|

Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from |

|

|

|

|

|

|

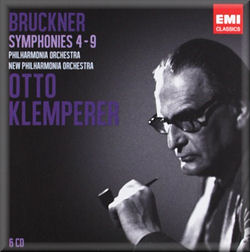

Anton BRUCKNER (1824-1896)

Symphony No. 4 (1886, ed. Nowak) [61:01]

Symphony No. 5 (1878, ed. Nowak) [79:29]

Symphony No. 6 (1881, ed. Haas) [55:50]

Symphony No. 7 (1884, ed. Nowak) [65:11]

Symphony No. 8 (1890, ed. Nowak and Klemperer) [84:19]

Symphony No. 9 (1887-96, ed. Nowak) [65:18]

Philharmonia Orchestra/Otto Klemperer

New Philharmonia Orchestra/Otto Klemperer

rec. 18-26 September 1963 (No. 4), 9-15 March 1967 (No. 5), 6-19 November

1967 (No. 6), 1-5 September 1960 (No. 7), 28-30 October, 10-14 November

1970 (No. 8), 6-21 February 1970 (No. 9), Kingsway Hall, London

EMI CLASSICS 4042962 [6 CDs: 61:01 + 79:29 + 65:11 + 64:49 +

74:30 + 65:18]

At the end of his career, between 1954 and 1971, Otto Klemperer (1885-1973)

made a series of celebrated recordings for EMI with the Philhamonia

and its reconstituted equivalent the New Philharmonia. The repertoire

ranged widely, and EMI is honouring these famous performances by reissuing

them in a series of boxed sets. Thus far these have included Beethoven,

19th century symphonies and overtures from Schubert to Tchaikovsky

and Mozart’s Don Giovanni. Now comes this 6-CD collection

of Bruckner symphonies, from the Fourth through to the unfinished

Ninth.

Throughout his distinguished career Klemperer was associated with

Bruckner, and during the 1920s the association enhanced his reputation.

He made an interesting observation that while he thought Bruckner

the greater composer, he always conducted Mahler more frequently ‘because

like me he was a Jew and moreover he got me my first job’.

These performances from 1963 to 1970 are captured in excellent sound,

and though nearly fifty years has passed since the first of them –

the Fourth – there is no need to be in the least apologetic about

the sound quality. The producers were Walter Legge, Peter Andry, Walter

Jelinek and Suvi Raj Grubb.

By reputation Klemperer has always been associated with slow, even

sluggish tempi, but that is not necessarily fair or even true. For

example, each of his modern recordings of Mahler’s Resurrection

Symphony, live with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and

in the studio with the Philharmonia, fit comfortably on to a single

CD, whereas Sir Simon Rattle’s CBSO recording requires two discs since

the tempi are broader. This is just one example among many, and here

in Bruckner Klemperer’s tempi are never less than appropriate.

Perhaps it is the nature of the phrasing and shaping of the music

that influence the listener’s experience of Klemperer’s Bruckner performances

the most. He sculpts and moulds the music rather less than Eugen Jochum

or Wilhelm Furtwängler, and his shadings of dynamic and phrasing are

less pliable than those of Günter Wand. Not that one approach is right

and the other wrong; there is always more than one way to interpret

a great symphony.

In the Fourth Symphony Klemperer’s live Munich performance with the

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (EMI CDM 5 66866 2 5; recorded 1966;

reissued 1998) has a more spontaneous feel than the present Kingsway

Hall version from three years earlier, though the recorded sound in

the latter seems more secure. Here the famous Scherzo is craggy rather

than virtuoso, while the architecture of the powerful finale has never

been more surely controlled.

The Fifth too is a particularly strong performance, at nearly eighty

minutes taking slightly longer than he did with the Vienna Philharmonic

the following year (Testament UCCN-1059) and a full ten minutes longer

than his first recorded version, made with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw

Orchestra in 1957 (Archiphon WU-091). The approach with the Philharmonia

suits the music admirably. The finale’s reconciliation of chorale

and fugue is uncompromisingly argued, the two aspects held in clear

contrast at the same time as joint purpose. The string sound in the

slow movement is also particularly impressive.

This famous recording of the Sixth Symphony has long been held as

perhaps the top recommendation. Klemperer has a strong long-term view

of the architecture, while the symphonic drama is cogently articulated.

