|

|

Fritz KREISLER (1875-1962)

Praeludium and Allegro in the style of Pugnani [5:05]

Apple Blossoms: Syncopation (1919) [2:12]

Schön Rosmarin [2:07]

Liebesleid [3:46]

Liebesfreud [3:11]

Polichinelle [1:40]

Tambourin chinois, Op. 3 [3:56]

Melody in the Style of Gluck, Melodie from Orfeo ed Euridice [3:24]

March of the Toy Soldiers [1:53]

La chasse in the style of Cartier [2:01]

Caprice viennois, Op. 2 [4:00]

Allegretto in the style of Boccherini [3:17]

Danse espagnole for violin and piano, after Falla's La vida breve [3:25]

Slavonic Dance No. 2 for violin and piano in E minor: transcription of Dvořák's Slavonic Dance No. 10 [4:42]

Apple Blossoms: Miniature Viennese March (1919) [3:15]

Recitativo and Scherzo-Caprice for Violin solo, Op. 6 (1911) [4:58]

The Devil's Trill, for violin and piano: transcription of Tartini's Sonata [15:58]

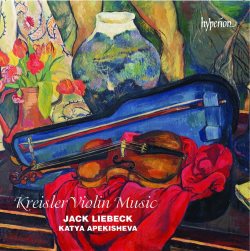

Jack Liebeck (violin): Katya Apekisheva (piano)

rec. April 2013, St. George’s, Brandon Hill, Bristol

HYPERION CDA68040 [68:53]

There are seventeen Kreisler originals or arrangements in this release from Jack Liebeck and Katya Apekisheva. They range from the deliciously brief Polichinelle to the finger-straining drama of the arrangement Kreisler made of Tartini’s Devil’s Trill sonata, which occupies sixteen minutes of this 69-minute recital. Liebeck is not necessarily in competition with Kreisler himself, given that for the most part many listeners may not have come Kreisler’s recordings, and certainly not the precious acoustic recordings which represent him in the full flower of his youthful genius. Nor really should one necessarily point to players such as Mischa Elman, Oscar Shumsky or Henryk Szeryng, to cite just three stylistically self-aware players of past generations who have essayed a swathe of Kreisler on disc – Shumsky in particular whose set is now on Nimbus. On the other hand it is useful sometimes to remember the performances of older players, especially colleagues of Kreisler’s, to document whether performances seem receptive to the ethos or occupy a rather less certain stylistic ground.

All this is a preface to Liebeck’s recital with Apekisheva which strikes a resilient, smoothly confident air. The Praeludium and Allegro, a piece Kreisler famously didn’t record, might for need a touch more metrical freedom, though the obverse is a lack of flabbiness. The passagework is well shaped, though the end is a little prosaic. Liebeck’s approach throughout is suavely virtuosic. Liebesleid has a clear-eyed modernity, a resilient and adroit musicality, and those seeking a replication of the composer’s expressive devices or indeed those of a host of similarly expressive players will search largely in vain. Tambourin chinois is again pristine if a touch over-insistent rhythmically. The Toy Soldiers’ March can often be played with quite a smile, though here that’s not really the case. However, the duo takes a fine tempo for the Recitativo and Scherzo, which Kreisler dedicated to Ysaÿe. It’s one of his most challenging and impressive works in the genre and fortunately the performance is fine - excellent tempo, digital precision and firmly musical. When one reaches the arrangements Liebeck relaxes attractively into the Gluck and digs into the Dvořák. The recital ends with a forthright and buoyant account of the Tartini, not at all circumspect or finicky. This is resilient playing indeed.

It’s also playing that cannot - and does not try to – evoke Kreisler’s own performance practice and his own sound world. This applies as much to rubati as to matters like glissandi and vibrato. Sometimes therefore, Liebeck sounds sleekly remote from the ethos. On the other hand, the playing itself is vitalising and unabashed. He doesn’t make slides when they feel self-conscious, so tends not to make them. He stands his own ground, and the results do generate a fruitful tension between the Kreislerian model and the modern performance.

Jonathan Woolf

|

|

|