|

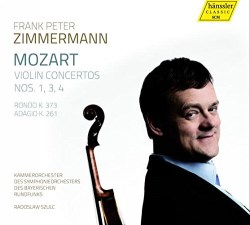

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART (1756 - 1791)

Violin Concerto No. 1 in B flat major, K207 (1773) [20:34]

Adagio in E major, K261 (1776) [6:48]

Rondo in C major, K373 (1781) [5:24]

Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major, K216 (1775) [22:16]

Violin Concerto No. 4 in D major, K218 (1775) [21:45]

Frank Peter Zimmermann (violin)

Kammerorchester des Symphonieorchesters des Bayerischen Rundfunks/Radoslaw Szulc

rec. Herkulessal der Residenz, München, 2014

HÄNSSLER CLASSIC CD 98.039 [76:47]

Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 1 bubbles along cheerily right from its introduction. There are clear, but not overdone, accents from Radoslaw Szulc directing the Bavarian Radio Orchestra’s Chamber Orchestra. Soloist Frank Peter Zimmermann matches them satisfyingly, even though he has the busier task in a showcase of varied figurations. The whole opening movement has an attractive quiet confidence in keeping with the ambivalence of its marking Allegro moderato. Zimmermann’s cadenza, we’re not told whose and Mozart’s don’t survive, has more swagger while also reviewing the full range of material, so you feel you’re getting your money’s worth.

I compared the 2007 recording by Giuliano Carmignola with Orchestra Mozart/Claudio Abbado (Archiv 4777371). At 6:55 against Zimmermann’s 7:42 their emphasis is on Allegro which is more dazzling, the dynamic contrasts of the accents more dramatized and you’re more aware of the wish to display. For the slow movement Szulc sets a warm flowing Adagio which Zimmermann caps with a cantilena full of feeling yet also a clear sense of line. You see where the music is going rather than lingering luxuriously in the moment. Early on he sustains a high B flat while the orchestra's first violins play the melody’s opening. Just the slightest increase in dynamic as he does this vividly conveys a long-breathed sigh. His cadenza briefly but effectively dwells on one example each of the movement’s mix of joy and sorrow. Carmignola is more reflective and exquisite, Abbado’s accompaniment more delicate, but your attention then is as much on the presentation as on the feeling. The finale, timing at 5:36 from Zimmermann and Szulc is lightly articulated yet all high spirits gleefully shared by soloist and orchestra. It's not so much a conversation as a gaggle of gossip, plus an urbanely sparkling cadenza. With arguably a truer Presto, timing at 4:56, Carmignola and Abbado give us greater dexterity to admire but thereby miss Zimmermann's and Szulc’s carefree relaxation.

Violin Concerto No. 3 is markedly different and I like the way Zimmermann and Szulc are different to match. The first movement’s whole feel is more breezy, open air, a joyous projection. There’s also humour, as in the interplay of first and second violins in the second part of the second theme (tr. 6, from 0:50). At this point Abbado conveys the contrast of loud and soft in the second violins more strongly than Szulc but the latter’s more temperate realization makes for a happier atmosphere overall. Similarly with the solo phrases of cascading descents, when the first oboe leads and violin follows. There Szulc’s oboe is vivid yet beauteous where Abbado’s is more racy and skipping. Carmignola and Abbado convey greater drama but Zimmermann and Szulc find more delight. Zimmermann’s cadenza has as much verve as Carmignola’s but more sunshine. Zimmermann is winsome and expressive in the Adagio. It is full of a feeling that has an element of fragility yet is counterbalanced by its sense of the fullness of the musical line which gives it progression as a resolute aria. He doesn’t have Carmignola’s exquisite singing line but at 7:44 Zimmermann’s is a truer Adagio than Carmignola’s 5:59. You therefore get more of a feel of the soloist hovering in the air. Szulc’s busily detailed accompaniment, while less of the gossamer than Abbado’s, is bright and contented. Zimmermann in his cadenza’s ruminations, taking 1:04 in comparison with Carmignola’s 0:33, returns with intense wonder and longing to the movement’s opening phrase. Zimmermann and Szulc’s finale has a winningly stylish combination of lightness of texture and vivacity of expression. The rondo theme is brisk and merry, but has a more gracious tail, a thoughtful, potentially sadder edge which recurs. Zimmerman enters with the first episode, deliciously coy with repeated phrases pleasingly softer. This is an initiative that Carmignola doesn’t provide. Zimmermann’s second episode (tr. 8, 1:40) is cloudier, his central section (3:07) comparably wary before giving way to a combination of earthy dance and dazzling violin cascades in quavers. Carmignola’s central section is more confident, less musing. His dance swaggers but is less folksy.

