|

|

Support us

financially by purchasing this disc from

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

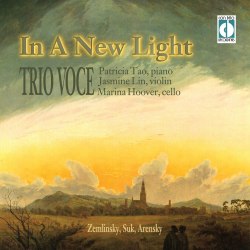

In a New Light

Alexander von ZEMLINSKY (1871-1942)

Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 3 [28:17]

Josef SUK (1874-1935)

Piano Trio in C minor, Op. 2 [17:03]

Anton ARENSKY (1861-1906)

Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor, Op. 32 [33:05]

Trio Voce

rec. 10-12 December 2012, WFMT Studios, Chicago

CON BRIO CBR21344 [78:25]

Trio Voce presents a set of three piano trios from the 1890s, all in minor keys, all imbued with the sort of high-romantic emotional intensity that sets hearts racing. The opening of Alexander von Zemlinsky’s trio in D minor strongly evokes a composer who would come to prominence a decade later: Rachmaninov. In all three works, the piano, violin and cello trade long, dark melodies that bring Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky and Brahms to mind. Speaking of Brahms, the Zemlinsky work was originally scored for clarinet, cello and piano, directly modelled after a Brahms piece for the same instruments. That version is still more common and can be heard on a pretty good Naxos disc featuring the Vienna Philharmonic’s principal clarinetist.

It’s interesting, given all the minor-key emoting going on, that the other two composers distinguish themselves most in the “reprieve” sections. Josef Suk’s trio, a student work written under Dvorak’s tutelage and completed at age 17, stands out because of its lighter slow movement, which - like, say, Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony - is too balletic and bubbly to be a proper slow movement. The violin and cello intertwine in a song-like duet, the cello often sitting on the high end of its range.

Likewise, Anton Arensky, a Russian whose cheerful disposition is evident in his several orchestral suites, can’t help but insert a joy of a scherzo with a waltz trio that throbs with energy and passion. It’s almost like the trio of Schubert’s last symphony put into waltz time. The Arensky work is an elegy, though, and thus has a mournful slow movement and a quiet ending in which the work fades away. An elegy for whom? Although nominally for cellist and friend Karl Davidoff, it’s also in part for Tchaikovsky, a mentor and influence who had died the previous year.

The booklet notes are short but sweet. It’s amusing to learn that Anton Arensky was apparently so deeply unpleasant a person that Rimsky-Korsakov dedicated a diary entry to insulting him. “In his youth Arensky did not escape some influence from me; later the influence came from Tchaikovsky. He will quickly be forgotten.” Funnily, Tchaikovsky is the reason Arensky has not been forgotten. This piano trio, written in Tchaikovsky’s shadow, and a string quartet with just one violin and two cellos, which explicitly mourned Tchaikovsky’s death, are his best-remembered works.

Throughout the recital the Trio Voce play very well, with the requisite high-octane mix of energy, passion and heart-on-sleeve romantic exuberance. They seem to be chameleon-like performers, since their last album, of bleak Soviet stuff by Weinberg and Shostakovich, was also a big success. I’ll be curious to hear where they turn next.

The recorded sound is well-balanced, like you’re in the third or fourth row of a small recital hall. There’s never any congestion; all three players are always audible. In the first track, also audible is a tiny high-pitched hum or throb which cuts in and out sometimes during violin solos. It will only bother you if you have fancy headphones and young ears.

Brian Reinhart

|

|

|