|

|

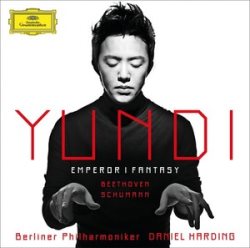

Ludwig van BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat major, Op. 73 Emperor [38:51]

Robert SCHUMANN (1810-1856)

Fantasy in C major, Op. 17 [28:02]

Yundi (piano)

Berliner Philharmoniker/Daniel Harding

rec. Berlin, Teldex Studios, January 2014 (Schumann); Berlin, Philharmonie,

January-February 2014 (Beethoven)

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 481 0710 [67:01]

I first came across Yundi several years ago when I discovered his recording of piano concertos by Chopin and Liszt. An enjoyable listen, I went on to acquire his Liszt recital, which contained a superb Sonata in B minor. Another highlight was a breathtaking Verdi/Liszt Rigoletto Paraphrase. The CD was later named ‘Best CD of the Year’ in 2003 by the New York Times, and deservedly so.

Li Yundi was born in 1982 in Chongqing, China. He is from a non-musical family. At the age of eighteen in 2000, he became the youngest pianist to win the International Frederick Chopin Piano Competition. He was later the subject of a documentary: ‘The Young Romantic: Yundi Li’ in 2008. Now in his early thirties, Yundi, as he now promotes himself - his first discs were marketed under the name Yundi Li - has decided to explore the works of Beethoven. Last year I reviewed his first foray into this repertoire with a disc of three ‘named’ sonatas, the Pathétique, Moonlight and Appassionata. Despite some minor reservations, I was, on the whole, favourably impressed.

Here, he performs Beethoven’s largest-scaled concerto, the magisterial fifth, known as the Emperor. To follow it, he turns his attention to Robert Schumann and what for me is his greatest solo piano work, the C major Fantasy, Op. 17. The pianist has already recorded Schumann’s Carnaval, but I have not yet had the opportunity to hear it. There is an underlying logic to this pairing, as Kenneth Chalmers points out in his liner-notes when he states that ‘an added layer of Beethovenian references in the Schumann makes the solo piece a convincing partner for the concerto’.

As soon as the opening chords of the Beethoven are struck and the magnificent cadenza unfolds, the scene is set for, a compelling and magisterial reading – an epic view. The composer indeed set a precedent with this opening; how different to those quiet, unassuming chords which usher in the Fourth. Beethoven here establishes the template for the openings of the Romantic concertos which were to follow. The first movement is everything it should be: bold, imposing, strong and virile. Both the aristocratic and heroic characters are established in the opening tutti by Daniel Harding and his Berlin players. What impressed me is that the performance is never excessive and there is a notable absence of any grandstanding, which can kill it dead in its tracks. Harding is a sensitive collaborator, who has an innate understanding of the structure and architecture of the work. He gives both soloist and orchestra each their moment in the sun.

In the second movement, Yundi achieves an exquisite diaphanous tone. Phrases are beautifully shaped and dynamics spot-on. Harding remains responsive at all times, and I love the way he coaxes the woodwinds, striking an ideal balance between them and the soloist. The finale enters without a break with Yundi setting an upbeat and buoyant tempo. His wonderful technique enables him to handle the demands that this concerto presents. It all ends in a blaze of glory.

This stands up well to competition in a very crowded field. I would certainly place it on the shelves next to my preferred versions by Pollini/Böhm, Pollini/Abbado, Brendel/Rattle and Brendel/Levine. I shall return to it often.

The Fantasy in C major, Op. 17 was composed in 1836 and published, with revisions, in 1839. It was dedicated to Franz Liszt. The first movement has its origins in the painful separation between Robert and his future wife Clara as a result of the machinations of her father, Friedrich Wieck. The remaining two movements were to be Schumann’s contribution to an appeal for a monument to Beethoven in Bonn.

This ticks all the right boxes. In the first movement Schumann pours out his soul at his separation, even quoting Beethoven’s An die ferne Geliebte (to the distant beloved). Yundi delivers a passionate and sensitively sculpted performance. The wonderful left-hand semiquavers that accompany the opening melody underpin a grand gesture and romantic sweep. There’s great nobility here.

The grandiose march theme of the second movement is judiciously paced, with the obsessive dotted rhythms that follow conveying no signs of monotony. Yundi’s brilliant virtuosic technique enables him to convincingly bring off the treacherous leaping skips in the coda. How many times do we hear caution or strain here, or even misfires - not so with Yundi. The poetic and sublime finale sounds like an extended song without words. This is truly transcendental playing, conveying a sense of otherworldliness.

I can’t deny that I had initial misgivings about the pairing of these two works, but having listened several times I no longer have any such reservations. The piano sound in both items is warm and full. Balance between piano and orchestra in the Beethoven is ideal. For those who admire prodigious pianism, this is a treat not to be missed.

Stephen Greenbank

Masterwork Index: Beethoven

piano concerto 5

|

|

|