|

|

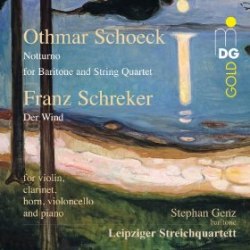

Othmar SCHOECK (1886-1957)

Notturno Op.47(1931-33) [39:25]

Franz SCHREKER (1878-1934)

Der Wind (1908) [10:45]

Schoeck: Stephan Genz (baritone) Leipziger Streichquartett

Schreker:

Stefan Arzberger (violin), Matthias Moosdorf (cello), Marco Thomas (clarinet), Clemens Röger (horn), Olga Gollej (piano)

rec. Konzerthaus der Abtei Marienmünster, Germany, 25-28 January 2013

MUSIKPRODUKTION DABRINGHAUS UND GRIMM MDG 307 1815-2 [50:34]

One of the most interesting products of a series of blind listening reviews some time ago was hearing for the first time the Schoeck Notturno. The excellent performance then was given by Christian Gerhaher (baritone) and the Rosamunde Quartett on ECM. Returning to the work again for this review my initial impression that here is a considerable masterpiece is reinforced and it receives another fine recording.

The Leipziger Quartet has exactly the technical and tonal resources this type of expressionist music demands. Stephan Genz has a lighter voice than Gerhaher but he is fully able to inflect the dark and often shadowed texts with the requisite weight. My main observational comparison between the two versions is that the Rosamundes are willing to push the expressive envelope to a greater extreme while the Leipzigers prefer a greater degree of classical poise and reserve. I can well imagine that some listeners might well prefer this 'held' approach finding the unleashed Rosamundes overly-emoting. Personally, I feel both approaches work but if pushed would opt for the risk-taking Rosamundes. The extended instrumental interlude in the first song demonstrates the differences in approach as well as any: the Leipzigers focusing on the music and the Rosamundes revealing the psychology behind the notes. Elisabeth Decker's interesting liner makes it clear that this was a work which if not autobiographical then certainly has a deeply personal confessional side. It focuses on the 'true' Schoeck: depressive, haunted by a sense of persecution and alienation and beset by emotional insecurities. Possibly at any other time this would seem grossly self-indulgent but written between 1931 and 1933 it happens to chime perfectly with the zeitgeist of the age. What is even more remarkable is how Schoeck, apart from a brief period of study in Leipzig, lived his entire creative life away from the cultural mainstream of Germany yet wrote a work that appealed both to the avant-garde - Berg was an admirer - and audiences alike. Its 1933 premiere was greeted with jubilant applause.

With the exception of the final poem - a setting of Gottfried Keller - the cycle sets poems by Nikolaus Lenau which Decker characterises as 'black Romanticism'. MDG provide full texts in German but with no other translations. Repeatedly one is struck by the integrated nature of the work - the quartet writing goes far beyond that of 'simple' accompaniment. Indeed the voice acts as a fifth instrument; not just a purveyor of text. Also, Schoeck writes in a psychologically complex way eschewing obvious illustrative choices while still striking at the heart of the poetic text. So the nightmare portrayed in the second song is a nightmare of blurred perceptions and slippery fear rather than the hard-edged horror of say Bernard Herrmann's Psycho. The Leipzig Quartet are very good in this movement - beautifully neat playing although it could be argued that this is more a bad night's sleep than a full-blown nightmare. Genz excels with a sense of half-whispered horror flecked by the strangely Will 'o the wisp strings - made all the more disconcerting by its abrupt end. The third movement is characterised by tortuous chromatic writing that rises to a powerful climax. I wonder if the strings could sacrifice a tad of tonal beauty for greater expressive force. The fourth song is the shortest of the cycle - just 2:49 compared to the opening song's 17:04. This is a strangely frozen landscape drained of emotion: "All around, there is a silence and a fading of colour, how gently the wind brushes the woods, cajoling it to give up its withered leaves, I love this placid dying. From here the silent journey begins. The time of love is past, the birds have finished singing, and the dry leaves are falling softly." Although brief, in many ways this linkage of the death of love and the love of death lies at the heart of the cycle and the motivation of its composer. The excellent blog from publishers Boydell & Brewer (called From Beyond the Stave) had an insightful article posted in 2010 Lost in the Stars which explores the work and its origins which I commend to readers.

The closing movement is another stroke of compositional genius. Thanks to the Boydell & Brewer blog I can relate that it is set as a Chaconne and whilst far from being 'happy' Schoeck manages to forge a degree of resolution or at least acceptance from what has gone before. After the chromatic torments of the preceding songs the closing passage of C major has rarely seemed so welcome or calming. This is where the purity of the Leipzig's approach pays dividends - it is one of the most beautifully serene passages of 20th Century music I know; and all the more so for the pain that has gone before. Genz pitches his performance here to perfection with a touching intimacy and a quite beautifully phrased serenity. The more I hear this work the more I am convinced that it really merits the over-used epithet of ‘masterpiece’. I suspect it has not entered the repertoire simply because of the demands it makes of the performers and then how to integrate to work into either chamber or lieder programmes. No such worries need concern a CD collector and I urge readers to familiarise themselves with this remarkable work whether in this version or others.

MDG's engineering help this sense of a musical whole by placing Genz back into the musical ensemble - it’s a wholly sensible and effective choice. Indeed, this is a very well produced, engineered and presented disc. My only caution to readers would be if - like me - they think a more expressionist approach serves this music even better than here. That being said, I am delighted to have this subtly nuanced account added to my collection. All the more so for the ‘filler’ of Schreker’s short ballet Der Wind. This 1908 commission was a spin-off from his Der Gerburstag der Infantin after Oscar Wilde. One normally associates Schreker with rather feverish narratives and opulent large-scale scoring. This sub-eleven minute piece for a mixed quintet of instruments is something of a surprise. It is quite charming and well-played but important to note it was not published in the composer’s lifetime since, as the liner puts it, “perhaps he no longer attached importance to the work because he was busy creating his first opera Der ferne klang.” That opera fully deserves attention so hard not to view Der Wind as a minor work at best. After the emotional wrack of the Schoeck the detached objectivity of the Schreker could be heard as either soothing balm or unnecessary appendix. Interestingly, I enjoyed it much more as a piece the time I listened to it alone. In that instance it gains a curious near-impressionism quite unlike other Schreker I know. The scenario is very simple - a gentle wind blows through some trees, a brief storm occurs and the wind dies down. Schreker makes full use of all the illustrative capabilities of the keyboard, in particular leaving the other instruments to carry the melodic/motivic roles. The cello has more of a bass than tenor role giving the work a firm underpinning. In this way the instrumental line-up mixing strings and wind/brass backed by a piano hints at the standard small orchestra rather than a chamber group. Admirers of this composer will enjoy hearing this work and again the MDG engineering is very good at creating a detailed, unified and satisfying sound-picture; balancing a horn against a piano and violin is never easy.

Even with the filler, this is a rather short-playing disc, only just breaking the fifty minute mark. There is a strong argument that the musical quality is high and needs no ‘extra’ value in the form of additional music. That being said there are other versions on the market which do just that, potentially giving listeners the best of all worlds.

An enjoyable disc of very fine music in sensitive and subtle performances. Possibly not a first choice purchase but worth consideration.

Nick Barnard

|

|

|