![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| April 2001 Film Music CD Reviews |

Film Music Editor: Ian Lace |

index page/ monthly listings /April01/

************************************************************** EDITOR’s RECOMMENDATION April 2001 **************************************************************

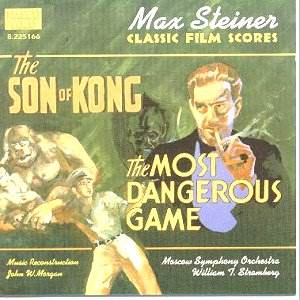

Max STEINER The Son of Kong; The Most Dangerous Game

Moscow Symphony Orchestra conducted by William T. Stromberg

MARCO POLO 8.225166 [77:19]

Crotchet AmazonUK AmazonUS

This disc follows the same team's essential 1996 recording of Max Steiner's complete King Kong (1933) score (Marco Polo 8.223763). It does something which is obvious retrospectively, which is to re-record two further complete scores by Steiner, both directly related to King Kong, and present them on a single disc. Remarkably, the two scores together have a total playing time of 77 minutes, 19 seconds, and thus combine to make one exceptionally well filled CD.

The album comes with a 36 page booklet which is absolutely packed with notes by various hands, plus excellent stills, behind-the-scenes photographs and manuscript reproductions. In-fact, the notes tell us just about everything most people could want to know both about the films and the music, as well as providing some nicely human anecdotes about Steiner. They do though become a little repetitive, such that further editing wouldn't have gone amiss. We do learn that, during The Depression Merian C. Cooper was entrusted at RKO with discarding many of the unsuitable projects which had accumulated, whilst simultaneously deciding what to 'greenlight'. He already had the idea for King Kong, but knew it would require a large budget, and was supposed to be cutting projects, not initiating fresh ones. In The Most Dangerous Game he saw the potential for both testing the viability of a jungle adventure, and even having sets built which could be reused should King Kong go before the cameras. Thus he put The Most Dangerous Game into production, a thriller adapted from a 1924 short story by Richard Connell, in which a mad aristocrat hunts humans for sport.

Max Steiner was begged to take over and write a replacement score, despite an already massive workload which would eventually result in him leaving RKO, when the original score by W. Franke Harling proved too light. The film runs a tight 63 minutes, almost exactly half of which is scored, the re-recording, divided into 15 cues, here playing for a little under 32 minutes. This is music from the dawn of the synchronised score era, and while Steiner had written other synchronised scores prior to this some argue The Most Dangerous Game, rather than King Kong, is the first great film score of the 'sound' era.

One of the problems in considering film music from the early 30's is that the comparatively primitive recording techniques of the time didn't allow, especially once the music had been mixed with dialogue and sound effects, the rich detail of a score to be heard. A second problem that faced Steiner particularly on both The Most Dangerous Game and The Son of Kong (1933) is that the small orchestras he was forced to use weren't big enough to deliver the full impact of his music. The orchestra for The Son of Kong had just 28 musicians! For this recording the score has been reconstructed from Steiner's original manuscripts by John W. Morgan, and reorchestrated - the original orchestrations no longer exist in any case - for more conventionally sized symphonic forces. Thus the music here is a realisation of how Steiner's scores could have sounded in an ideal world with modern recording techniques and an appropriate compliment of players. Some extreme purists may object, but the original recordings sounded the way they did out of necessity, not because anyone wanted them to sound that way, and this current re-recording has been made with the full blessing and co-operation of the late composer's wife, ex-RKO studio orchestra harpist Louise Steiner Elian. Such 'classical' approaches have even been used as putting two horn players 'off stage' to create the effect of distant hunting horns.

All this considered, even those who are very familiar with the films will find there is much more to these scores than they have ever heard before. The Most Dangerous Game today may risk sounding clichéd, not through any lack of invention on the composer's part, but simply because it was the first of its kind, was so successful, and so widely imitated for so long afterwards. Based around a waltz of Steiner's own invention - he preferred to write his own 'source music' - and developed into a rousing suspense motif, this is literally the foundation of modern film scoring. Indeed, Steiner used suspense building techniques such as slowing rising chords which gather to a crescendo which are still in use in thrillers, SF movies and horror pictures today. As the booklet notes point out, there is a certain amount of 'Mickey Mousing' of the action. It is also noted that Steiner was and remains far from the only composer to use the method, though he has been most often castigated for it. What it does mean is that the music often falls into stop-start patterns closely linked to screen action the CD listener obviously can not see. This is highly functional, very well crafted action suspense music, with an undoubtedly highly significant place in film, and film music history. Much of it though is probably not as enjoyable to a modern listener as more recent scores by Rózsa, Herrmann, Goldsmith and Williams.

What is not in doubt is the appeal and sheer brilliance of the writing for the final chase sequence and fight. This is breathlessly exciting music and a real tour de force of action scoring. The relentless, brutal pulse leaves the listener almost gasping for breath, demonstrating that right from the beginning of the synchronised sound era powerful music was essential to the generation of screen excitement and suspense. For these cues alone, The Most Dangerous Game was a landmark in cinema.