To my mind other performances - for instance Günter Wand on RCA CD

68452 2, or Ferdinand Leitner on Hänssler Classics CD 93.051 - open

the work with a lighter rhythmic touch and therefore more effectively,

whereas Klemperer’s rhythm and phrasing seem somewhat stodgy. However,

as things develop there is no arguing with the strength and vision

of his reading, nor ultimately with the comprehensiveness of the conclusion

to the finale - another aspect of the symphony that is notoriously

hard to bring off.

The Seventh is given a direct and weighty performance, less visionary

perhaps than great interpretations such as those by Eugen Jochum (with

the Berlin Philharmonic, DG CD 459 068-2) or Stanislav Skrowaczewski

(with the Saarland Radio Symphony, Arte Nova CD 777123), but with

its own undeniable strengths and personality. The slow movement for

example is more mobile than some and reaches to a powerful climax

replete with cymbal clash, while the scherzo is emphatic and the finale

makes for a cogent ending to the whole work. The concluding feels

satisfyingly comprehensive.

It is the Eighth Symphony that raises the most doubts among these

performances. It is a typically powerful and craggy performance, lacking

the fluidity that is the hallmark of Günter Wand’s masterly approach,

for example with the North German Radio Symphony Orchestra, RCA/BMG

CD 68047-2. That said, Klemperer always maintains the music’s direction

and symphonic integrity … until the finale, that is. Astonishingly

for someone who knew, loved and understood Bruckner’s music so well,

Klemperer decided to make his own edition making cuts (bars 211-387

and 582-647) amounting to about seven minutes of music. They prove

far from convincing.

In 'Otto Klemperer - his life and times' by Peter Heyworth

(Volume 2, CUP 1996, p353) the conductor gave his explanation: 'In

the last movement of Bruckner's Eighth Symphony I have made

cuts. In this instance it seems to me that the composer was so full

of musical invention that he went too far. Brucknerians will object,

and it is certainly not my intention that these cuts should be considered

as a model for others. I can only take responsibility for my own interpretation.'

On these grounds alone Klemperer’s Eighth can’t be a first recommendation.

However, anyone acquiring this set may well be adding a new version

to an existing collection, so the matter then becomes one of adding

an interesting variety to the possibilities offered by a great symphony.

The Ninth is another great performance; from the first bar the concentration

is extraordinary and compelling, even if less atmospheric than many

interpretations. The first climax is absolutely gripping, and out

of it the tremolando strings and woodwind interjections edge their

way forward, to be relieved by the beauties of the string writing

in a gesängperiod of boldly slow articulation. As such the rich tone

of the cello line makes a deeply compelling impression. This symphony

has a grandeur that is unique even in Bruckner’s output, and Klemperer’s

interpretation brings a special quality to it.

The middle movement scherzo is pounding and dark and very fast, while

the central trio is no less intense. On the other hand the finale

is broadly paced, yet full of sharply defined contrasts, and sometimes

moving towards a slower Adagio pulse than Klemperer chooses elsewhere.

There is an extraordinary world of visionary intensity here, and this

makes the closing bars, with their resolution amid a mood of calm

assurance and acceptance of fate, all the more moving.

This collection is nicely packaged in an easily accessible box, with

each disc in its own card case. Given that the back of these cases

is largely blank save for identifying the symphony contained therein,

it is disappointing that the movement headings aren’t included too.

To find these one has to search in the accompanying booklet, where

all the details are clearly laid out. There are also some excellent

essays by Richard Osborne on ‘Otto Klemperer’ and ‘Klemperer’s Bruckner’,

though surprisingly there are no notes on the music itself. As so

often in collected sets, the music seems to play second fiddle to

the artists as far as the documentation is concerned. This is a misjudgement

and surely EMI should have included the existing notes they had on

file.

Klemperer’s contribution to the legacy of Bruckner recordings is important

and impressive, and as such this set deserves an enthusiastic welcome.

Any collection of the symphonic output of this wonderful composer

- the greatest symphonic composer? - will be enhanced by it. Even

the collector who already possesses this repertoire in alternative

performances will find this set rewarding and stimulating.

Terry Barfoot

see also

review by Christopher Howell

|