|

|

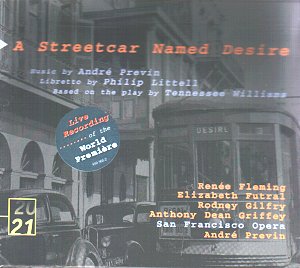

Elia Kazan’ film version of Tennessee William’s play, A Streetcar

Named Desire, was made in 1951. It captured Oscars for Vivien Leigh (Blanche)

Kim Hunter (Stella) and Karl Malden (Mitch) and Oscar nominations for Tennessee

Williams, himself as screenplay writer; director Kazan; and Marlon Brando

(Stanley); and, of course, Alex North. Alex North’s ground-breaking,

jazz-based score is justly celebrated. Therefore, with André

Previn’s considerable experience of film music (he worked on more than

40 films between 1949 and 1973), this recording is of considerable interest

to the serious student of film music. Commissioned by and for the San Francisco

Opera, this is Previn’s first opera. He has, however, accumulated

considerable experience in writing music for the stage. In 1969, he wrote

Coco – a musical for Broadway and, in 1974, another musical for

the London stage, The Good Companions. He also wrote, in collaboration

with Tom Stoppard, Every Good Boy Deserves Favor, a work for

actors and orchestra that was premiered by the Royal Shakespeare Company

and the London Symphony Orchestra in 1976. [Many film enthusiasts will recall

that Claire Bloom made a memorable Blanche on the London stage.]

Previn’s music is essentially more ‘classical’ than the score

composed by Alex North but the jazz influences are nonetheless very apparent

in creating the necessary atmosphere of hopeless degradation and sleazy madness.

Previn says: "Everyone knows that I’ve played a lot of jazz in my lifetime,

so people are bound to say that there is a jazz influence in the harmonies

or the rhythmic patterns. I like to quote Aaron Copland who replied to questions

about jazz in his work by saying, ‘I didn’t grow up in a vacuum.’

I did not set out to write a jazz-influenced score, but I didn’t set

out not to do so either." Previn commented that he also decided to stick

closely to the speech patterns. Many singers have noted the musicality of

Tennessee Williams’s writing.

The opera is, of course, dominated from the start by the character of Blanche

DuBois, and Renée Fleming is very compelling. At the start of the

opera, she arrives in New Orleans to stay with her younger sister, Stella,

who lives in a cramped apartment with her brutal husband Stanley Kowalski

(made famous by the moody magnificent Brando). Blanche berates Stella for

living in such squalor, graphically portrayed in the orchestra. Later, putting

on her airs and graces, Blanche sings of her former genteel existence that

has been shattered by impoverishment caused by relations dying and leaving

nothing. Previn’s sleazy jazz figures and almost ghoulish accompaniment

tells us a different story, however, one of depravity, sex and booze, that

becomes only too clear in Act III. As Blanche gazes at herself in the mirror,

Previn allows her some sympathy and pathos. When, in Act II, she sings

‘Soft people have got to shimmer and glow’, he protects her with

soft-focus music that is almost Delius-like, warm and impressionistic, before

a few intrusive concluding bars remind us of Blanche’s self-delusion.

Later in the same Act, as Blanche recalls the tragedy of her first love and

marriage to a homosexual who later shot himself, the music becomes increasingly

hysterical distorted and grotesque. Blanche only feels secure in her dream

world as she tells Mitch in her ACT III aria "Real! Who wants real?…I

want magic!" As Previn says, "This aria is sultry and torpid and you can

feel the heat and humidity, as well as understand Blanche’s desperation

and her special grace." In Act III after Stanley has raped her, off-stage,

to a most gritty, evocative, three-minute Interlude, Blanche descends into

madness. Her final, poignant aria ‘I can smell the sea air’ is

very moving, as is her last line as she is led away by the doctor, ‘Whoever

you are, I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.’

Rodney Gilfrey as Stanley cannot displace the Brando image, but that is not

to say that Gilfrey fails to convey the complexities of his character: ignorant,

insensitive and brutal but also tender and vulnerable. The scene in which

he opens Stella’s eyes to Blanche’s delusions as he ransacks

Blanache’s trunk is sardonic and vicious enough he makes the Act III

denouement with Blanche before he rapes her quite riveting. Anthony Dean

Griffey is a sensitive Mitch, mother’s boy and too weak to make a

satisfactory saviour for Blanche. His Act II aria, ‘I’m not a

boy…’ shows us his humble humanity but also his own romantic

self-delusion. Self-delusion is a character trait that is shared by the otherwise

sensible Stella, splendidly portrayed by Elizabeth Futral. Stella can forgive

the beating that Stanley has inflicted on her and cradle him like a lost

child afterwards when he has sobered sufficiently to be remorseful.

’Not a brilliant success, the unrelenting decadent harrowing story and

theme tend to grind the production down, but it is certainly a most dramatic

and intensely musical experience.

Reviewer

Ian Lace

|

Reviewer

Ian Lace

|