Violin Concerto No. 4 contrasts a playfully martial and lighter, tripping manner. As if encapsulating both styles, the opening movement’s smooth second theme (tr. 9, 0:32) has a kick at the end of its phrases. Szulc presents this with great élan while Zimmermann gleefully relishes the extra elaboration of the melodic lines once he comes to the spotlight. What a breathtaking display of virtuosity but it's of a type that can be enjoyed rather than wondered at. Moreover, the interplay with the orchestra is finely balanced and crystal clear. To give two examples: from 2:26 the first violins deftly create an obverse to the soloist in a brief falling motif after the soloist’s rising one, then vice versa. From 2:41 we hear the second theme as a falling motif in the lower strings as soloist and first violins have it as a rising motif. Carmignola and Abbado provide a more commanding, compelling progression, but one which allows less scope to enjoy the various new perspectives as they appear. The slow movement, with its rich melody and bluesy touches of harmony, can seem over-indulgent. However Szulc and Zimmermann avoid this by keeping the Andante flowing. The sforzandi are nudged rather than stabbed and there's a caring observation of the partnership between soloist and echoing orchestral instruments. In this way Zimmermann, retrospective but sunny, can be expressive and emotive without being fulsomely so. His cadenza soars and considers, but at a slight distance while his closing solo has great poise. Timing at 5:13 against Zimmermann and Szulc’s 6:00, the less leisurely Carmignola and Abbado pleasingly alternate between bright musing and a more chipper dance style. Zimmermann begins the rondo finale and brings a rather perky, even cheeky manner to its tune. This trails off into something lighter and more cheery as he and the orchestra skip along. The change from Andante grazioso to Allegro ma non troppo is finely graded by Szulc. Lightness is the key here, ensuring Mozart’s quirky pulling about the melodic line remains whimsical. In this account the episodes seem to grow naturally out of the rondo theme, with the soloist introducing a drone in the second (tr. 11, 3:43) for a change of colour. Timing at 6:30 against Zimmermann and Szulc’s 7:01, Carmignola and Abbado provide greater virtuoso display and thrust. Thereby comes a degree more tension and the Andante has to be etched more strongly. I find the sensation of Zimmermann and Szulc sitting back and enjoying everything is a more liveable solution.

Two single movements for violin and orchestra complete this Hänssler Classic CD. In the Adagio in E major, snugly sweet and tinged with nostalgia, Zimmermann dances with immaculate grace, that of an experienced dancer able to evoke a winning fragility. He’s beautifully matched by an introducing and later echoing orchestra whose role is more generally to provide a velvet cushion. Zimmermann supplies a brief cadenza tastefully spiced with double-stopping. The Rondo in C major sports a more sleek, relaxed theme with a luxuriantly scored yet less individualized orchestral backing. The spotlight stays on Zimmermann’s nifty acrobatics in the first episode (tr. 5, 1:00) and a more carefree airborne savouring in the second (2:40). What is it, then, that makes this CD special? The answer lies in its continuous engagement with the music and enjoyment in conveying all its twists and turns.

Michael Greenhalgh

|

|

|