|

|

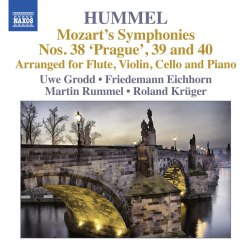

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART (1756-1791)

Arrangements for flute, violin, cello and piano by Hummel

Symphony No. 38 in D major, ‘Prague’. K.804 (AE 546) [25:39]

Symphony No. 40 in G minor, k.550 (AE 547) [23:33]

Symphony No. 39 in E flat major, K. 543 (AE 548) [26:11]

Uwe Grodd (flute), Friedemann Eichhorn (violin), Martin Rummel (cello), Roland Krüger (piano).

rec. 14-16 Jan., 2010, Schloss Weinberg, Kefermarkt, Austria.

NAXOS 8.572841 [75:29]

Hummel’s arrangement removes the universality of Mozart’s

symphonies and renders a certain intimacy to each piece. In this CD,

the listener can appreciate what Eduard Hanslick describes as ‘the

beautiful in music’. Through these performances Hummel’s

emotional response to Mozart is felt. In lieu of Hanslick’s

theories posited in his book entitled Vom Musikalisch-Schönen,

Hummel’s art is recognised: ‘above all, as producing something

beautiful which affects not our feelings but the organ of pure contemplation,

our imagination.’

Hummel’s adoration and respect for Mozart is evident in these

almost unwavering arrangements; only altering a few stylistic trends,

so as to be in keeping with the times, Hummel’s interpretations

are eloquent gestures to his idol. In keeping with the self-conscious

and at times introverted Romantic spirit, Hummel strips away some

ornamental embellishments to produce a minimalist and reflective approach.

As a friend of the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Hummel appears

to be ‘Making music out of beauty, / With a question hidden

deep’ (April). These pieces form an homage to the majesty

of Herr Mozart; so much so that one can imagine Hummel using Goethe’s

words to confess that:

In my music’s echo

The starry host appear,

Eternal feelings, bless, now:

Sleep! What would you more?

(Night Song)

The quartet work well in the more sprightly passages — the tempo

is generally a little faster than when recorded as a symphony —

where the individual instrumentalists seem to meld effortlessly. However,

in the more pensive and slower passages, such as the slow opening

to the first movement of the Prague, the musicians sometimes

lose their point of connectivity and sound slightly out of kilter

and rather too tentative. As a pianist himself, Hummel dons the piano

with an added sense of importance. At once forthright and yielding,

its presence is both stimulating and consoling for both musicians

and listeners. In this recording, Hummel’s sense of coherence

and finely-tuned attentiveness is subtly recognised by Roland Krüger

who is allusive and suggestive rather than declamatory. Krüger

gives insightful impressions and glimpses into the tensions between

the Mozart originals and Hummel’s savvy interpretations. Often

given the role of provocateur, Hummel’s piano-line arrangement

in particular is intriguing and exciting. Unfortunately, this zesty

character is sometimes overshadowed by Uwe Grodd’s occasionally

wafty and glib swathes. Grodd performs best when structurally restrained

within the clipped staccato framework of the piano. When performing

the Presto of Symphony No. 38, Rummel unfolds the cello’s rustic

and smooth timbres which speaks of the attitude of the piece as a

whole. The final movement jostles between vigorous outbursts and lyrical

passages where the instruments both echo and offer contrasts to the

initial motifs.

Originally composed on 25 July 1788, Mozart’s ‘Great

G Minor Symphony’ arranged by Hummel turns this often hummed

and whistled piece into something more contemplative and internal.

Described by Robert Schumann as possessing ‘Grecian lightness

and grace’, under Hummel’s grounding hand, this loses

its loftiness and becomes somewhat earthly. Most noticeably, the exchanges

between piano and cello in the Allegro molto transform a

supine melody into something acoustically coloured and textured. In

the Finale (played allegro assai), the ensemble

maximise the tension within rest beats and unpick Hummel’s exquisite

arrangement, highlighting yet merging the jagged tones of each instrument.

The final piece, the Symphony No. 39, bursts forth with eagerness.

To follow Christian Schubart’s definition from his Affective

Key Characteristics, this is a piece which tells a story ‘of

love, of devotion, of intimate conversation with God’. By contrast,

in the Minuetto, a sense of youthful gaiety and femininity

pervades. Acting as an energetic interlude, this movement is played

with diction and delight. The quartet is in the faster movements both

careful and precise. At times the musicians seem marginally lacklustre;

however, the overall impression is one of commensurate technical ability

and good intentions.

Lucy Jeffery

Previous review: John

Sheppard

|

|

|