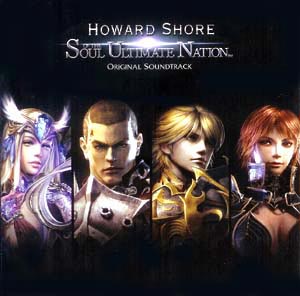

Soul of the Ultimate Nation

Music composed, produced, orchestrated, and conducted Howard Shore

Performed by National Philharmonic of Russia and Academy of Choral Arts

Featured soloists: Irina Komarova (vocals, ‘Sanctuary of Ether’) Ecaterina Popova (vocals, ‘Night of the Crescent Moon’), Lydia Kavina (theremin), Vera Volnukjina (shakuhatchi), and Ludmila Golub (organ).

Available on Sony-BMG (SB70053C)

Running Time: 64:25

Yesasia.com Catalogue No: 1004124159

See also:

The Aviator Ed Wood The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers Those dismayed at the departure of Howard Shore from last year’s King Kong remake have received an unexpected boon in early 2006 with the release of over an hour of original score for orchestra and choir written by the composer for a Korean video game called Soul of the Ultimate Nation. It’s the composer’s first video game score and a sign of the growing significance of applying cinematic techniques to new media, marking probably the first time an A-list film composer has been brought to the genre of game scoring to write an entire score in his own voice. (It’s worth pointing out that both Bruce Broughton and Graeme Revell have written complete game scores previously – Hearts of Darkness and Call of Duty 2 respectively – though neither were really A-list composers at the time.)

I can’t say whether this is the greatest game score ever written or not, as I don’t have more than a passing acquaintance with the genre. What little game music I’ve heard has always felt overly action-oriented (no surprise, since games are dominated by action sequences), with an overall lack of dramatic arc to make the albums come anywhere close to rivaling good film scores. To me what’s interesting here is whether this score is as engaging and dramatically thought out as Howard Shore’s music for film. It’s hard to get a sense of this here, as the lavish sleeve notes, including track-by-track descriptions of the scenes accompanied by each cue, are unfortunately mostly in Korean. (Except for the part we already know, the summary of Howard Shore’s career to date.) This makes it hard to discuss thematic development and structural ideas throughout the score in terms of the story it illustrates, which is unfortunate, as these are usually a strong point in Shore’s work. Only the track names give any indication of the content. With titles like ‘The Forest of Beasts’, ‘Valley of Dragons’ and ‘Graveyard of Aiort’, and graphics of stylized primitive warriors and hand-drawn maps, it seems like a fantasy role-playing game with elements of Tolkien’s Middle Earth an undeniable influence.

Which makes it no surprise that Howard Shore was headhunted by the producers of this game to provide its musical score. Initially typecast as composer for psychological thrillers and the occasional comedy, Shore’s aptitude for epic fantasy scoring was showcased in the three Lord of the Rings scores for the Tolkien adaptations. And it is that type of approach that the commissioners of this score have clearly sought to replicate. After a brief introduction of one of the main themes by shakuhatchi, the opener ‘Sancturary of Ether’ develops along the lines of the ‘Rivendell’ material from the trilogy, with arcing arpeggios, female choir (choral text by Jin Soo Park) and harp figures. When the growling male vocals enter ‘Empire Geist’, you’d swear you were in Moria again, a feeling also supported by the syncopated percussion of ‘Requiem for the Dead’. With the trilogy’s ubiquitous v-motifs bouncing from the trombones to the horns amidst an expansive mixed choral line, ‘The Triumph’ could easily be mistaken for missing cue from The Two Towers, a feeling strengthened by a near-cameo by the Fellowship theme in the trumpet towards the end of this cue.

But it sells this composition short to say it is merely another Lord of the Rings score, when it is clearly a composition that allowed Shore’s an opportunity for freer development of his musical ideas. ‘A Prelude to Revolt’ is an extended journey for orchestra and choir – presumably to accompany an expositional sequence in the game. It opens with a brass fanfare – a variant on the main theme – followed by an Aviator-like counterpointing of strings and brass, building to the entry of a woman’s choir. A virtuoso oboe solo over light 5/4 percussion over which male choir appears. And so the cue keeps going – a fluid track of significant length that continually sustains interest through inventive counterpoint and orchestration – and it’s hard to remember the last time something so ‘classical’ in its development of ideas was written for film. Another strong cue is the highlight of the action material, ‘The Valley of Dragons’. It thunders to life with syncopated brass and percussion hits before Lydia Kavina’s theremin takes the fore in a solo reading of one of the main themes. The cue as it continues is a dynamic oscillation between the full orchestral attack (again with resonant percussion, trilling horns and trombones) and the unique timbre of the theremin. It’s the best action cue Shore has ever written.

