the 14th, he was

back on stage the next night to portray Don José to Marguerite

Sylva’s Carmen with Alice Zeppilli (Micaëla)

and Armand Crabbé (Escamillo) with steady Campanini at

the podium. He returned on the 19th as Faust

with Lillian Grenville (Marguerite), Vittorio Arimondi (Méphistophélès)

and Crabbé (Valentin). Marcel Charlier wielded his baton.

Then, after a third Louise came the season’s

eagerly-awaited ‘pièce de résistance’.

After what had transpired in New York, when Salome was

performed in Chicago, the audience on the night of 28 January

1909 may have braced themselves, anticipating a similar outcome.

Mary Garden beforehand confidently declared “Chicago’s

is going to love Salome.” Not so. The audience was shocked

to its socks. They hissed. They screamed. Despite talk of cancellation,

a second performance took place on the 28th. What

offended most people was the reality with which Mary Garden

portrayed Salome’s lust for the prophet John and particularly

her perverted ecstasy with the head. A third performance was

cancelled.

The reaction infuriated a number of artists. Charles Dalmorès,

who had sung the role of Hérod, led the charge: “It

is horrible. Chicago will be the laughing stock of Europe. It

puts you back artistically fifty years … why, in Europe

we talk about America as the land of the free. You are not.”

To another reporter, he said, “Berlin and Vienna will

laugh when they hear this. They will say, “The great Chicago.

What is it? Still a manufacturing city without a true love of

art?”

When the smoke cleared, Dalmorès returned to the stage

on 6 December as Nicias in Thaïs with Mary Garden,

Renaud and Huberdeau. Then, as a change of pace, he tackled

an Italian role on the 11th singing Turiddu in Cavalleria

Rusticana with Marguerite Sylva (Santuzza), William Beck

(Silvio) and Tina di Angelo (Lola) with Parelli conducting.

On 15 December he essayed his last new role of the season, the

title character in Offenbach’s Les Contes d’Hoffmann

with Sylva (Giulietta), Lillian Grenville (Antonia) and Alice

Zeppilli (Olympia) with Maurice Renaud as an evil trio, Coppelius,

Dapertutto and Dr. Miracle. At a late season gala on 16 January,

Acts I and II of Offenbach’s opera were given with Dalmorès

portraying Hoffmann. Though the season ended with a deficit

of $10,000, it was deemed, overall, to have been a distinct

success.

PHILADELPHIA-CHICAGO GRAND OPERA IS FORMED

However management was feeling the pinch. The ten week season

was too short to finance production of the caliber of opera

it sought so a plan evolved that would create a new company

to provide opera in Philadelphia, New York and other eastern

cities following the Chicago season. For the first three years

this organization was known as the Chicago-Philadelphia Grand

Opera Company (or Philadelphia-Chicago when it played in Philadelphia),

since guarantor support came from both cities. And so, here

it will be known as ‘P-C.’ In the next few years,

Dalmorès would fulfill an amazing schedule.

Quickly off the mark, the new company performed Thaïs

in Philadelphia on 21 January 1911 with Mary Garden, Dalmorès

as Nicias, Maurice Renaud as Athanaël and Gustave Huberdeau

as Palémon with Campanini conducting. Three nights later

in New York City, the same principals gave the opera in the

Metropolitan Opera House. Returning to Philadelphia on the 28

January, P-C presented Louise with Mary Garden, Dalmorès,

Clotilde Bressler-Gianoli as La mère and Hector Dufranne

as Le père. This artistic ping-pong continued three days

later when Louise was given in New York and Thaïs

was repeated in Philadelphia on 1 February.

Checking his schedule, Dalmorès slipped away to make

his début two nights later with the Boston Opera as Faust

with Mary Garden and fellow Frenchmen, Léon Rothier and

conductor Caplet. Rothier’s rich voice gave Méphistophélès

a songful aspect. Philip Hale of the Herald “acknowledged

the tenor’s artistic qualities, and pronounced him manly,

chivalric, a tender lover as well, picturesquely costumed without

disfiguring whiskerage. His consummate skill both in amorous

and heroic measures showed song and action to be inseparable.”

