************************************************************** EDITOR'S RECOMMENDATION Fall [1] 2005 **************************************************************

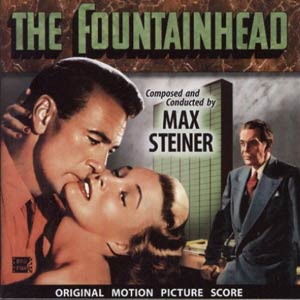

The Fountainhead

Music composed by Max Steiner

Available on BYU (Brigham Young University) Film Music Archives (FMA-MS114)

Running Time: 57:30

‘The most bizarre movie in both Vidor’s and Cooper’s filmographies, this adaptation mutes Ms rand’s neo-Nietzshian philosophy of “objectivism” but lays on the expressionist symbolism with a free enterprise trowel’ -- Time Out 1980.

The Fountainhead (Warner Bros. 1949) was about an idealistic young architect who refuses to compromise his designs and clashes with less talented competitors and the more conventional tastes and interests of big business and architectural commentators. Its uncompromising message was that the pioneering artistic spirit of the true, talented and individual artist must prevail over mediocrity often championed by the majority.

Gary Cooper starred as architect Howard Roark, Patricia Neal as the psychologically disturbed, architectural correspondent and Roark’s love interest, Dominique, with Raymond Massey as Gail Wynand, the newspaper magnate who supports Roark until adverse public opinion threatens to ruin his business. Robert Douglas in a major supporting role plays the film’s villain, the influential but oily architectural critic, Ellsworth Toohey.

The story seems to have struck a sympathetic chord with Steiner for he wrote one of his most inspired scores for the film – one that surely deserved at least an Academy Award nomination? True to the aspiring spirit of the story Steiner’s main theme for Roark is as strong and soaring as the buildings he designed – this is one of Steiner’s most memorable, most mighty themes. Its obverse is Dominique’s theme described most aptly by Christopher Palmer, in his excellent book, The Composer in Hollywood, as wending ‘downwards in curves of typically feminine shapeliness’. Almost all of the film’s score is made up of variations of this material. A particularly ‘slithering malevolent’, dissonant ‘modern-sounding’ theme is reserved for the snide Ellsworth Toohey.

From this wonderful score I would just mention two major cues.

‘The Quarry’ is a master stroke, Steiner’s music revealing layers of meaning. The scene is famous. Dominique is visiting her father’s quarry. She looks down and is fascinated the muscular Roark operating a drill. Steiner catches the atmosphere of sexual tension magically. Quoting Palmer again, ‘Steiner takes [Dominique’s theme] but projects the melody on high violins, flute and vibraphone, with little harmonic or textural support other than the naturally reverberative properties of vibraphone, soft bass-drumroll and tam-tam. Their overtones, mingling and lingering in the atmosphere, complement director King Vidor’s insistence upon the heat-haze and white chalk dust which permeate the scene. The effect of this extreme starkness thrown into relief against a quasi-impressionistic glow is to communicate the full force of Roark’s frustrated desire.’ Furthermore in the brief cue that follows ‘Dominique fantasises about Roark’ we hear the drill again suggested very graphically by a xylophone.

The other cue I would single out is ‘Dominique’s Theme for Piano’ the piano solo perfectly catching Dominique’s changeful, conflicting emotions about Roark. The preceding cue Piano for Secondhanders’ is an interesting contrast, another piano solo suggesting the vacuity of a cocktail party before the arrival of Roark. [I must confess though to a certain partiality for this so-called dissonant music, a case where Steiner was too tasteful for the plot line?].

The 32-page booklet carries many stills from the film, together with a track-by-track analysis, an introductory article from James D’Arc, curator of the Brigham Young University Film Music Archives and a fascinating essay, ‘The Fountainhead: A Great Flawed Film’, that covers the novel and its author, Ayn Rand, that inspired the film and the development of its production. We learn that the producers wanted Frank Lloyd Wright to design the sets but his consultancy fee of 10% of the film’s total production (not just the set and models budget of $400, 000) was unacceptable. There were quarrels as shooting progressed and Rand threatened to take her name off the picture over disagreements about Gary Cooper’s famous court room speech. Despite Jack Warner’s assurances to her that her speech script was not to be tampered with she was incensed when on the film’s release she discovered one vital line of that speech had been deleted: the opening “I wished to come here and say that I am a man who does not exits for others.”

One of Max Steiner’s most inspired scores as soaring and magnificent as one of

Roark’s towering buildings.

Ian Lace

5

Return to Reviews Index