************************************************************** EDITOR'S CHOICE April 2006 **************************************************************

2-Album Review:

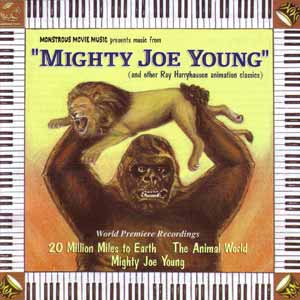

Mighty Joe Young and other Ray Harryhausen Animation Classics

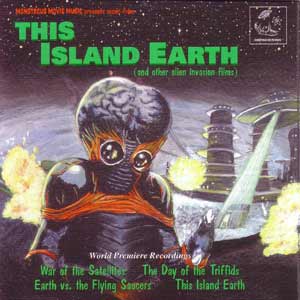

This Island Earth and other Alien Invasion Films

Music composed by Webb, Bakaleinikoff, et al

Stein, Salter, Mancini, et al

Radio Symphony Orchestra of Slovakia

Conducted by Masatoshi Mitsumoto

Album Info:

Mighty Joe Young:

Mischa Bakaleinikoff: 20 Million Miles To Earth

Paul Sawtell: The Animal World

Frederick Hollander: Heaven

This Island Earth:

The Day of the Triffids conducted by Kathleen Mayne

Walter Greene: War Of The Satellites

Herman Stein, Hans Salter, Henry Mancini: This Island Earth

Daniele Amfitheatrof: Earth Vs The Flying Saucers

Ron Goodwin: The Day Of the Triffids

Monstrous Movie Music (MMM-1953/ MMM-1954)

Running Times:

Might Joe Young: 61:48

This Island Earth: 60:12

Both albums available from MMM Recordings and other soundtrack retail outlets.

See also:

Monstrous Movie Music / More Monstrous Movie Music Creature from the Black Lagoon and other jungle creatures Mighty Joe Young (Horner) The very last line of Orson Welles’ film Citizen Kane is “throw that junk!”. And a knowing audience is witness to the callous destruction of the sledge “Rosebud”, in which the young Kane had invested so much simple childhood pleasure - and its obliteration is representative of the loss of innocence and hopeful young dreams. What may have seemed unimportant to some, was of significant value to others. And much associated with film music has, down through the years, been relegated to the same ruthless and unthinking fate that befell “Rosebud”. Over time, cost-cutting accountants, anxious for little more than “saving space” have relegated untold numbers of manuscripts and magnetic masters of film scores to bonfires and trash cans, until a great deal of our film music heritage has been eroded away, and with it, a goodly portion of our cherished childhood dreams.

Fortunately some have fought to redress this imbalance, with pressure and influence staving off the present and future discarding of film music material, and the revealing and making available of film music previously left languishing, if not deteriorating, in musty vaults. But what of that film music already “lost” to us? Happily select individuals have sought to reconstruct and re-record much of this vanished treasure trove, each more than anything spurred on a by a healthy nostalgia born of movies seen and loved in their youth. Of course many scores for the mainstream films of their day have benefited from this individual enthusiasm – the big films starring the marquee legends that remain for the most part at the peak of our movie legacy – but it should never be forgotten that the most potent of film memories, those most fixed in our minds, are of those films we frequented when children. And for many kids the bounty of those particular movies may not have merely been the saccharine or the innocently adventuresome - but the outlandish fantasy, the spooky horror film or the fanciful science fiction epic featuring bug-eyed aliens. Often scary stuff!

The record label Monstrous Movie Music (if ever there was a “giveaway” in a company name this is it!) has springboarded from the youthful enthusiasms of its founder David Schecter for vintage fantasy, horror and science fiction films to establish an ongoing schedule of reconstructing and recording lost scores for these genres, the label single-handedly re-establishing many musical gems which otherwise would or might have been denied to us forever as commercial entities. These two latest albums from the label offer a wonderfully grotesque gallery of formidable musical portraits.

Mighty Joe Young (1949) brings an unfeasibly giant ape from the wilds of Africa to the confines of an urban American jungle with predictably catastrophic results. Thankfully though the beast is pacified by the strains of Stephen Foster’s Beautiful Dreamer – but then, aren’t we all? The studio was RKO – and they assigned their top composer, the estimable and underrated Roy Webb, to the wide-ranging task of evoking everything from African and American locales to obligatory romance to monster mayhem! Webb’s opening stanzas spiced with exotic percussion conjure Africa in all its raw majesty, but there is also music of great charm here, delineating the delightfully playful relationship between the towering ape, Joe Young, and his winsome mistress, Jill, played by Terri Moore. But via numerous action titles such as Joe Runs Amok there is necessarily much strum und drang – this is not subtle scoring - but then music for rampaging giant apes seldom is! This is scoring in a venerated Hollywood symphonic tradition, and the recording is justly important in that it restores a score by one of Hollywood’s accepted masters. After fifty-seven years it was finally worth the wait to be afforded Webb’s striking music for Mighty Joe Young.

