DVD Review

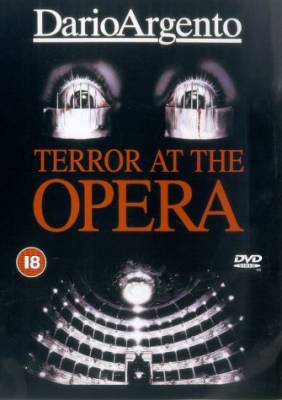

Opera (Terror at the Opera)

Director Dario Argento

Studio: Arrow Film Distributors Ltd.

Run Time: 107 minutes

Region 2 encoding

Subtitled, PAL

Amazon UK

Dario Argento is perhaps the most stylish horror film director of the last 30 years, although his art has often been fraught with censorship difficulties both in the United States, where Phenomena (re-christened Creepers) and Tenebrae (renamed Insane) were heavily cut. In the UK the latter was successfully prosecuted as a video nasty and has only this year become available in an uncensored version (from Anchor Bay DVD). Opera (aka Terror at the Opera, 1987), for so long one of his most under-rated films, also suffered at the hands of the UK censor, but this new DVD version handsomely restores it to its director’s cut.

Masterfully crafted, beautifully shot and with a score by Verdi (as well as his usual composer Claudio Simonetti) it can now be seen as his masterpiece (at least until he made Sleepless in 2000). Centring round an avant-garde production of Verdi’s Macbeth (the subject for the film came from Argento’s aborted attempt to stage a production of Rigoletto in Macerata in 1985) the film’s heroine (played by Christina Marsillach) finds herself thrust into the role of Lady Macbeth after a mysterious car accident causes the indisposition of the opera’s original leading lady. There follows a series of murders, savage in their brutality, before a surreal climax where the killer’s identity is revealed. If the plot is thin (as is so often the case with Argento films) it is the sheer virtuosity of this director’s style which makes the film both so watchable and so unique, even within the Italian giallo genre.

Argento’s films could justifiably be criticised as displaying astonishing set pieces within the larger framework of an unworkable plot. Tenebrae is so often an exercise in visual brilliance (the lasting image of a camera tracing the advancing footsteps of a murderer across the outside and roof of a tenement block is one of the most extraordinary in cinema) and Opera is equally inventive. The climax of the film itself, when the ravens are let loose to hunt down the killer within the audience, is filmed entirely from the viewpoint of the ravens – at once circling high within the vaults of the opera house, then suddenly swooping down into the audience itself, before soaring upwards again. When they locate the killer (for it is the ravens who have witnessed one of his murders) they attack him with ferocious power, pecking out one of his eyeballs (a neat solution given the killer’s earlier brutality towards the ravens). The superb documentary on the DVD explains how this scene was shot – two cameras, 180 degrees apart, on a rotating platform constantly circling the auditorium. Yet, even this marvel is not the highlight of the film. That honour goes to the death of Argento’s then partner, Daria Nocolodi, who peering through a spy-hole is shot through the eye at close range, the bullet exiting the back of her head on a trajectory to hit the telephone. What makes the scene exceptional is that it is filmed entirely in slow motion.

Opera is typically voyeuristic, as all Argento’s films are, but the voyeurism here is slightly crueller. As usual, it is really only the gloved hand of the killer (rumoured to be Argento himself in most of his films) that we see but where this film differs is in the way Argento makes his victim (for that is precisely what Marsillach is) a witness to many of the murders. Tied up, with needles taped to her eyelids so she must ‘see’ the action to prevent blinding herself, the discomfort for the viewer is palpable. At times we see exactly what she does, through a net of needles. Perhaps even more unsettling is the dispassionate way in which so many of these people are characterised. Marsillach’s performance is understated in the sense that she seems to generate little response to the murders happening around her. She sees horror, but her reactions to it are largely motivated by indifference. Ian Charleson’s director is in part an odious character – temperamental, brusque and unemotional. When he himself is murdered (in a weak ending to the film) Marsillach seems more interested in smelling flowers.

Argento has suggested that his characters’ indifferences, their oblique attitude towards sex and their lack of interaction are his response to the AIDS crisis, then at its peak. The complete undermining of personal relationships – and where sex itself is an act of death – is part of the parcel of Argento’s view that Opera is a film that could only have been made when it was: its giallo horrors and politicisation are epochal of 1980s selfishness and disorder (this was also a period of soaring serial killer activity).

It is an irony that the sets and cinematography are so in contrast to this viewpoint. Filmed at the Teatro Regio Opera House in Parma, it drips with opulence, and in many ways this, and Verdi’s music, are counterbalances to Argento’s cynicism of the events being played out both on screen and in the opera itself. Ronnie Taylor’s camera work (so breathtaking in Attenborough’s Gandhi) has that film’s epic breadth, albeit within more confined spaces, but its concentration on colour and beauty is definitive. The DVD transfer – in the correctly framed 2.35:1 aspect ratio it should be added – makes some of the scenes look a little darker than they are in the trailers but visually this is a stunning remastering. Sound-wise, the 2.0 stereo or 5.1 digital sound is exemplary, giving real presence to Verdi’s score, as well as Goblin’s heavy metal additions. What, however, makes the DVD of this film so attractive is that it, for the very first time outside the cinema, allows us to view Argento’s masterpiece as he would wish it to be seen.

Marc Bridle

Film

41/2

DVD5

Return to Index