Another critic spoke of Dalmorès as a figure of romance,

with a tenor’s grace. Rounding out the cast were Pierre

Letol (Valentin) and Jeska Swartz (Siébel).

Returning to Philadelphia, he essayed the title role in Faust

on the 8 February with Frances Alda as Marguerite, Gustave Huberdeau

as Méphistophélès, Armand Crabbé

as Valentin and Tina di Angelo as Siébel. Marcel Charlier

conducted. Then, they packed their bags and headed to New York

to present Les Contes d’Hoffmann on the 14th.

Two nights later, everyone went to Baltimore where the tenor

sang Don José in Carmen with Marguerite Sylva

and Alice Zeppilli as Micaëla.

Then, it was back to Philadelphia for Les Contes d’Hoffmann

on 1st and 10th of March with Dalmorès

as Hoffmann. This was followed by Quo Vadis, a five act

opera by Jean Nouguès, based on a novel by Sienkiewicz

which received its US Premiere on 25 March with Dalmorès

as Vinicius, Alice Zeppilli (Lygie), Lillian Grenville (Eunice),

Vittorio Arimondi (Nero), Maurice Renaud (Petrone), conducted

by Campanini. During a season-ending Gala on 1 April, Dalmorès,

Garden and Dufranne presented Act II of Thaïs.

A VISIT TO PARIS

That summer, Dalmorès visited L’Opéra de

Paris on 16 June 1911 to sing the title role in Siegfried

during that city’s first Ring cycle with Louise Grandjean

as Brünnhilde, Delmas (Wotan) and Lyse Charny (Erda) with

Felix Weingartner conducting. Then, as he reported: “After

Paris, I shall go to my new home on Switzerland, from where

I can motor to Aix-les-Bains in two hours. Miss Garden and I

have been engaged for four performances at that watering place

in ‘Carmen’ and Isadore de Lara’s ‘Messaline.’

Miss Garden has not yet been heard in either of these parts.

In the fall, I shall sing in German cities in German and after

that I return to America.”

A LAST HURRAH AT COVENT GARDEN

That summer he bade farewell to fans at Covent Garden with four

familiar French roles. He led off in Samson et Dalila,

sharing the role of Samson with Paul Franz. The series of seven

performances began on 24 April with Kirkby Lunn (Dalila), Edmund

Burke (Grand Prêtre). In Louise, again sharing

with Franz, he sang Julien with Louise Edvina and Vanni Marcoux.

In a lone Carmen on 6 May, he sang Don José with

Kirkby Lunn, Lalla Miranda (Micaëla) and Alexis Ghasnes

(Escamillo). Finally Faust performances on 23 May and

2 June were shared by Dalmorès and François Darmel

with Nellie Melba (Marguerite), Edmund Burke (Méphistophélès),

Alexis Ghasnes (Valentin) and Tina de Angelo (Siébel).

Percy Pitt conducted all of the performances.

ACTION IN CHICAGO, PHILADELPHIA, BOSTON, NEW YORK ET

AL

Later,

with P-C in Philadelphia, he experienced a hectic November.

With Mary Garden he headlined Carmen on 3 November with

Hector Dufranne and Alice Zeppilli, following this on the 8th

with Samson with Jeanne Gerville-Réache, Hector Dufranne

and Armand Crabbé. Next, he sang Siegmund, presumably

in German, in a performance of Die Walküre, (see

left) with Jane Osborn-Hannah as Sieglinde, Olive Fremstad as

Brünnhilde, Henri Scott as Hunding, Clarence Whitehill

as Wotan and Jeanne Gerville-Réache as Fricka with Szendrei

conducting. After Carmen on the 13th with

the previous artists except Huberdeau who now filled the shoes

of Escamillo, the company transported themselves to Baltimore

to present Samson et Dalila on the 16th again

with Dalmorès, Gerville-Réache and Huberdeau.

And so, his busy session with P-C concluded.

Later,

with P-C in Philadelphia, he experienced a hectic November.

