|

|

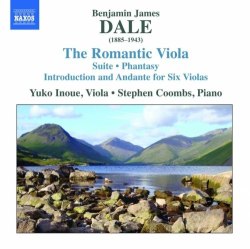

Benjamin DALE (1885-1943)

The Romantic Viola

Suite for Viola and Piano in D major Op.2 (1906-7) [33:11]

Introduction and Andante for Six Violas Op.5 (1911) [10:38]

Phantasy for Viola and Piano Op.4 (1910) [20:05]

Yuko Inoue (viola), Stephen Coombs (piano)

Tinghan Liu, Wenhong Luo, Richard Waters, Clifton Harrison, Anna Lusty (violas - Introduction and Andante)

rec. Duke’s Hall, Royal Academy of Music, London, 6, 20, 23 July 2012

NAXOS 8.573167 [63:54]

"Unashamedly Romantic" is a phrase used by violist Yuko Inoue in her informative liner-notes to describe much of the music written by British composers for the inspirational violist Lionel Tertis. Certainly that is the case here with three substantial scores written by Benjamin Dale in the first decade of the 20th Century. Dale was another name borne up by that extraordinary flourishing of compositional talent that happened in British conservatoires from around 1890 - the period that has become termed "The English Musical Renaissance". Together with contemporaries such as Bax, Bowen, Coates, Bantock and Holbrooke, Dale studied at London's Royal Academy of Music primarily with Frederick Corder for composition. Dale and his close friend York Bowen were two to make the quickest impact with their strikingly confident, appealingly romantic large-scale works. Yet they were two whose music most rapidly fell off the performing radar as the century progressed and their music seemed more and more dated.

A century further down the line and the minutiae of the progressive pecking order seems less important. So when presented with performances of such commitment and high technical accomplishment as those here one can sit back and enjoy the musical delights offered. Inoue fairly makes the point that Dale probably did not fully exploit the extraordinary potential he showed as a student. Interned in Germany - where he happened to be holidaying in 1914 - throughout World War I he seems to have produced remarkably little from his return until his death at the age of 58 in 1943. This is especially curious given the large and confident scale of his early works. Consider the two main works here; the Suite - running to thirty three minutes - and the Phantasy just over twenty, neither are exactly the product of a shy retiring miniaturist.

For a student work the opening Suite - his Op.2 after his remarkable Op.1 Piano sonata recorded to great effect by Mark Bebbington - is both strikingly confident and musically assured. The piano's opening gesture leaps heroically in the best Romantic tradition. The tone for both the music, the quality of the performance and the technical aspect of the recording is set in these opening bars. Pianist Stephen Coombs has, it seems to me, exactly the right temperament for this style of music - big rhetorical gestures tossed off with complete aplomb. Producer/engineer Michael Ponder - no mean violist himself in his day - gives the piano a realistic balance. By this I mean that there are occasions when the sheer scale and activity of the keyboard writing threatens to overbalance the viola. Personally, I prefer it this way as it is an accurate reflection of the score as written. For the viola to be clearly audible at every moment would require a synthetic balance. The fault, if fault it is, lies with the young composer. Inoue in her note mentions that the first two movements were particular favourites of Tertis - he requested that they were orchestrated. Wikipedia mentions the second and third as the orchestrated pair. My guess would be Inoue is right simply on the grounds that the opening movements are better. Certainly there is a sweep and exultant energy to the writing that cries out for a larger canvas; not that Inoue or Coombs lack either quality. This music has been collected together at least twice before; on Dutton and on Etcetera (KTC1105). The former has exactly the same programme but adds the transcription of Dale's English Dance by York Bowen. The latter omits the Introduction and Andante, replacing it with two piano pieces. I have not heard the Dutton disc but do know the Etcetera performance from Simon Rowland-Jones and Niel Immelman. Broadly speaking theirs is a calmer, broader approach - which adds three minutes to the Suite and two to the Phantasy. As ever, there is a sense of swings and roundabouts but I respond more enthusiastically to the sheer drama of Inoue/Coombs.

For a half-hour work, the Suite just about manages to not outstay its welcome - but one does rather think that had Dale composed into older age he might well have found a more compact way of saying much the same to ultimately greater effect. Strangely I found this to be even more true of the shorter Phantasy. This is another work inspired/produced as a response to the William Cobbett prize for single (linked) movement chamber music. In direct comparison to other works written for the prize it feels rather diffuse and meandering although with passages of great beauty. Again Inoue and Coombs give it a performance of total conviction well recorded. The other work is a real oddity in the repertoire. I'm not sure I can think of any other concert work for six violas. The impulse to compose it was again Tertis who wanted a piece to illustrate a lecture he was to give in 1911 about the rise of the contemporary viola. The result was this work premiered by Tertis and five of his pupils from the Royal Academy of Music. How wonderfully apt then that Inoue - a current professor at the same institution - leads a performance given by her own students. A very fine group of players they are too. Michael Ponder skilfully places the six instruments across the stereo spectrum so you can clearly hear how well Dale distributes the musical interest. Certainly there is no sense of a lead part - Inoue one assumes - and five faithful acolytes. Dale got around the potential problem of "sameness" by employing a wide variety of string techniques as well as scordatura tuning - one player tuning their lowest string down a perfect fourth to a low G to allow for a final sonorous A flat chord. I'm sure this was a hugely enjoyable and rewarding experience for the young players who do themselves and their teacher proud. Again, as to its real enduring worth as a stand-alone piece as opposed to a curio, I am not so sure.

Adding to the 'rightness' of this is the use of the Academy's famous Duke’s Hall as the recording venue. This same hall will have seen the debut performances of many of Britain's finest young players and composers of the last century and more. However, that same venue does lead to the biggest single issue I have with the disc - the dreaded Marylebone Road. This is one of London's main arterial routes that runs right outside the hall. For all Ponder's skill and the thickness of Dale's writing whenever the dynamic of the writing drops the incessant rumble from the road is all too clear to hear - especially on headphones. We have all become so accustomed to the sepulchral silence of CD that this level of background noise comes as something of a shock. In the days of LP it would have been happily swallowed up by rumble and surface noise heard via my moderate quality record deck. On repeated listening I was less aware overall but there are key passages of considerable poise and beauty whose impact is diminished by the presence of the A40 westbound.

In its own right this is an excellent disc that further enhances the Naxos catalogue of British chamber music. Much as I respond to this music, I do believe that its relative neglect is in fact a fair reflection of its interesting but minor status. Without a shadow of a doubt other British contemporary composers were writing music of greater depth and enduring value. That being said, I hope Inoue continues to explore similar repertoire together with Coombs and gets the opportunity to record whichever movements of the Suite Dale orchestrated. Perhaps Dutton could commission Anthony Payne or Martin Yates to orchestrate the third.

Nick Barnard

|

|

|