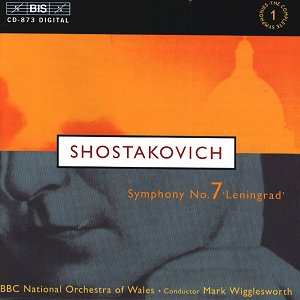

I hope that any readers who recall this conductor’s

appearance a few years ago in a truly dreadful documentary on UK television

about this symphony will not be deterred from adding this very fine

disc to their collections. Naively, the documentary rehashed the tired

old cliché (now discredited) that the work was written mainly

as a reaction to Hitler’s invasion of the USSR, and Mark Wigglesworth,

the central figure in the programme, gave viewers little confidence

in his potential as a recording artist by declaring, with gross generalisation,

that music-making in a ‘live’ concert is always preferable

to that achieved in a studio without an audience present.

Ironically, Wigglesworth’s account of the Leningrad

conveys a greater sense of concentration than I have experienced in

any ‘live’ performance; the conductor’s attention to

detail results in the listener’s attention being commanded throughout:

there are moments where the performance diverges significantly from

others, yet when one consults the score, often one finds that the effect

is achieved not by altering the composer’s markings but rather

by taking them more literally than one hears normally, such as the crescendo

in the first movement at 5’40", more threatening here than in other

recordings, or the gruff explosion on horns at 11’23", toned down

elsewhere but played sf on this recording, as marked. Much of

the individuality of this reading derives from the care taken over string

articulation, such as the crescendi through the duration of the note

which Wigglesworth asks for at 15’02" in the finale: Shostakovich

has written tenuto at this point, and the crescendi are a valid

(although unusual) way to realise this instruction. The strings employ

a variety of different degrees of legato or detached bowing and sometimes

the articulation is legato when normally one hears the notes separated,

or vice versa; although many of the changes in phrasing are not marked

in the score, it is known that often Shostakovich allowed performers

considerable licence in the freedom with which they approached his music,

and since Wigglesworth took the trouble to consult Ilya Musin (1904-1999),

the Russian conductor who gave the second-ever performance of this symphony,

it may be that some of these variants are as authentic as they are striking:

note the piercing use of the violins’ open string at 6’14"

in the second movement and from 8’07" in the third movement, an

effect which Shostakovich himself did not stipulate specifically here,

but which he implied elsewhere (for instance, in the first movement

of the Fourth Quartet and the third movement of the Eighth Quartet).

One mannerism which I find irritating in Wigglesworth’s

recording is his occasional use of string portamenti, perhaps introduced

here in order to emphasise Shostakovich’s debt to Mahler: the slide

down of a semitone by the violins in the third movement at 2’33"

(repeated at 11’31") serves no expresive purpose, whilst the glissando

at 11’17" (where all the violins drift up at different speeds,

out of synchronisation) is simply grotesque. For me, this recording

is disfigured by such slides, not least in the finale at 14’30"

& 14’41", which remind me of the tasteless, outdated style

of orchestral playing which one hears on recordings from the 1920s.

It is also a pity that there are too many passing dissonances caused

by disagreements within the violins over notes (the worst being at 1’23"

in the third movement - and why was the confusion in the woodwind at

18’30" not corrected?) and that standard misprints in the published

orchestral parts are retained (such as the middle voice of the divided

second violins at 27’32" in the first movement, also wrong on Leonard

Bernstein’s ‘live’ 1988 DG recording with the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra.

The DG performance, too long at 85 minutes to fit onto

a single CD, is coupled with the First Symphony on a two-disc set, (427632-2);

do not mistake this version for Bernstein’s much-inferior 1962

recording with the New York Philharmonic, which cuts forty bars from

the first movement. The 1988 performance is immensely compelling; no

other version has presented the climax of the first movement with such

intimidating force, and DG’s dynamic range here is amazing, from

an insane fortissimo down to a barely-audible whisper from the unaccompanied

clarinet at bar 561 (compare the sound levels at 20’54" & 23’41"

on the DG recording!) Characteristics of the sound quality can make

a substantial contribution to the perceived effect of any performance,

and as the first movement crescendo progresses, the difference between

the engineering of the two versions becomes apparent: the dynamic range

of the BIS recording proves to be extreme too, but although the sound

is good and naturally balanced, it is more recessed, compromising clarity

in the heavily-scored passages, whereas the engineering from DG has

greater focus, closer miking, and conveys a colossal sense of weight.

