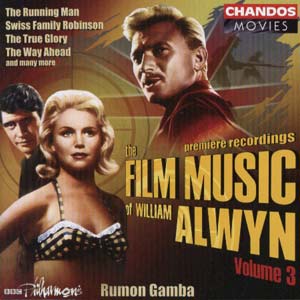

The Film Music of William Alwyn

Music composed by William Alwyn

Music from: The Magic Box, The Million Pound Note, The Way Ahead, Swiss Family Robinson, The Rocking Horse Winner, Geordie, The Cure for Love, Penn of Pennsylvania, The True Glory, The Running Man

Available on CHANDOS (CHAN 10349)

Running Time: 77:49

Crotchet Amazon UK Amazon US

Chandos’s generously-filled third volume of William Alwyn’s film music kicks off with a 15-minute, six-movement suite from the 1951 film, The Magic Box produced for the Festival of Britain celebrations of that year and celebrating the life and career of William Friese-Green (Robert Donat) an early pioneer who perfected the art of colour photography and the moving image. The suite opens with an Elgar/Walton-like imposing theme. The movements that follow charts the relationship between Friese-Greene and his sweetheart, Helena, first in tender tones (reminiscent of Elgar in salon, Salut d’amour mode) then after marriage increasingly fractious as the inventor becomes more and more obsessive of his work. There is wit in the form of a polka underscoring Willie’s first attempts at portraiture, then for ‘Willie Goes to London’ there are more witty cameos as the Friese-Greene’s taste life in the capital. ‘Willie and Edith introduces an attractive ‘Edwardian’ waltz and the final movement recalls the pride of the opening. Gamba and the BBC Philharmonic perform this charming music with style and sensitivity to its period.

Much in the same style and period, there follows William Alwyn’s glittering Waltz The Million Pound Note (1953), based on the story by Mark Twain and starring Gregory Peck. The Cure For Love (1948) has a softer mistily-dream-like waltz for piano and orchestra. Then from the ballroom to the drill square and Alwyn’s stirring march from The Way Ahead (1944) which is not without some sly, sardonic humour surely pointing fun at square bashing and the rough life of army recruits. Another war-time march from The True Glory (1944-45) is stirring in the fashion of Eric Coates and Bliss.

Another suite, some 9 minutes longs follows, from Swiss Family Robinson (1960) and it marked the third collaboration between Alwyn and Disney. The opening movement is a vivid evocation of a vicious storm at sea and the shipwreck of the Robinsons. The other music is playful as the children make acquaintance with all the animal characters on the island, and wistful and poignant with a sweetly sentimental violin solo to illustrate harmonious family life and the warmth between the parents (John Mills and Dorothy McGuire)

A note of menace is introduced in dark, bleak, grotesque nightmare music Paul’s Last Ride from The Rocking Horse Winner (1949) in which a young boy rides his rocking horse in unbridled frenzy to predict the winner of the Derby. The 1941 film Penn of Pennsylvania as might be imagined drew a musical pastiche of elegance and refinement the movement titles reflecting after the Title Music: ‘Banqueting Scene’ in Baroque dignity and splendour with a cheeky little gigue-like aside, wistful and sentimental ‘Love Music’ working up to a passionate climax, The King’s Portrait’ is another witty little Baroque cameo – gentle fun poked at the Royal dignity. ‘Finale’ has pride and pomp of a new state of America.

The Running Man (1962) produced and directed by carol Reed was Alwyn’s last score. It starred Laurence Harvey as a pilot who fakes his own death to collect the insurance money. The music, in four movements is dramatic and tense. ‘Glider Flight’ is evocative of the thrill and fun of gliding on thermals (the music nicely evoking twists and turns and lifts and falls) over sunny landscapes. ‘Stella and Stephen’ begins quietly with a Spanish-style guitar strumming before a sudden string chord introduces disquiet on tremolando strings and rasping trumpets, dark Spanish rhythms pervading.

‘Spanish Gipsy Wedding’ is delightful and relaxing Spanish music in the style of Chabrier.

The most substantial suite (17 minutes) is that for the 1955 film Geordie Much of the material is derived from Scottish folk tunes for this story of a young Scottish athlete who triumphs at the Melbourne Olympic Games. The Main Titles music moves from broad march-like statements to a broad romantic melody. ‘Watching the Eagles’ is a vivid evocation of the magnificent bird in flight against a Scottish landscape. ‘The Samson Way’ is Alwyn in comic mode as the young Geordie (Paul Young) is transformed from a weakly raw youth into a robust young athlete (Bill Travers).’Father and Son’ in more darkly dramatic mode, and probably the most impressive movement of the suite, with timpani to the fore underscores a scene in which an injury to an animal, in the highlands, that leads to the death of Geordie’s father. Sturdy Scottish dance rhythms inform ‘The Hammer Reel’ and finally ‘Geordie and Jean’ is lovely romantic music for the scenes between Geordie and Jean and some of the most enchanting music penned by Alwyn.

All the above music is very pleasant and often quite charming. It is played with due commitment. The trouble is that thinking back over it all I cannot remember one outstanding theme, even the enchanting ‘Geordie and Jean’ hardly presents anything novel. This for me is the difficulty I have with so much of the remainder of Alwyn’s music (after the material included in Chandos’s The Film Music of William Alwyn Vols 1 and 2) – it is to my ears, despite being excellently crafted, too derivative.

Ian Lace

3.5

Gary Dalkin adds:-

I have little to add other than I completely agree with Ian’s comment that, ‘thinking back over it all I cannot remember one outstanding theme.’ The music is expertly crafted, and does its job perfectly well in all the films for which it was composed. Unfortunately it is also no more than professionally generic, and almost completely uninspiring. I was roused briefly by ‘The Ride’ from The Rocking Horse Winner, and by parts of the suite from Geordie. Otherwise it seems Alwyn’s heart was not in it. His concert music, on the other hand, is often haunting, thrilling and unforgettable. Newcomers would be much better served by Chandos’ marvellous Alwyn – Orchestral Works (CHAN9065), including the gorgeous harp concerto Lyra Angelica and the equally wonderful Autumn Legend, Pastoral Fantasia and Tragic Interlude.Gary Dalkin

2

Return to Reviews Index