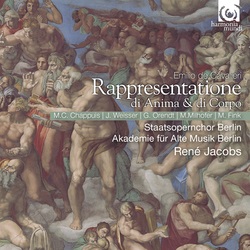

Emilio de CAVALIERI (c1550 - 1602)

Rappresentatione di Anima e di Corpo

Christina Roterberg (soprano) - Angelo Custode; Marie-Claude Chappuis - Anima; Luciana Mancini (mezzo) - Vita mondana; Kyungho Kim - Primo Compagno di Piacere; Mark Milhofer (tenor) - Intelletto, Piacere; Marcos Fink - Anima dannata, Mondo, Secondo Compagno di Piacere; Guyla Orendt - Consiglio, Tempo; Johannes Weisser (baritone) - Corpo

Choir of the Deutsche Staatsoper Berlin, Concerto Vocale

Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin/René Jacobs

rec. 2014, Teldex Studio, Berlin, Germany. DDD

Texts and translations included

HARMONIA MUNDI HMC 902200.01 [38:17 + 54:35]

The present production brings us to the year 1600. It had

been declared a Holy Year and many religious and artistic activities took

place in Rome to express the ideals of the Counter-Reformation. It was also

the year Emilio de Cavalieri's Rappresentatione di Anima e di Corpo

was first performed. This event took place in February in the Oratorio della

Vallicella, the headquarters of the Congregazione dell'Oratorio. This

order had been founded in 1575 by Filippo Neri and was one of the main supporters

of the ideals of the Counter-Reformation.

The Rappresentatione fits into the tradition of the morality play

which goes back to the Middle Ages. It is about an allegorical character who

has to choose which path in life to follow. During the 17th and 18th centuries

many works of this kind were written. Among the best-known is Handel's

oratorio Il trionfo del Tempo e del Disinganno. A late example is

Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebots whose first act was composed by

Mozart.

The Rappresentatione is divided into three acts. The first is devoted

to a dialogue between Soul and Body, which represent two sides of the same

character. In the second act several allegorical figures enter the deliberations.

The Body is especially attracted to the exposition of the delights of worldly

life by Piacere (Pleasure) and two companions. Soul turns to Cielo (Heaven)

who answers in form of an echo that the wise man should fly worldly pleasures;

he who doesn't will die. Then Mondo (World) and Vita Mondana (Worldly

Life) present themselves as glittering figures until Angelo Custode (the Guardian

Angel) undresses them and reveals that they are skeletons, symbols of death.

Intelletto (Intellect) and Consiglio (Counsel) recommend choosing the path

to heaven. In the third act life in Hell is described in drastic pictures

through the testimonies of the Damned Souls. Their fate is juxtaposed with

that of the Blessed Souls in Heaven. As Soul decides to follow the path to

Heaven the choir sings a song of praise: "Let every tongue, every heart

sing praises to my Lord". The work ends with a festa, a celebration

in which all people are urged to rejoice with voices and instruments: "With

songs and smiles give answer to Paradise!"

One of the objectives of Neri's congregation was to make the message

of the gospel understandable for uneducated people, meaning anyone who did

not understand Latin, the language of the Church. This objective finds its

expression in the character of the Rappresentatione. The libretto

was written by Agostino Manni, who maintained close relations with the congregation

and was a student of Neri. The latter had taught him the principles of classical

rhetoric. One of these was docere, to teach. This comes especially

to the fore in the use of the vernacular. Another principle was movere:

the orator should stir the emotions of his audience. To that end Manni chose

the form of a dialogue, and a sharp contrast between opposing characters:

Good vs Evil, Body vs Soul, the Blessed Souls in Heaven vs the Damned Souls

in Hell. The tenor of a work like this explains why these characters are black

and white; there is no place for shades within the individual characters.

Cavalieri concurs with these principles in the way he set the libretto to

music and in his performance instructions. The dialogues take the form of

recitatives which are required to be sung according to the principle of recitar

cantando, speechlike singing. This guaranteed that the text was communicated

to the audience as clearly as possible. Cavalieri also urged the singers not

to add any ornamentation. That could damage the delivery, and also could be

misused by singers to draw attention to themselves and their skills. There

is one exception: Cavalieri has written out coloratura for the Blessed Souls

in Heaven. That can be interpreted as another token of the use of rhetoric:

this way these characters are singled out as they represent what the Rappresentatione

is all about.