With Mary Garden he headlined Carmen on 3 November with

Hector Dufranne and Alice Zeppilli, following this on the 8th

with Samson with Jeanne Gerville-Réache, Hector Dufranne

and Armand Crabbé. Next, he sang Siegmund, presumably

in German, in a performance of Die Walküre, (see

left) with Jane Osborn-Hannah as Sieglinde, Olive Fremstad as

Brünnhilde, Henri Scott as Hunding, Clarence Whitehill

as Wotan and Jeanne Gerville-Réache as Fricka with Szendrei

conducting. After Carmen on the 13th with

the previous artists except Huberdeau who now filled the shoes

of Escamillo, the company transported themselves to Baltimore

to present Samson et Dalila on the 16th again

with Dalmorès, Gerville-Réache and Huberdeau.

And so, his busy session with P-C concluded.

With barely enough time to catch their breath, he and his mates

made their way to Chicago where they opened on 22 November 1911

with a lackluster Samson et Dalila. The Saint-Saëns’s

work had been given often in Chicago as an oratorio but never

as an opera. Dalmorès was Samson with Jeanne Gerville-Réache

as Dalila, Hector Dufranne, Armand Crabbé and Gustav

Huberdeau with Campanini conducting. Though poorly lit, poorly

staged and with a falling temple that would scarcely harm anyone,

the audience was in a forgiving mood and showed enthusiasm for

everything they saw and heard.

The next night in Carmen he was Don José with

Mary Garden, Dufranne as Escamillo and Alice Zeppilli as Micaëla.

On 29 November he portrayed Nicias in Thaïs with

Garden, Dufranne and Huberdeau. During a busy December, he joined

Maggie Teyte in a matinee of Faust on the 16th

with Huberdeau as Méphistophélès, Crabbé

as Valentin and Marta Wittkowska as Siébel. Nouguès’

Quo Vadis was given for the first time in Chicago on

19 December with Dalmorès, Maggie Teyte, Alice Zeppilli

and Clarence Whitehill.

That season the company presented its first operas in German,

all by Richard Wagner with Dalmorès a participant in

all three. On 21 December, he was Siegmund in Die Walküre

with Minnie Saltzman-Stevens as Brünnhilde, Ernestine Schumann-Heink

as Fricka, Jane Osborn-Hannah as Sieglinde, Henri Scott as Hunding

and Whitehill as Wotan. Alfred Szendrei conducted. Next, after

a Christmas Day Hoffmann, he sang Lohengrin on 2 January

with Carolina White (Elsa), Gustave Huberdeau (King Henry),

Marta Wittkowska (Ortrud) and Clarence Whitehill (Telramund).

Then, after a Gala on 18 January in which he and Jeanne Gerville-Réache

sang Act II of Samson et Dalila, Dalmorès took

on Tristan in two performances of Wagner’s Tristan

und Isolde with Isolde sung by Olive Fremstad on 26 January

and by Minnie Saltzman-Stevens on 1 February. Twenty-three year

old Friedrich Schorr appeared as the Steersman.

At the close of the Chicago season with P-C, he wended his way

to New York to sing on 13 February 1912 with Mary Garden in

Carmen with Maurice Renaud as Escamillo and Alice Zeppilli

as Micaëla. The previous Die Walküre in Baltimore

must have been a success as a repeat was given in this city

on 15 February with the same cast except for Margarete Matzenauer

who sang Brünnhilde.