The early cues vary nicely in temperament, with ‘Tides of Hope’ delivering a warm trumpet/horn dialogue of the main theme with gentle string harmony, followed by a counterpointing of a string reading of the main theme with gentle arpeggios. ‘The Epitaph’ balances the high strings nicely against women’s choir, the melody here surprisingly reminiscent of the later Michael Nyman. Together with ‘Sanctuary of Ether’, these cues ensure the score is not merely one long action cue.

It seems on a number of levels the opportunity to score a video game opened up creative opportunities for Shore. There is an eclecticism to the writing here. The theremin has rarely strayed outside the genre of science fiction, and to hear the melodic use of it here (the opening of ‘Night of the Crescent Moon’, the extended solo of ‘Hymns of Battlefields’, ‘A Pernicious Plot’) is fresh indeed, this reviewer wishing there was more of it. It’s very different from the referential use Shore made of it in Ed Wood, in this score sounding more like what Elmer Bernstein did with the instruments aural cousin, the ondes martinet in Heavy Metal and The Black Cauldron. Together with the shakuhatchi (‘Sanctuary of Ether’, latter half of ‘Poem for Nemesis’ with male choir) and organ (‘Immortal Emperor’), the range of instrumentation open to Shore here would not have suited the pre-modern palette the composer restricted himself to in the Tolkien adaptations.

It’s endemic of a series of subtle differences to Shore’s writing in this score. While the choral-orchestral blend may suggest the trilogy superficially, overall the composition is closer to the two-voice writing of The Aviator. (Take the string and theremin counterpoint in ‘Hymns of Battlefields’.) There are other modern flourishes – the oboe in ‘Prelude to Revolt’ feels almost baroque in its self-conscious formalism. Overall the cues feel less constrained to the economical demands of film music storytelling, with tracks of extended length like ‘Requiem for the Dead’ and ‘Menace of the Army Wings’ where ideas are able to develop to their full extent (and in some cases, past it).

Similarly there’s a freedom to the orchestration – an array of more expressive brass and percussion touches than Shore’s music for the trilogy. In ‘The Triumph’ the unusual blend of snare drums rhythms and divisi string writing towards the end of the cue, as well as the trilling horn dissonances, would never have been heard in the trilogy soundscape. Note particularly the percussion of the concluding ‘Menace of the Army Wings’, and the many aggressive dissonances in the action tracks. There’s even a cue based on material never used in the score for The Two Towers, the shimmering two-voice brass melody and arpeggios in ‘Forest of the Beasts’ that appeared in a slightly different form for an excised cue in The Two Towers that accompanied Gandalf’s resurrection.

Not that you’d know it from all this, but it’s not an album without flaws. Firstly, the album is poorly structured, the best of the cues generally out there in the first half, with little of the second half that quite matches up to that early material. Why does the score end where it ends, at the climax of an action track? Some cutting of minor cues and rearrangement of the track order might have fixed this, though even then there might be the problem of this album’s persistently stern tone. There’s little relief from the tension.

Secondly – and this is inherent to the genre of game scoring – some of the cues have that feel of ‘waiting for the game player’ to get through the round, particularly in ‘Requiem for the Dead’ and ‘Menace of the Army Wings’. It is action music, but it’s trying to sustain a mood of action that can be conceivably looped for as long as the player takes to complete that scene, and to someone used to the relatively concise development of film action cues, this more protracted development gives the action a strange existential feel.

Thirdly, the mixing approach that Shore and Kurlander have gone for on multiple successive scores suppresses the detail in the writing for the sake of the power, so that even the solo parts escape with some difficulty from the bassy mix. I remember hearing all manner of detail in the Lord of the Rings Symphony mixes that were mixed out of the albums, and I suspect there’s some fine orchestrations disguised here too. Why not remix for album so that the music can be heard as a composition, independent of its dramatic role in the game?

However I shouldn’t make too much of these problems. I haven’t heard that many game scores, but this is certainly the best of what I have heard. For fans Howard Shore acquired among the Tolkien set, it’s a nice return to action on the scale of Lord of the Rings after the more psychological approaches to The Aviator and History of Violence. I can’t say I like it as much as the score album of the Scorsese Howard Hughes biopic for the reasons discussed above. It does whet the appetite though for his score for the Scorsese remake of Infernal Affairs, and for whatever he managed to complete on King Kong before he left the project.

Michael McLennan

Rating:

4

Return to Reviews Index