If The Most Dangerous Game remains a screen classic, The Son of Kong is anything but. A rushed and half-baked sequel made without any real story to tell, and without a budget to tell it. The Son of Kong was rushed to cash-in of the success of its parent. But where King Kong had cost $650 000, The Song of Kong cost just $250 000 and was on screens within 6 months of King Kong's opening. It remains one of the most pointless follow-ups ever made. Carl Denham, the adventurer hero from the first film, flees from those wanting to make him pay for Kong's damage to New York, teams up with another attractive young woman, this time played by Helen Mack, and eventually returns to Skull Island. Here they find Kong's 12 foot high albino, and friendly, son. Horror and pathos are replaced with comedy and sentiment, until a ridiculous deus ex machina brings proceedings to a close as an earthquake suddenly destroys Skull Island, dinosaurs, natives, Son of Kong and all except our young romantic couple. This is mediocre stuff, and therein lies the reason why many fans of Steiner's score for King Kong will be disappointed by his music for The Son of Kong.

Where King Kong gave Steiner the opportunity to write an epic orchestral score full of fury, menace, excitement and outright terror, which today still influences blockbuster scores from James Horner's Aliens (1986) to John Williams' The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), The Son of Kong afforded few such moments. This was second rate melodrama littered with light, often slapstick comedy. Consequently, while the composer reused some of his previous material for continuity, he based much of the new score around a fresh tune of his devising, 'Runaway Blues'. Much of what follows in the 45 minute score has a far lighter character than the music for King Kong, being closer to the Broadway style of the time than the post-Wagnerian approach of classic Golden Age Hollywood film scoring. It is, it barely needs saying, very well crafted, but for those hoping for more music similar t that found on the marvellous King Kong album, this may well prove a major disappointment. Once the readjustment has been made, there is much to appreciate here, though regardless of the booklet claims for the greatness of the score, it is hard to see this as more than expertly-crafted underscore for what is a very second-rate sequel. Not everything old is classic.

With first-rate recorded sound, painstaking and loving attention to detail, and with simply wonderful packaging, this is a release of enormous with strong appeal to anyone with an interest in the dawn of synchronised film scoring, the music of Max Steiner, or the early days of thrillers, fantasy and horror movies. The music however, simply isn't that great. I can well imagine the later cues from The Most Dangerous Game being re-recorded again to make an excellent suite on a compilation album, but otherwise, while this music is of importance I suspect that few with sufficiently enjoy it to want to replay the complete album often. Or perhaps it is simply a generational matter; the introduction to the booklet is by the great fantasy film-maker Ray Harryhausen, who declares how he has long wanted new recordings of these scores and never dreamed to have them. And who am I to disagree with Ray Harryhausen?

Gary S. Dalkin

- sound, presentation and historical importance

- The Most Dangerous Game

- The Son of Kong

Simon Jenner is more enthusiastic:-

It was hard luck on Max Steiner having the same dates as Stravinsky (1888-1971) and not being recognised as the innovator he was. Hard luck too that he was trounced by Korngold, nine years his junior and who predeceased him by 14 years. One can only recall Korngold's riposte to Max Steiner's quip about Korngold getting worse and Steiner better. 'That's easy, Steiner ... you have been stealing from me and I have been stealing from you.'

To disprove that here are two scores dating from 1932 and 1931 respectively. That is (though the booklet, understandably, hardly mentions Korngold at all) a couple of years before Korngold wrote his score for A Midsummer Night's Dream and six years before Robin Hood et al began the Viennese invasion from 1937.

Steiner, whose brilliant orchestrator Bernhard Kaun had to follow the breakneck schedules, was usually rushed off his spools. He annoyed RKO boss Kahane by saying his hours were now 9am-6pm, not 9am-9am, and that the May Company were not hiring him to sleep in their window to prove that even RKO composers could sleep in their beds. Kahane thought he should accept their offer of a career, and all Hollywood got the joke except Kahane. Stokowski, Klemperer and Reiner were taking Steiner seriously even before the advent of Korngold.

This was in part due not to King Kong, but to the movie that preceded it, The Most Dangerous Game, a real classic of pursuit and generally recognised as the first great film score. With its tritone theme on horns signalling the chase, the film washes ruggedly handsome Joel McCrea onto an island. He meets the sinister welcoming Count, Leslie Banks and guests, amongst whom hapless Fay Wray looms. What else would he do but attract her, so dashingly dishevelled, but still washed? She pairs with McCrea, in a kind of offer they can't refuse, to be hunted down. Guess you the rest, as Marlowe says in his version of Ovid's Amores. That bit comes only at the end, whilst the tritone (turning into a two-note motto at times) hunts down the fugitives through swamps, canyons, waterfall-fights à la Sherlock/Moriarty; and finales. The driving score never lets up and is in fact a true symphonic poem, a tremendous post-Straussian feat. Now we know where North by Northwest comes from.