The next day everyone returned to Philadelphia to present Les

Contes d’Hoffmann with Dalmorès and his usual

compatriots, ZeppilIi, White, Renaud and Crabbé, as well

as Marcel Charlier the conductor. Then, on 19 February, the

company offered a rarity, an Italian opera, Cavalleria Rusticana

with Dalmorès as Turiddu, Berta Morena as Santuzza, Alfredo

Costa as Alfio, Frances Ingram as Lola and Giuseppina Giaconia

as Mamma Lucia with Attilio Parelli conducting. A performance

of Thaïs on 21 February had the usual protagonists

Garden, Dalmorès, Renaud and Huberdeau. Two nights later,

the company gave Philadelphia’s Wagnerians a treat, Tristan

und Isolde with Dalmorès as Tristan, Minnie Saltzmann-Stevens

as Isolde, Eleanor de Cisneros as Brangäne, Clarence Whitehill

as Kurvenal, Henri Scott as King Marke and Armand Crabbé

as Melot with Campanini conducting. Samson et Dalila

followed on 26 February with Dalmorès, Jeanne Gerville-Réache,

Maurice Renaud and Armand Crabbé. Then, everyone entrained

for Baltimore to deliver a performance of Lohengrin on

29 February with Dalmorès in the title role. The identity

of his Elsa is a mystery but Eleanora de Cisneros sang Ortrud,

Henri Scott appeared as Heinrich and Clarence Whitehill was

Telramund with Szendrei conducting. Back in Philadelphia, the

tenor took part in Faust on 2 March with Garden and in

Les Contes d’Hoffmann on 6 March with Jenny Dufau,

Carolina White and Alice Zeppilli. Next, the company presented

Die Walküre on 9 March with Dalmorès as Siegmund,

Jane Osborn-Hannah as Sieglinde and Margaret Matzenauer as Brünnhilde.

At this point P-C embarked on a tour that began in New York

on 12 March with a performance of Thais with Dalmorès

and regulars. Moving over to Baltimore, he sang in Carmen

on 14 March with Mary Garden. Then, back in Philadelphia on

20 March, they presented Louise with Garden, Dalmorès,

Bérat and Dufranne. Revisiting Baltimore, they performed

Tristan und Isolde on 22 March with Johanna Gadski as

Isolde, Dalmorès as Tristan, Eleanora de Cisneros as

Brangäne, Clarence Whitehill as Kurvenal and Henri Scott

as King Marke. Finally, in Washington on 26 March, the company

performed Louise with the usual foursome: Garden, Dalmorès,

Bérat and Dufranne.

The next evening the tenor turned up in Boston for a Carmen

with Garden and Dufranne: “somewhat less attention focused

on the José of Dalmorès…new to Boston. In

his only appearance of the season, the tenor seemed tired, with

little tone at his command. Consequently he sought to compensate

by declaiming whole passages.”

That autumn with P-C in Baltimore on 1 November, Dalmorès

sang in Carmen with Maria Gay, Armand Crabbé and

Jenny Dufau. Upon returning to Philadelphia, they repeated the

opera on the 9th. Then, on 20 November with Campanini

conducting, P-C presented Tristan und Isolde with the

Baltimore cast except for Lillian Nordica who sang Isolde. Then

back in the Windy City of Chicago, he sang in a matinee Carmen

on 27 November with Maria Gay as the tantalizing gypsy, Hector

Dufranne as Escamillo, Jenny Dufau as Mercédés

and Henri Scott as Zuniga with Marcel Charlier conducting.

He then visited Boston to appear in Puccini’s Tosca

on 2 December 1912. “Dalmorès sang the role of

Cavaradossi only once in Boston, but left an unforgettable impression,

romantic Byronic, virile, he sang with surprising freshness,

and with due intensity - broken by the fashionable sobs, - and

with a new and stirring tang of baritone quality. He was, in

short, manlike and not tenor-like.” Mary Garden was Tosca

with Vanni Marcoux as Scarpia and Hector Dufranne the Sacristan.

He also joined Garden and Marcoux, in Thaïs on 7

December: “Dalmorès complimented the other two

with his striking portrait of the voluptuary Nicias and his

skill in singing.” André Caplet conducted both

operas.

Returning to Chicago on 12 December, he sang in Les Contes

d’Hoffmann with Jenny Dufau (Olympia), Marie Cavan

(Giulietta) and Edna Darch (Antonia), with Hector Dufranne (Coppelius),

Armand Crabbé (Dapertutto) and Gustave Huberdeau (Dr.

Miracle), with Charlier conducting. For his next challenge on

16 December, he sang Jean in Hérodiade with Eleanora

de Cisneros (Hérodiade), Carolina White (Salomé),

Georges Mascal (Hérode), and Gustave Huberdeau (Phanuel),

Charlier again guiding matters. Maestro Campanini was in charge

when Tristan und Isolde was given on the 19th

with Dalmorès as Tristan, Lillian Nordica (Isolde), Henri

Scott (King Marke), Clarence Whitehill (Kurvenal) and Ernestine

Schumann-Heink (Brangäne). After another Hérodiade

the next evening, the tenor was back to sing Wilhelm Meister

in Mignon with Maggie Teyte in the title role, Jenny

Dufau (Philine), Gustave Huberdeau (Lothario) and Ruby Heyl

(Fréderic) with Charlier conducting. In action again

on 26 December, he was Julien in Louise with Mary Garden,

Louise Bérat (La mère) and Hector Dufranne (Le

père) with Campanini conducting.