This extensive Roy Webb score would make a satisfying album in itself – but we are treated to more – lots more. Willis O’Brien was the effects supremo behind both King Kong and Mighty Joe Young, and on the latter film he had the able assistance of the young Ray Harryhausen, soon to emerge as the leading figure in stop-frame animation, and the remainder of the disc is generously filled with music from early films for which Harryhausen was creatively involved. 20 Million Miles To Earth (1957) told the touching tale of a reptilian Venusian creature brought back to earth as yet unborn in an egg, but following hatching the alien grows at an astonishing rate, soon identified as a threat and sadly subject to lethal military might. The Columbia film was produced on a modest budget, with the musical score mainly resourcefully culled together by music director Mischa Bakaleinikoff from various compositions already extant in the studio’s library – and so here we are treated to key cues by Bakeleinikoff augmented by pieces by Frederick Hollander, David Raksin, David Diamond, George Duning, Werner Heyman, Max Steiner, Daniele Amfitheotrof – quite a line up – and given that none of those composers were credited on the film, kudos to producer David Schecter for identifying all these various cues and their contributors. This all makes for fascinating listening – not least because these originally disparate pieces form a cohesive dramatic score under Bakaleinikoff’s mastery.

Rounding out the disc are two evocative selections by veteran Hollywood composer Paul Sawtell for the feature documentary film The Animal World (1956), which was ultimately dominated by some fearsome dinosaurs courtesy of Ray Harryhausen’s artistry. But just when you thought it was safe to press “eject” it seems there is one more cue to enjoy – a piece from Frederick Hollander’s score for the film Here Comes Mr Jordan, re-utilised as the opening of 20 Million Miles To Earth, but here presented in its original orchestrations rather than those created by Bakaleinikoff for the latter film.

One of the most potent and disturbing images from cinema that haunted my youth was that of the alien creature from the colourful science fiction opus This Island Earth (1955). Just to ensure that my nightmares continue into adulthood the second album this month from Monstrous Movie Music reproduces this disturbing bug-eyed, claw-fisted creature on its font cover (courtesy of a painting specially commissioned from Robert Aragon). A substantial thirty-seven minute suite from This Island Earth, with thrilling and eerie music by Herman Stein, augmented by cues composed by Hans Salter – and Henry Mancini, no less – comprise the lion’s share of this enterprising second disc, the music at once a golden template for Fifties science fiction scoring, running the gamut from the uncanny and the unnerving to the reassuringly homespun.

The album also treats us to the brief but wonderfully manic main titles to War Of The Satellites (1958) by Walter Greene and the prelude to Ray Harryhausen’s excellent and enterprising Earth Versus The Flying Saucers (1956) composed by an uncredited (on the film) Daniele Amfitheatrof. But I have to confess a particular penchant for the album’s final offering – a winning twenty-minute overview of Ron Goodwin’s music for The Day Of The Triffids (1962). Goodwin was happy to record themes and suites from his film scores but lamentably never got around to committing his Triffids music to commercial disc. This seems a pity – as this music comprises some of his very best and most apt work. The matter has now been rectified – and in fine style. And what price Goodwin’s main title music, which comes in like gangbusters – its terse, spiky rhythmic patterns laced with wailing horns heralding danger. But if I have a favourite moment from this fantastically atmospheric score, it is in the growling celli and basses which introduce us to our first Triffid, uprooted and stalking the hot house at Kew botanical gardens with venomous intent. This music made me shiver! I was taken back, as I’m sure the album’s producer intended, to that hard cinema seat in 1962 when I first watched The Day Of the Triffids, and when my then-girlfriend, confronted by that first sight of a Triffid, suddenly screamed out loud! Ah … nostalgia!!

As if the bounty of these recordings were not enough in themselves there is an additional bonus in listening to these discs for the hardened film music aficionado. Much film music recorded commercially these days pitches its ensemble into a fairly broad “classical” acoustic – and whilst this is perfectly legitimate, and can be sonically rewarding, the fact remains that much film music, and certainly a great deal of that composed for modestly budgeted films, was originally recorded in quite intimate acoustics, and ingeniously miked to capture every detail of orchestration. These new recordings from Monstrous Movie Music seek – successfully – to replicate the same kind of intimate but infinitely detailed acoustics that distinguished the original vintage recordings. Consequently this music sounds “authentic” in more ways than one. The listener is genuinely transported back to another era, albeit with the added dividend of digital recording techniques. The sterling performances of the Radio Symphony Orchestra Of Slovakia under the sure batons of Masatoshi Mitsumoto and Kathleen Mayne also bring additional veracity to the proceedings.

But I’m sorry – I have to wax even more lyrical. I know, this is becoming gushing – and I may even get cloying yet - but praise where praise is due. The CD booklets. Oh yes, the CD booklets! They are forty pages long! Everything you could ever want to know about the films, the scores (every recorded cue in detail), the composers and the recordings is reproduced here – and the tomes are lavishly illustrated too – photos of the composers, of the recording sessions, of manuscripts – even a picture of the album’s producer and his wife, the reconstructionist and conductor Kathleen Mayne, standing amid a field of Triffids! I hope they got home safely! These booklets are so stupendously annotated that I’m still reading mine – and its been three weeks already!

David Wishart

Mighty Joe Young:

5

This Island Earth:5

Return to Reviews Index