|

|

Support us

financially by purchasing this disc from

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

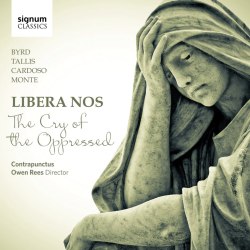

Libera nos - The Cry of the Oppressed

Track listing below review

Contrapunctus (Esther Brazil, Amy Moore, Roya Stuart-Rees, Katie Trethewey

(soprano), Rory McCleery, Matthew Venner (alto), Benedict Hymas, Andrew

McAnerney (tenor), Greg Skidmore, Giles Underwood (bass))/Owen Rees

rec. 26-29 November 2012, Church of St Michael and All Angels, Oxford,

UK. DDD

Texts and translations included

SIGNUM CLASSICS SIGCD338 [69:33]

The title of this disc is an indication of what is to be expected:

motets of a mostly gloomy character. Such pieces are often the most

beautiful, and this disc bears witness to that. The programme is full

of masterpieces by English and Portuguese composers. This combination

of motets from two entirely different traditions may surprise. However,

it is the disc's title which holds the sequence together: they "express

the plight of Catholics in England and of the Portuguese under Spanish

rule in the late 16th and early 17th centuries", as Owen Rees writes

in the booklet.

We should not forget that this is his interpretation of the music.

There can be little doubt that texts from the Bible or non-biblical

sources from long ago can be used - and have beeen used in the course

of history - to express the feelings of individuals or the collective.

However, it is often hard to be sure whether that was the case. If

one looks at the track-list one will see that many titles are quite

common. These texts were set by various composers during the renaissance

and often also in later centuries. Many of them are biblical or liturgical.

This means that the very fact that a composer uses them cannot of

itself be taken as an indication that they express his personal feelings.

It is quite possible that motets by William Byrd, which were sung

during secret Catholic worship in private chapels, were interpreted

by the worshippers as an expression of their personal feelings about

their situation. That doesn't necessarily mean that the composer wrote

those motets with that particular purpose. Owen Rees goes pretty far

out on a limb by suggesting that a passage from the text of Plorans

ploravit could refer to James I and his wife Anne of Denmark:

"Say to the king, and to her that rules: Be humbled, sit down, because

the crown of your glory is come down from your head".

Equally a matter of interpretation, rather than based on firm historical

evidence, is his view that the motets by the Portuguese composers

Pedro de Cristo and Manuel Cardoso are expressions of the feelings

of the Portuguese about their loss of independence and their suffering

under Spanish rule. Rees refers to the 'Sebastianism', the belief

in a national saviour who would restore the country to its former

glory. He sees these feelings "vividly evoked" in Pedro de Cristo's

motet Lachrimans sitivit anima mea. Again, one cannot exclude

that it was meant this way, but it is hard to prove. The connection

between music and the current situation of the composer or his audience

may claim a large amount of plausibility, but that is not the same

as evidence.

Let's turn to the music. Some pieces may be quite familiar: in particular

the pieces by Byrd and Tallis are frequently performed. Performing

them within the concept of this disc lends them a different dimension,

even without the references to politics. It allows the listener to

compare the way various composers have set texts of a comparable content.

Rees' notes point out the devices which the composers used to shed

light on specific passages. One of these devices is the alternation

of polyphony and homophony. The end of Byrd's monumental Infelix

ego which - after a pause - focuses on the phrase "Miserere mei,

Deus" is a striking example. He does the same in the second phrase

from Civitas sancti tui: "Sion deserta facta est": Sion has

become a wilderness. Tallis uses homophony to single out "Parce, Domine"

(Spare, O Lord) in In jejunio et fletu.

'False relations' were part of polyphonic writing in England in the

16th century, and several motets on this disc bear witness to that.

In the music written at the Iberian peninsula this was much rarer.

The Portuguese pieces on this disc are from a much later date than

the English compositions. There are some daring harmonies in Sitivit

anima mea by Manuel Cardoso. Martin Peerson also belongs to a

later generation than Byrd. There is a stronger connection between

text and music and a more direct illustration of the text. Laboravi

in gemitu shows the influence of the contemporary madrigal. The

word "lacrimis" (tears) is vividly depicted by the lively rhythms.

The motet by Philippus de Monte is a bit of an outsider in this programme:

he was neither English nor Portuguese but a late representative of

the Franco-Flemish school and worked for many years at the service

of the Habsburg emperors in Vienna and Prague. His motet Super

flumina Babylonis has been included for a reason. There seems

to be a connection between this motet and Byrd's Quomodo cantabimus.

De Monte sets the verses one to four from Psalm 136 (137), Byrd verses

four to seven. These two motets are found in the same source, and

the presence of De Monte's motet could be the result of his visit

to England in 1554-55 as a member of the chapel of Prince Philip of

Spain. Byrd's motet could be a direct reaction to De Monte's motet.

Both pieces are scored for eight voices, but the composers use this

scoring quite differently. De Monte splits the voices into two groups,

which results in a clearer audibility of the text. This reflects the

tendency towards a closer connection between text and music at the

end of the 16th century. It is also an answer to the wishes of the

Council of Trent that texts should be given more attention in liturgical

music. Byrd, on the other hand, creates a dense polyphonic texture

which makes the text much harder to understand. As a musical structure

his motet is nonethelss quite impressive.

The ensemble Contrapunctus was founded in 2010 and this is their first

disc. They could hardly have made a better debut. The singing is superb:

the voices are beautiful and their blending is perfect, without ever

losing their individual character. One of the strenghts is the excellent

balance within the ensemble: here the sopranos do not dominate, and

the lower end has good presence. There is no hint of a wobble in the

lower voices. When the text is to be clearly understood, the singers

make that happen. Owen Rees is not afraid of some pretty strong dynamic

shading, such as in Cardoso's motet. The programme includes a number

of well-known pieces, but also some neglected jewels. That includes

the reconstruction of Tallis's Libera nos which is mostly performed

instrumentally as only the incipit of the text is known. The

'political' interpretation may be questionable, but the compilation

of pieces with its rather gloomy accent makes this programme attractive.

The texts may not spread happiness but the singing can hardly fail

to please.

Johan van Veen

http://www.musica-dei-donum.org

https://twitter.com/johanvanveen

Track Listing

William BYRD (1540-1623)

Civitas sancti tui [5:02]

Thomas TALLIS (c.1505-1585)

Libera nos [2:08]

Philippus DE MONTE (1521-1603)

Super flumina Babylonis [5:41]

William BYRD

Quomodo cantabimus [8:38]

Manuel CARDOSO (1566-1650)

Sitivit anima mea [4:22]

Martin PEERSON (c.1572-1651)

Laboravi in gemitu meo [5:29]

William BYRD

Miserere mei Deus [3:20]

Pedro DE CRISTO (c.1550-1618)

Lachrimans sitivit anima mea [5:54]

William BYRD

Plorans plorabit [5:07]

Thomas TALLIS

In jejunio et fletu [4:54]

Salvator mundi [2:50]

Pedro DE CRISTO

Inter vestibulum [2:33]

William BYRD

Infelix ego [13:34]

|

|

|