After singing in Hérodiade on New Year’s

Eve, Dalmorès reappeared on 3 January as Siegmund in

Die Walküre with Minnie Saltzmann-Stevens (Sieglinde),

Julia Claussen (Brünnhilde), Ernestine Schumann-Heink (Fricka),

Henri Scott (Hunding) and Clarence Whitehill (Wotan) with Arnold

Winternitz conducting. After repeats of Louise on 6 January,

Mignon on the 11th and Carmen on the 13th,

he joined Garden for a Tosca on the 17th with

a second performance on the 22nd. Mario Sammarco

was Scarpia, Constantin Nicolay, the Sacristan and Vittorio

Trevisan as Angelotti with Campanini conducting.

When Riccardo Zandonai’s Conchita was given in

Chicago on 30 January 1913, it revealed that Victorian moral

standards still prevailed in this city. It concerns “a

Carmen-like worker in a cigar factory in Seville, who breaks

the monotony of her life by singing and dancing. A suitor seeks

her favor by bribing her mother. Most Chicagoans found it coarse

and shocking”. Dalmorès, in his last offering of

the season, took part as Don Mateo with Tarquinia Tarquini as

Conchita with Edna Darch as Dolores, Ruby Heyl as Ruffina, Louise

Bérat as Conchita’s mother and Rosina Galli as

the dancer La Gallega.

On 6 February with P-C, Dalmorès and the rest of the

Chicago cast, except for Helen Stanley who now sang Dolores,

gave Conchita in Philadelphia. Five nights later New

York opera-lovers experienced the opera. Then, in Philadelphia,

Thaïs was performed by the regular cast headed by

Mary Garden and Dalmorès on 15 February, and in New York

on the 18th. The next evening the company repeated

Conchita in Philadelphia.

Dalmorès next found himself sharing another American

première when, in a joint effort of the Chicago Grand

Opera and P-C, William (Wilhelm) Kienzl’s Le Ranz des

Vaches was produced, with the first performance being in

Philadelphia on 21 February 1913. A tale of the French Revolution,

originally known as Der Kuhreigen, it was now being sung

in French. Dalmorès headed the large cast as Primus Thaller

with Constantin Nicolay (Louise XII), Eleanor de Cisneros (Marion)

and Gustave Huberdeau (Marquis Massimelle). The opera was repeated

in Philadelphia on 24 February and at the Metropolitan Opera

in New York the following night.

In the summer of 1913, Dalmorès took to the high seas

once again in order to sing at L’Opéra de Paris.

Here he portrayed Hérod in Salome with Mary Garden

(Salome), Hector Dufranne (Jochanaan) and Mme. Dubois-Lauger

(likely as Hérodias), conducted by André Messager.

In a second performance, Maria Labia appeared as Salome. He

also sang Siegfried in Die Götterdämmerung.

Both operas were given in French.

Back in the USA, he showed up in Chicago to sing with the Grand

Opera during its 1913-1914 Season. He appeared initially on

27 November as Siegmund in Die Walküre with Jane

Osborn-Hannah (Sieglinde), Julia Claussen (Brünnhilde),

Margaret Keyes (Fricka), Henri Scott (Hunding) and Clarence

Whitehill (Wotan) with Arnold Winternitz conducting. He next

flexed his muscles as Samson on 2 December with Julia Claussen

as Dalila, Hector Dufranne as High Priest), Armand Crabbé

as Abimelech and Gustave Huberdeau as the Old Hebrew. His effort

drew this reaction: “If that artist is much less notable

- vocally speaking - in Wagnerian music drama than he ought

to be, he is everything that is effective in the music of composers

whose native land is also his. There were, perhaps, occasions

when the tenor was over heroic in his production of tone, but

we will concede gladly his yearning for as much as possible

of his vocal commodities.