And we know where the next score derived from, in the title. Son of Kong was a hurried and ridiculously under-financed attempt to cap King Kong, itself containing Steiner's most famous score. Like most scores, Kong was overlooked by many, but not by those who mattered. Hence, Steiner was forced, like the rest of the Kong team, to attempt a six-month schedule. He had two weeks to write 45 minutes' worth of music. Amazingly, as Bill Whitaker - one of the two writers of this excellent, sumptuous booklet - says, it's masterly. It's more coherent and satisfying to listen through as a complete score than Kong, for all of that score's verve and ground-breaking power. At its heart there is not a tritone but a song sung by the hapless heroine Helen Mack: 'I've got the runaway blues'. This runs on a catchy original tune which recurs throughout this adventure in which Robert Armstrong again shipwrecks himself on Kong island. This time though, son of Kong turns out a cutie, trapped in quicksands. They rescue him and bandage his massive paw - comically and touchingly highlighted in Steiner's pin-point score.

Ultimately the ingredients of a great fantasy ran to quicksanded exhaustions of their own as the scriptwriter ran out of ideas and floundered. Bandages were strictly for studio bosses, and many felt pretty well walking wounded by the end of this manic, almost shot-gun project. Son of Kong sacrifices himself to save Armstrong, Mack et al. Twit. A motif recalling him and his noble sacrifice floats up poignantly at the end. Of course the nice Kong would be back as Godzilla. Most of the score is new, despite some quotes from the earlier work, and 'the runaway blues' is the new theme at the core. Many pointillist references are made throughout, whether to Chinese ports or quicksands, Steiner manages to convey and differentiate this with great effect. Try tracking through the works to 'I Dakang', the un-PC 'Chinese Chatter', 'Quicksand - little Kong', 'Finger Fixings' or 'The Old Temple'. There's even a sly reference to 'Johnny Get Your Gun' as part of the plot.

Marco Polo, the Moscow Symphony Orchestra and William T Stromberg have produced one of their finest efforts. The MSO must feel thoroughly at home in Hollywood now. John T Morgan reconstructed the score partly from the film tracks. Ron Fortier and Bill Whitaker have supplied detailed and witty histories, littered with photographs (some very funny, try Steiner in the bath with a colleague), detailed synopses and musicological notes. There's even an Arranger's Notes and a holograph page of the score. Thirty-five pages doesn't seem too many, and this production fully justifies its Marco Polo cost. Even non-film listeners should hear it as an example of what Steiner and others were trying before Korngold arrived. From this music they were fashioning the film sound world that so influenced contemporary and later composers in every field. Two sparky masterworks of the film world, newly revealed, like minerals from the dust of sound tracks. Like the lead characters, don't hesitate.

Simon Jenner

So, too is Jeffrey Wheeler

The latest classic film score restoration from the Marco Polo label nearly spills out from its disc. Most Marco Polo releases seem a touch better than the one before; thankfully, the presentation of "The Son of Kong" and "The Most Dangerous Game" continues the trend to push soundtrack re-recording standards higher. There are nearly 80 minutes of full-bodied, ageless Max Steiner music -- a platform for what may be two of the best scores from the early 1930s.

"The Son of Kong" is a 'serio-comic fantasy' score that utilizes motifs from "King Kong", expertly redevelops them, then introduces attractive new material, including a blues theme that gets a variation in nearly every track yet never quite overstays its welcome. It is a classy adventure score, full of Thirties stylishness and wittier primal contrasts to those of the original. I never noticed the composer's woodwind approach so clearly before this. Kong, Jr. does well by his good, misunderstood old dad.

"The Most Dangerous Game" is an earlier and creepier underscore for another jungle island, one much more seriously inhabited by a man-hunting man instead of a vertically inconvenienced ape. Its sinister brass accents and deceptive moments of brightness are hardly new to anyone versed in the period's thriller underscores, but Steiner's ranks among the most significant. Some speak of his composition for the nerve-racking final chase as being the most exciting film music written at that time. It is unambiguously intense. A charming Russian waltz and a lighter secondary theme (the score's weakest element) flesh out the musical characterizations.

John W. Morgan reconstructed the music from Steiner's original handwritten sketches. The RKO orchestra was too diminutive for the composer's wishes, and while terrific performances from the players boosted the sound there were planned textures and orchestral colors economized or lost completely. Morgan carefully restored the original indications for full orchestra. The Moscow Symphony Orchestra provides stellar performances for this album, practically faultless to these ears, and its conductor, William T. Stromberg, continues to establish himself as the foremost interpreter of film scores as he ushers the conducting panache of the Golden Age studio orchestras into another age and place of great music recording. The sound of the disc is equally spectacular, with every section so intimately captured that it is as though one can single out the individual instruments. Production credits are typically superior, featuring extensive liner notes, words from special effects legend, Ray Harryhausen, film stills, and behind-the-scenes glimpses of Max Steiner and company. This is an inviolable release in every aspect. Every glorious aspect.

Jeffrey Wheeler

Return to Index

You can purchase CDs, tickets and musician's accessories and Save around 22% with these retailers: |

||||||||

|