|

|

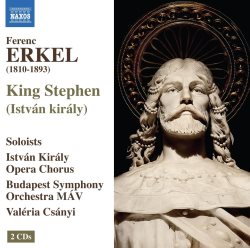

Ferenc ERKEL (1810-1893)

King Stephen (István király) (1884) [142.00]

János Gurbán (baritone) – King István; Jutta Bokor (contralto) – Queen Gizella; Zoltán Nyári (tenor) – Prince Imre; Zsuzsanna Bazsinka (soprano) – Princess Crescimira; Kázmér Sárkány (baritone) – Vazul; Tamás Daróczi (tenor) – Sebös; Jolán Sánta (contralto) – Jóva; Ildikó Szakács (soprano) – Zolna; Tamás Szüle (bass) – Barang; Ferenc Valter (bass) – Gellert; Ákos Ambrus (baritone) – Péter; Sándor Kecskés (tenor) – Hunt, Prince Endre; János Fátrai (baritone) – Pázmán, Béla, Csanád, Asztrik; Dömötör Pintér (bass) – Vencelin, Levente, Soldier, Herald; King Stephen Opera Chorus; László Deák (organ)

Budapest Symphony Orchestra/Valéria Csányi

rec. Rottenbiller Street Studio, Hungaroton, Budapest, 26-27 August 2012

NAXOS 8.660345-46 [75.11 + 66.49]

It might seem odd that the great Hungarian composer of the nineteenth century, Ferenc (or Franz) Liszt, never turned his hand to opera again after his teenage Don Sanche. It was not that he was averse to the medium; under his aegis major operas by Wagner, Berlioz and Cornelius were all given model productions at Weimar. Nor was he, like Brahms, wedded to traditional classical forms, having pioneered the dramatic use of the symphonic poem. It may well be however that he did not wish to enter into competition with the extremely successful Hungarian operas of his friend — and colleague as director of the Budapest Music Academy — Ferenc Erkel. These dominated the stage in that country during the period of thirty-six years from 1838 when Erkel was director of the opera company at the Hungarian National Theatre. Not that Erkel’s operas were anything as musically individual and pioneering as the works of Liszt, Berlioz or Cornelius – let alone Wagner. Erkel was quite content to continue ploughing the furrow of grand opera in the style of Meyerbeer and Spontini, who dominated stages in central Europe just as much as in France during the years from 1838 onwards. It was only in the years after 1865 that the works of Wagner began to appear on German stages, and even then their progress was slow. By the time that the Wagnerian ‘music drama’ had established itself following the first Bayreuth Festival in 1876, Erkel had retired. Then it was the growth of Wagnerism during the following decades that effectively confined Erkel’s operas to the repertory in Hungary and precluded any expansion into opera houses elsewhere. Only one other opera by Erkel features in the current catalogues, and that recording of Bank Bán, like this new recording of King Stephen, comes from Hungarian sources; a 1980s recording of Hunyádi László, also from Hungary, was recently reissued by Brilliant Classics (94869).

King Stephen was originally projected by Erkel as an opera as early as 1846. In the event the work did not reach the stage until 1885 when it was a huge success. It orchestration was partly completed by the composer’s sons. After Erkel’s death his sons further expanded the score, adding fourteen new items. After revivals in 1910 it fell from the repertory until the 1930s, at which stage it was cut to half its length. For this recording the creators restored Erkel’s original score, restoring the 1930s cuts but removing the later accretions. We are told in the informative booklet notes by István Kassai - for which I am indebted for this potted history of the work’s performance history - that the extensive ballet music in Act Two, which was not given at the opera’s 1885 première, has been omitted. One might perhaps regret this, since Erkel’s dance music in his other operas is a highlight of those scores. As it is, we have two very full CDs which may well be sufficient for most listeners.

The opera appears to be based on the same source as Beethoven’s King Stephen, but employs a different play as the foundation of the action. Beethoven’s incidental music to Kotzebue’s play is known nowadays principally for its overture. Erkel, employing a play by Antal Varádi, dispenses with an overture altogether, opening instead with a rather conventional chorus depicting a session of the Diet of Hungary. The convoluted story portrays a conflict between an oath undertaken to God and filial obedience. The characters are cardboard in their actions and motivations. The conflict between the Christian and pagan worlds has none of the immediacy that one finds in Wagner’s Lohengrin of over thirty years earlier. On the other hand, the stately music for the wedding procession (CD 1, track 10) clearly demonstrates that Erkel was familiar with Wagner’s work. Also, at the beginning of Act Three (CD 1, track 12), the wedding chorus is far too closely imitative of Wagner to be comfortable. Erkel has a nice line in pageantry, although his occasional attempts at nature music are very conventional but the grand choruses in Act Four are blazingly impressive in the manner of Meyerbeer.

The deficiencies of the music cannot be laid to the blame of the performers, who are generally fine. The exceptions are blowsy and curdled Zsuzsanna Bazsinka, the very plummy-sounding and wobbly Jolán Sánta, who is a decided trial early on (for example in CD1, track 3), and some rather unsteady voices in smaller comprimario parts. There are no great undiscovered stars in the rest of the cast, but all engage well with the text and manage their lines with grace and poise if with no great sense of dramatic involvement. There are only two solo arias in the score: Tamás Daróczi shows some strain in his Billowing waves which opens Act Two (CD1, track 5), and Bazsinka is unattractive in her Just sing (CD 2, track 7), negotiating the sometimes elaborate music clumsily and sounding unpleasantly shrill on the high notes. On the other hand Ildikó Szakács is much more satisfactory in her aria with chorus Here is the place which opens Act Four (CD2, track 4). It’s one of the best numbers in the score. Zoltán Nyári in the other tenor role has a nicely focused voice, but his duet with Bazsinka (CD 1, track 13) is spoiled by her persistent unsteadiness.

The recorded balance, with the soloists in front of the orchestra and the large and enthusiastic chorus placed somewhat in the background, is very studio-bound, but the acoustic is nicely resonant and imparts plenty of body to the recorded sound. There is, appropriately in a work about the life of a saint, plenty of music for the organ, and László Deák deserves his independent credit even though the writing has none of Liszt’s ground-breaking virtuoso writing for the instrument.

There are no other recordings of the opera in the catalogues, and given the textual complications it is unlikely that any earlier historical performances which might emerge at some future date would begin to do justice to the work. One might regret that the libretto - commendably available on the Naxos website - is available in Hungarian only, but a very full two-page cued synopsis enables the non-Hungarian listener to keep abreast of the discursive developments of the plot.

Erkel’s King Stephen is assuredly no undiscovered masterpiece, but one is nevertheless grateful to Naxos for making it available and it certainly has interest.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

|

|

|