In the year in which we celebrate the 100

th anniversary of Panufnik’s birth and commemorate the 20

th anniversary of Lutosławski’s death it is good to know that in the case of Panufnik at least there have been a good number of releases of his music

(see r

eview

of the Chandos release of the quartets). It was well represented at this year’s BBC Proms. Lutosławski was also covered and last year for his birth centenary there were a number of discs released. It would be fair to say that the music on this disc cannot be described as ‘easy on the ear’; the listener has to put in some effort, giving it total concentration, before it reveals itself in its fulsome brilliance.

The bulk of Panufnik’s first string quartet which he wrote aged 62 is extremely spare in nature. It only appears to come to life in its closing passages in a postlude that Panufnik added following the quartet’s first performance. His second quartet has an interesting inspiration; when Panufnik was on childhood holidays he discovered that he very much enjoyed putting his ear against telegraph poles and listening to the vibrations caused by the wind. He even put this experience down as his first excursion into the creative process in that he used his musical imagination for the first time. This is how this quartet gets its subtitle ‘messages’. It makes sense to keep this back story in mind while listening since there are plenty of representations of those ‘messages’ within it.

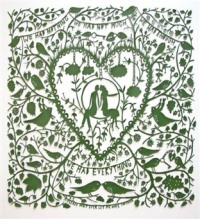

The third quartet, one of Panufnik’s final works, again draws its inspiration from his homeland in that its subtitle ‘wycinanki’ refers to an extraordinary example of Polish folk art: the incredibly intricate designs that are made by paper-cutting. Panufnik himself described them as “symmetrical designs of magical abstract beauty and na´ve charm” which is a pretty good way of describing the quartet. I’ve never done this before but an example of it here would help to illustrate the well-spring of quartet’s origins.

It is this kind of inspiration from his Polish homeland, that he eventually felt compelled to leave, that permeates all of Panufnik’s music whether, on its sleeve or more subtly, more hinted at than ‘in your face’. If any reader is unfamiliar with his works then they could do no better than explore his

Sinfonia Rustica which is chock-full of folk references and would be an excellent first foray into Panufnik’s world. It also serves as a good preparation for the more ‘avant-garde’ works.

Lutosławski’s only string quartet also originates from his experimental period during which he was considered a leading composer of the European avant-garde. Nevertheless it could be argued that it is ‘more tuneful’ than Panufnik’s with more activity and less sparseness about it. However, there is an inner beauty in all these four works. It only requires the listener to give it time before that beauty, if not immediately evident, works its magic and shows how great these two composers were. They hold an important place in the development of twentieth century music.

I come to all these works for the first time. Already an admirer of both Panufnik and Lutosławski, I yet had no aural benchmark against which to measure the performances. I can however say that they are utterly compelling and the best possible case is made for them. The intense concentration necessary is evident at every turn and I’m sure Michael Tippett would have felt both pleased and honoured that this quartet took his name for it. Once again Naxos deserves congratulations for its continued commitment to releasing discs of works that are both important yet unlikely to sell in the same quantities than yet another Beethoven fifth or Albinoni adagio.

Steve Arloff