|

Support us financially by purchasing

this disc through MusicWeb

for £10.50 postage paid world-wide.

|

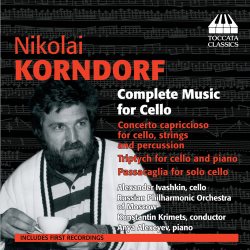

Nikolai KORNDORF (1947-2001)

Complete Music for Cello

Concerto capriccioso for cello and percussion (1986) [28:55]

Triptych for cello and piano (1998-99) [23:26] ¹

Passacaglia for solo cello (1997) [23:49]

Alexander Ivashkin (cello)

Russian Philharmonic Orchestra of Moscow/Konstantin Krimets

Anya Alexeyev (piano) ¹

rec. August 2001, Studio One, Moscow Radio House (Passacaglia); November 2005, live at the Great Hall of Moscow Conservatoire (Concerto capriccioso): December 2006, live at Lazaridis Theatre, Perimeter Institute, Waterloo, Canada (Triptych)

TOCCATA TOCC0128 [76:24]

Russian-born composer Nikolai Korndorf died in his Canadian home in 2001, whilst playing a game of football with his son. He was still only in his early 50s. He had taught composition at the Moscow Conservatoire, where young radicals apparently called him ‘our Rimsky- Korsakov’, and received critical acclaim for a series of works including his opera (called MR – Marina and Rainer) and his Third Symphony but in 1991 had emigrated, continuing to produce challenging new music. This 2012 Toccata disc presents two premiere recordings, both of which are live (the Passacaglia has been recorded before) but it must also now serve as an memorial for the cello soloist and friend of Korndorff, Alexander Ivashkin, whose death was recently announced.

Ivashkin, knowing Korndorff - and so many others - so well, writes booklet notes that dwell on a number of salutary themes and they make for rewarding reading, both biographically and for the light they shed on Korndorff’s compositional directions. The Concerto capriccioso for cello and percussion was composed in 1986 but had to wait until January 2004 for its première, which was given by Ivashkin in Winnipeg. This live Moscow performance followed nearly three years later in December 2006. Ivashkin advances ideas about its links to ritualistic Russian paganism and elements of minimalism, and the percussive elements do indeed sound reminiscent of Buddhist ritual. But it can be listened to perfectly well as a sonic exploration in its own right in which tinkling percussion and yearning quasi-improvisatory cello offer a sense of rapture and vocalised intensity. As the music develops a sense of the processional is built up, and Korndorf delivers a powerful distillation of ecstasy to end the long first section. The second movement is half the size of the first and has a very different character. The minimalist element, seemingly locked with the Buddhist, is soon accompanied by a Rock beat as the music not merely swings between genres but actively conjoins them.

The Triptych for cello and piano was completed in 1999 and is in three movements. The cello plumbs the depth and there’s a strong element of reflective, in fact melancholic writing in the opening movement, marked Lament, which takes on a highly updated ‘Baroque’ quality. The central movement comes as a complete contrast – in fact it’s a transcription taken from Korndorf’s orchestral work The Smile of Maud Lewis, completed a year earlier. The piano charts a repetitive course whilst the cello pirouettes and deftly turns above it. Russian Orthodox ritual suffuses the finale, citing a specific hymn, before ending in a kind of jubilation. The only one of the three pieces to have been recorded before is Passacaglia, a powerful 24-minute work for the solo cello. It was written for Ivashkin and is a kind of palimpsest of theDivine Comedy in which the cello is the narrator. Eerie microtones, finger taps on the body of the cello, and spoken text (by the cellist) fuse together. The col legno effects and thumps attest to the terse descriptive power invoked, and the ascent to the Paradiso’s chorale is hard-won. Dante’s relevant Cantos are reprinted in the booklet.

The performances throughout are hugely committed and sensitively shaped, with recording quality to match – this despite the fact that two were recorded live and there are three different recording locations. It is fitting to salute Ivashkin’s profound dedication to this body of work, and fitting also to reflect on Korndorf’s musical and cultural breadth of reference in these highly individual and often solemnly beautiful works.

Jonathan Woolf

|