It would be an unfair exaggeration to claim that Bernstein

makes his impact primarily through bold gestures, but nevertheless when

one compares his reading with Wigglesworth, one finds that it is the

latter who characterises every detail of the score with more subtlety.

Compare their accounts of the long G major second subject in the first

movement: Bernstein relies on the creation of a mere generalised mood,

but when Wigglesworth arrives at the Das Lied von der Erde chord

(5’50"), it has the same air of unease as when Shostakovich reuses

it at the end of the third movement of his Tenth Symphony, thanks to

the care this conductor has taken over gradations of balance during

the preceding four minutes of quiet music. In the central repetitive

section, Bernstein portrays the belligerent, thuggish arrogance represented

by this passage, but Wigglesworth’s approach is contrasting: he

begins at a genuine ppp and his build-up is more refined. The

muted brass are so distant at 10’36" that I suspect they were playing

offstage; this eerie effect is reminiscent of the moment in Act 3 of

Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk where the brass instruments,

playing quietly with (as in the Leningrad) repeated notes at

the end of each phrase, depict the arrival of the police.

It would take too much space to discuss every interesting

facet of the BIS version, but I hope that I have said enough to persuade

Shostakovich enthusiasts to hear this remarkable disc for themselves.

Wigglesworth provides his own sensitive booklet notes, their ‘revisionist’

post-Soviet tone complemented by the character of his performance, but

I was puzzled as to why these notes imply that there is genuine optimism

at the conclusion of the work, when my impression was that his performance

of the finale sought consciously to emphasise the parallel with the

last movement of the Fifth Symphony: once the initial fast tempo of

the Seventh Symphony’s finale ceases, a grim procession takes over,

handled superbly here, sleepwalking impersonally to the dazed ‘forced

optimism’ of the conclusion (significantly avoiding any rit, even

before the last chord, so as to avoid suggesting grandeur). Apart from

the pitchless bass drum, the lowest note in this final chord is the

octave below middle C: isn’t Shostakovich hinting symbolically

at ‘forced optimism’ here, stripping away any element of genuine

triumph by (literally) letting the bottom fall out of the texture? Such

was my impression of Wigglesworth’s reading.

The BBC National Orchestra of Wales is a strong contender

in a field where one might have expected recordings by the St Petersburg

(Leningrad) Philharmonic to show particular commitment. The reality

is that Yuri Temirkanov’s BMG version with the St Petersburg orchestra

is no match for Wigglesworth’s, whilst Vladimir Ashkenazy’s

Decca version with the same orchestra is less rewarding than previous

releases in his fine Shostakovich series (having recorded all of the

symphonies except Nos.13 & 14, Decca tell me that they do not plan

to complete the cycle; worse still, apart from Nos.7 & 11, all of

Ashkenazy’s previous recordings of the symphonies are deleted).

Ashkenazy’s Leningrad is marred by a blunder at bars 531/2

in the first movement where a trumpeter goes bizarrely wrong; this extended

climax seems to be an accident-prone area, as Maxim Shostakovich’s

version is marred by the timpanist entering early at bar 516 and staying

out of time. Both errors may sound trivial when you read about them,

but in performance, played fortissimo, they make one wince.

For me, Bernstein’s two-disc DG set and Wigglesworth’s

new CD are the two most impressive recordings of the symphony; these

interpretations are so different that it would not be an extravagance

if you bought both versions for your collection. Bernstein’s performance

is so imposing that it is difficult to evaluate objectively, as its

monumental weight alone can bowl one over to such an extent as to prevent

one from making balanced relative judgements about other recordings:

if one can put such bias aside, one is likely to conclude that the unique

insights of Mark Wigglesworth make his performance the greater

artistic achievement: the work emerges here as the epic which it is

whilst the spontaneity and sense of new discovery in this reading make

it special.