Film Review

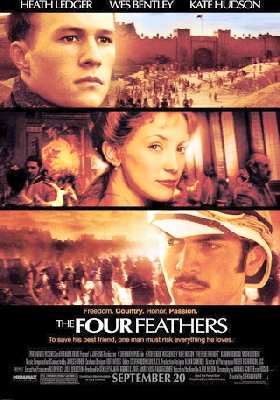

The Four Feathers (2002)

Directed by Shekhar Kapur

Music composed by James Horner

Principal cast: Heath Ledger

Wes Bentley

Kate Hudson

Djimon Hounsou

Michael Sheen

Miramax Films

Running time 130 minutes

Certificate 15

UK release date 25 July, 2003

This is the seventh film version of A.E.W Mason’s Victorian adventure story – the first having been made in 1915. Kapur’s touch for the visual – so conspicuously influenced by David Lean in this film – makes this 2002 version the most cinematographically successful to date, although memories of Korda’s magnificent 1939 film are never really erased - a stirring, if flawed, example of the book-to-celluloid transition.

Although Kapur – through his screenwriters Michael Schiffer and Hossein Amini – has returned to the novel in greater detail than before there are disadvantages to this approach. At least with Korda the beginning of the film had a truly romantic passion to it, in part derived from the emotions of the times in which it was made; in contrast, Kapur seems unable to generate any equitable sense of romantic tension between his three young leads. Ledger’s Harry is almost an affront to the stereotypical male lead whereas Kate Hudson’s fiancée is both sexually and emotionally remote. This makes the first 40 minutes of the film a very stolid affair – although, in part, one must question whether Kapur deliberately meant it to be this way. His conception of their affair is certainly more innately Victorian than Korda’s ever was.

Where the film takes off – and where its values change – is in the Sudan scenes. If Korda’s film had been about the morality of redemption, it is less certain that this is really Kapur’s motive. Korda had his Harry deliberately journeying to regain his honour; Kapur seems to be less concerned about the concept of honour and more about that of a wronged young man determined to adventure into the unknown in an attempt to discover his own soul. Kapur’s Harry is closer to the French poet Rimbaud than in any other characterisation of the role and that leaves unanswered questions. Similarly, by choosing Kapur to direct the studio could hardly have anticipated a film which gave a pro-colonial view of British global power. The view that the British Empire was on a mission to save the world from the scourge of atheism – and promote its own Christian morality to an unwilling people - is discarded by Kapur in favour of a viewpoint that imagines the British as violent, intransigent occupiers, and its officer soldiers as racist and arrogant.

Kapur’s real energy (and real motives) are reserved for the vast battle scenes and panoramic images of the Sudanese desert. They are indeed spectacular – confirming the impression that this is a film that is out of kilter with the times in which it was made. Cavalry charges, overhead shots of the British regiment surrounded by the Sudanese rebels – reminiscent of the scenes in Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo – and the scale of the defeat are all magnificently handled. Harry’s subsequent decision to return to the prison to save another of the fops who delivered him the white feather allows Kapur to produce a surreal world reminiscent of the Black Hole of Calcutta (a nice irony in that it reverts the conventions of what we know about it).

Similarly, Kapur introduces the figure of Abou Fatmer (played by Hounsou) as a kind of Guardian Angel – but it reflects the view that Harry is unable to determine his own resolution without the help of someone supposedly inferior to himself (although, by this stage, Kapur has ensured that Harry’s search for his soul has also allowed him to radically reverse the views of 20 years of indoctrinated British superiority and arrogance).

This The Four Feathers is less memorable because of with its confused politicisation and overbearing morality. Strikingly visual though it maybe, however, Kapur’s imagery – by the gifted Robert Richardson – seems partly to overwhelm the director’s own viewpoint. If it is derivative of Lean it not necessarily inferior to Lean – and a lack of special effects only makes it more stunning to look at. Lean had his desert, and so does Kapur. Lean had his mirage of the young Omar Sharif appearing as if on water; Kapur has his of a final fight to the death between Harry and his captor where the sand dunes come to resemble vast tides of water. As Harry’s face is pushed into the sand it looks as if he is being drowned. By any stretch it makes a visual impact and makes the film rewarding on at least this level.

Less distinguished is James Horner’s score – often too soporific – and often without any real sense of the unfolding panorama on screen. A use of ethnic vocals perhaps undermines Kapur’s overweening sense of morality, if it doesn’t actually drive the viewer slightly mad first. The performances are little more than satisfactory – Ledger is affable, but not much else, and both Bentley and Hudson (with strangulated English vowels) seem out of their depth.

Watch this film only for its stunning imagery. As an adventure story, with the values of an Edwardian writer left intact, stick with Korda’s so far unrivalled 1939 version.

Marc Bridle

21/2

Return to Index