The dialogues between the characters are interrupted by choruses which reflect

on the thoughts of the various protagonists, very much in the style of the

chorus in classical theatre. These choruses are all homophonic, again in order

to make the text clearly audible. In order to maximize the impact of the message

Cavalieri wanted his work to be staged, as was the case in the performance

of 1600. In his preface the composer gives detailed instructions as to what

a staging should look like. This aspect has been the reason some musicologists

have labelled this work as the first opera in history. However, considering

its spiritual content it is probably more correct to call it a 'sacred

drama'.

The score leaves the interpreters considerable freedom. That goes in particular

for the use of instruments. Cavalieri urges that the ritornelli and sinfonias

are performed with a large number of instruments, but doesn't specify

which. René Jacobs was guided mainly by a treatise by the composer Agostino

Agazzari of 1607, whereas Christina Pluhar in her recording (Alpha, 2004)

turned to the orchestration of La pellegrina, a play with music which

Cavalieri had put together in Florence in 1589 on the occasion of the wedding

of Ferdinando de' Medici and Christine of Lorraine. There is not much

difference as far as the basso continuo groups are concerned. This is in contrast

to the ensemble of melody instruments, where the present recording includes

recorders which don't appear in Pluhar's recording. Jacobs uses

four violins and four violas; Pluhar has just one violin and no violas.

Another issue is the number of singers involved. Cavalieri recommends one

voice per part for the choruses, or - if the stage is large enough - two per

part. The latter seems to suggest that he wanted the choruses to have a strong

presence. As he wanted the work to be staged it seems impossible for the soloists

also to sing the choruses. Jacobs uses a vocal ensemble, the Staatsopernchor

Berlin, of thirteen voices; Pluhar's ensemble is slightly smaller with

ten singers.

Jacobs is known for taking considerable liberties in his treatment of scores.

He often suggests that his decisions are in line with what the sources say

but they often seem rather inspired by his personal preferences. Fortunately

he behaves very well here. His choices in the vocal and instrumental scoring

are certainly legitimate from a historical point of view. He often works with

singers whose singing is at odds with performance practice of the baroque

era. That is not the case here. There is a bit too much vibrato here and there

but all in all from a dramatic point of view and stylistically the cast is

outstanding. The Staatsopernchor does not specialise in early music, and it

is especially here that the vibrato makes itself felt in that the choruses

are not as transparent as one would wish.

There are a couple of points where Jacobs takes decisions which seem hardly

justifiable. The Rappresentatione opens with a chorus; it has no

overture. In this recording the chorus is preceded by a sinfonia, and here

Jacobs turned to a collection of music by the German composer Johann Hermann

Schein from 1617. Elsewhere another instrumental piece from the same collection

is used as well as pieces by Alfonso Ferrabosco. Cavalieri suggests the inclusion

of sinfonias, but I wonder whether they can be added at random, even in the

middle of an act, such as here in act 3. However, the use of music which is

younger than the date of the original performance is quite odd. The festa

comprises six stanzas; only four of them are printed in the booklet. The score

says that these should be sung by all performers together. However, that is

only the case here with the first and the last; the others are sung by either

five solo voices and some lines by a single voice with instruments. The strangest

decision is that the closing stanza is followed by an instrumental improvisation

over a pedal point which takes about two minutes. The impact of the last stanza

- followed in the score by the word "Laus Deo" - is seriously damaged

by this decision.

It is not easy to translate music for the stage to CD. Obviously many aspects

of a staged performance are lost. That said, Jacobs, his singers and players

and, not to forget, the recording team have done an admirable job bringing

this piece to life in this production. Christine Pluhar's recording

is fine; so is Jacobs', and I don't want to declare one of them

the winner. You can hardly go wrong with either of them.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Previous review:

Brian Wilson

|

||||||