Next on 9 December, it was Chicago’s turn to experience

Le Ranz des Vaches with Dalmorès as Primus Thaller

and Martha Winternitz-Dorda assuming the role of Blanchefleur

amongst other changes. The Tribune liked its old-fashioned theme:

“The plan turns a virtue we are not sufficiently advanced

to despise - the love of home. Such words as decadent, degenerate,

neurotic, perverse, cacophonous, discordant, uncouth, and ugly,

may be given a well earned rest, while it attempted to praise

in old-fashioned phrase the homely virtues of romance and sentiment

and graceful song.” Arnold Winternitz conducted. Two nights

later he was in action as Jean in Hérodiade, finding

that it gained a more positive reaction than previously. He

sang with Julia Claussen as Hérodiade, Carolina White

as Salomé, Armand Crabbé as Hérode and

Gustave Huberdeau as Phanuel with Charlier conducting. Coming

soon after a tawdry Conchita, a review began: “Far

less objectionable, although based on the Salome theme,

was Massenet’s Hérodiade, considered by

many the most brilliant premiere of the season … the stage

picture was rich and colorful. Massenet’s approach to

the subject, of course, is quite different from that of Strauss.

In this version, Salome’s love for John the Baptist is

much nobler. Rather than dancing for his head out of lust, she

tries to save him from execution.”

After appearing again as Samson on 17 December, he took to the

stage on 26 December to join a mighty presence in Titta Ruffo

when he sang Athanaël in Thaïs with Mary Garden

and Dalmorès as Nicias. Then, after a repeat of Le

Ranz des Vaches, he again assumed the role of Siegmund in

Die Walküre with the earlier cast except for Minnie

Saltzmann-Stevens (Sieglinde) and Ernestine Schumann-Heink (Fricka).

During a matinee on 10 January, he repeated in Thaïs,

now with Dufranne as Athanaël. On the following evening,

after fifteen full orchestra rehearsals, Wagner’s Parsifal

was unveiled with Dalmorès in the title role, Minnie

Saltzmann-Stevens as Kundry with Clarence Whitehill (Amfortas),

Henri Scott (Titurel), Allan Hinckley (Gurnemanz), Hector Dufranne

(Klingsor) and Rosa Raisa as a flower maiden. Campanini conducted.

Afterwards, Dalmorès slipped away to Boston for a last

visit on 14 January as Julien in Louise with Louise Edvina,

Margarete D’Alvarez and Vanni Marcoux. Returning to Chicago,

he sang in Louise on 22 January with Garden, Bérat

and Dufranne, in repeats of Thaïs andDie Walküre,

followed by Hoffmann on 29 January with Florence Macbeth (Olympia),

Carolina White (Giulietta) and petite Jenny Dufau (Antonia).

Finally, during a Gala on 30 January, he joined Claussen and

Huberdeau in Act II of Samson et Dalila.

Then, re-joining P-C in New York on 10 February, he sang in

Louise with Garden, Louise and Dufranne. Returning to

Philadelphia the next day, Dalmorès sang in Hérodiade

with Carolina White, Julia Claussen, Armand Crabbé and

Gustave Huberdeau. Then everyone made haste to Baltimore

to give Die Walküre on 13 February with Dalmorès

as Siegmund, Jane Osborn-Hannah (Sieglinde), Minnie Saltzaman-Stevens

(Brünnhilde), Allan Hinckley (Wotan), Clarence Whitehill

(Hunding) and Julia Claussen (Fricka). Arnold Winternitz conducted.

Back in Philadelphia, lighter fare awaited on 16 February, an

abbreviated version of Les Contes d’Hoffman with

Dalmorès, Florence Macbeth, Alice Zeppilli and Desiré

Défrére. This was followed by Louise, Les

Contes d’Hoffmann in Baltmore and Tosca back

in Philadelphia with the tenor as Cavaradossi, Alice Zeppilli

(Tosca), Giovanni Polese (Scarpia), Constantin Nicolay (Angelotti),

and Vittorio Trevisan (Sacristan) with Attilo Parelli conducting.

Then, as his final performance with P-C, Dalmorès sang

Agamennone in Cassandra by Vittorio Gnecchi in Philadelphia

on 26 February 1914 with Julia Claussen (Cassandra), Giovanni