|

|

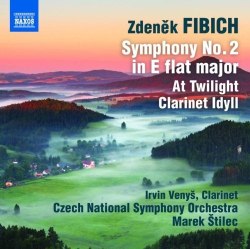

Zdeněk FIBICH (1850-1900)

Symphony No 2 in E flat, Op.38 [40.16]

At twilight, Op.39 [16.24]

Idyll in B flat for clarinet and orchestra, Op.16 Selanka [6.47]*

*Irvin Venyš (clarinet)

Czech National Symphony Orchestra/Marek štilec

rec. CNSO Studio No 1, Prague, 23 October and 9 November 2012

NAXOS 8.573157 [63.36]

In their early days Naxos deliberately avoided any duplication in their catalogues, preferring instead to expand the recorded repertory with their commendable exploration of music which lay further off the beaten track. This policy soon became unsustainable, and newer recordings of existing titles have become regular features in the lists of new releases from this source. Such recordings have however generally been confined to the core repertory, and it comes as something of a surprise to find that Naxos are now producing new recordings of Fibich’s symphonies to replace their older releases with the Razumovsky Sinfonia (symphonies 1 and 2 on Naxos 8.553699; originally issued on their sister label Marco Polo). However the rationale behind this is immediately apparent when it becomes clear that this is Volume 2 of an exploration of the complete orchestral works of Fibich (see note on the Fibich website), and that the new recordings enshrine the results of new research into the performance material with the correction of a “number of errors” and the observation of “all the repeats prescribed by Fibich.” This makes a considerable difference to the finale of the symphony, here a full four minutes longer than in the Marco Polo release or the recording by Neeme Järvi for Chandos (review). Indeed all the movements here are decidedly longer than in either the Chandos or Marco Polo recordings.

That is due in part to the performance itself, which sets out at a fairly comfortable speed although it generates plenty of drama with pointed playing from an orchestra who understandably display more familiarity with the music than Järvi’s Detroit Symphony. This pays real dividends in the second movement Adagio, where the massed violins produce a volume of rich romantic tone which suits the music ideally (as at track 2, 3.45). The third movement scherzo is not really Presto as marked, but štilec’s ländler approach brings out clearly the parallels with early Mahler as well as emphasising the manner in which the opening trumpet fanfare recollects the finale of Dvořák’s Eighth Symphony written some three years earlier. The orchestral playing, full of character, has quite enough delectable pointing of phrases to make up for any lack of sheer animal excitement.

In view of the controversy which has raged on the MusicWeb International message board during recent weeks over the matter of repeats in the Dvořák symphonies, it is perhaps noteworthy that Fibich seems to have had no compunction about observing these; indeed the booklet notes inform us that the omission of these repeats “which over the years [have] crept into professional performances” were never “authorised by the composer”. Here we have the full repeat of the opening material of the finale - which explains the considerable increase in duration over the Järvi performance - and although it does not really add anything to our appreciation of the music the increased duration of the movement does help to provide a more substantial conclusion to the symphony.

The symphonic poem At twilight is described by Richard Whitehouse in his booklet note as “Fibich at his most Wagnerian in matters of harmony and orchestration”; indeed the work makes a decided contrast to Dvořák’s folk-influenced works in the same genre. There are also overtones of Liszt and rather startlingly Delius (as at track 5, 6.15) where the music almost anticipates the Walk to the Paradise Garden. This symphonic poem is not to be confused with a short piece with the same title - although sometimes called Summer evening - which has over the years become one of Fibich’s best-known works, often featuring in collections of ‘light classics’; there are even recordings by the Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra and Mantovani. The full-length symphonic poem is much more of a rarity, and this performance is excellent enough to withstand the most exalted competition. The recording is rich and full, giving full justice to the luscious scoring.

The Idyll is even less well-known. This appears to be the only recording in the current catalogues. It therefore makes a valuable bonus to this disc. Although Fibich wrote no concertos, he did produce several concertante works, and the Idyll is an orchestration of a piece originally written for clarinet and piano. It is a charming lightweight trifle, played here with real feeling by an excellent soloist and a deliciously responsive orchestra. Not a great discovery, but a piece of value nonetheless despite its somewhat abrupt ending.

The studio where these recordings was made has a slightly claustrophobic sound, which cannot compare with the more resonant acoustic provided for Järvi by Chandos. This is only troublesome in the noisier passages of the finale of the symphony, and elsewhere creates no problems. The use of scholarly versions of the music, moreover, gives this new CD a real edge over its rivals, and one looks forward with pleasure to further issues in the series. The music of Fibich is yet another example of a composer who has tended to be lost to sight outside his native Bohemia. Major works like the cycle of three melodramas Hippodamia show him to be a writer of no mean accomplishment, who despite his early death by no means deserves to be overshadowed by his contemporaries Smetana and Dvořák. Indeed those who enjoy the symphonies of the latter will find much to interest them here too.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

Other reviews

Volume 1 in this series: Rob Maynard and Nick Barnard

Christopher Howell’s review of the classic Sejna set from Supraphon

|

|

|