|

Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from |

|

|

|

|

|

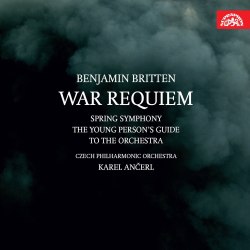

Benjamin BRITTEN (1913-1976)

War Requiem, Op. 66 (1961-62) [79:27]

The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, Op. 34 (1946)* [17:13]

Spring Symphony, Op. 44 (1948-49)** (sung in Czech) [42:55]

Naděžda Kniplová (soprano); Gerald English (tenor); John Cameron (baritone); **Milada Šubrtová (soprano); **Věra Soukupová (alto); **Beno Blachut (tenor)

Prague Philharmonic Choir; Kühn Children’s Chorus

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra/Karel Ančerl

rec. live, 13 January 1966, *3 May 1958; **17 January 1964

Original texts, Czech * and English translations included

SUPRAPHON SU 4135-2 [80:36 + 60:45]

This must be one of the more unexpected Britten centenary issues.

Here we have three previously unpublished live Britten performances,

including the Czech première of War Requiem, all conducted

by the great Karel Ančerl.

Ančerl’s discography attests to his strong advocacy of

twentieth century music. He’s especially renowned for his work

in the Russian and Czech repertoire. However, the booklet note points

out that the music of Britten featured quite often in his programmes.

He first conducted The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra

in 1957. The performance preserved here was given the following year,

quite possibly around the time that he made his commercial recording

of it for Supraphon. The performance of Spring Symphony is

one of a series of three that the conductor gave in Prague at that

time; whether the piece featured in his programmes at other times

I don’t know. The account of War Requiem was, as I mentioned

above, the first performance of the work in Czechoslovakia and one

wonders whether this was a courageous choice of repertoire at that

time. Ančerl gave the work again in Toronto in 1969 with Gerald

English once more as one of his soloists - I wonder how many prior

performances had been given in Canada - and he programmed other pieces

by Britten during his time leading the Toronto Symphony.

Ančerl demonstrates a fine grip on the score. There are some

drawbacks to this recording and it’s as well to mention these

at the outset. A good deal of orchestral detail is dimly heard and,

unfortunately, the chamber orchestra is far too recessed in the sound

picture. Another disappointment is that at times the choir either

doesn’t sing softly enough - at the very start, for instance

- or else is too closely recorded. I rather think it’s more

a matter of dynamics because some quiet passages, such as the ‘Kyrie’

at the end of the first movement or the choral contribution to the

Agnus Dei, are well done. However, as I listened I felt that the essential

spirit of the music was definitely being conveyed and for that

much of the credit must go to the conductor.

So, for example, though the dynamic levels deprive us of much of a

feeling of suspense at the very start - and again at the start of

the Libera me - Ančerl ensures that the ‘Dies Irae’

is dramatic and he generates great power in the ‘Hosannas’

in the Sanctus and Benedictus. His handling of the concluding ‘Let

us sleep now’ ensemble is also impressive. For the most part

the tenor and bass solo sections are done well though I wish Ančerl

could have persuaded Gerald English to be more imaginative in his

solo during ‘Strange meeting’. Overall, however, I find

Ančerl’s interpretation very convincing.

Two Anglophone singers were engaged for this performance. I’m

a little wary of judging because this performance took place less

than four years after the première so the performing tradition

of the work was still being established and the exemplars in the roles

at that time were Pears and Fischer-Dieskau. The other thing that

gives me pause for thought is that there have been so many notable

exponents of these parts since then - Bostridge, Padmore, Keenlyside

and Hampson are just four names that spring readily to mind - that

we are rather spoiled. Nonetheless, for all the virtues of their singing

- including well-focused tone, clarity of diction and pinpoint accuracy

- I do feel that both singers inflect the words with rather less imagination

and feeling than do several singers one has heard. English is particularly

disappointing in his solo in ‘Strange meeting’, which

he takes quickly and with little sense of horror or fear - John Cameron

is much more characterful when he takes over in this setting. Cameron,

too, sometimes is a little lacking in imagination: ‘Be slowly

lifted up’ is sung strongly but I hear no menace. Having said

all that, both soloists offer much that is positive: English’s

singing is consistently clear and incisive and Cameron has a fine,

rounded tone and an excellent sense of line. I just feel that neither

really conveys enough poetry or deep feeling; generally, their approach

is straightforward and direct and not as subtly nuanced as I’ve

heard from a number of soloists in other performances.

Ančerl chose a good soprano. Naděžda Kniplová

(b. 1932) was not an artist I’d encountered before but she makes

a good showing here. She projects the ‘Liber scriptus’

powerfully and accurately. This section and the start of the Sanctus

show that she’s fully up to the work’s histrionic challenges.

Just as impressive as her compelling singing in those passages, however,

is her gentle approach to the Benedictus. She’s suitably intense

in the ‘Lacrymosa’.

The choral contribution is generally good, notwithstanding my reservations

about soft dynamics. The ladies sound a bit matronly in ‘Recordare’

and ideally I’d like more bite in the men’s singing of

the ‘Confutatis’. However, elsewhere the choir does well

- there’s vigour in the first airing of the ‘Quam olim

Abrahae’ fugue and plenty of punch in the ‘Dies irae’.

The boys’ choir is very good.

Overall, there’s much to admire about this performance. The

recording is satisfactory given its age and the fact that it stems

from a live concert rather than studio conditions. I regret that the

instrumental parts are not ideally balanced but at least the choir

is clearly heard. In general I’d say there’s a lack of

front-to-back perspective in the sound.

The live performance of The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra

is a very good one. Lots of orchestral detail can be heard - and not

just because the recording is pretty good for its age - and the playing

of the Czech Philharmonic is excellent. The concluding fugue - taken

as a genuine presto - is very exciting. This is the sole performance

on the set that is not followed by applause.

For Anglophone listeners the prospect of hearing Spring Symphony

sung in a Czech translation may seem a distinctly odd one. However,

the performance itself contains much to enjoy. The Prague Philharmonic

Choir sings well and they - or the engineers - are more attentive

to soft dynamics than was the case in War Requiem, As a result,

Ančerl is able to generate an excellent degree of tension in

the opening of the work. The Kühn Children’s Chorus also

makes a notable contribution, offering pert, bright and breezy singing

in ‘The driving boy’ and singing ‘Sumer is icumen

in’ with pleasing gusto in the finale. The soloists also do

a very good job. The pick of them is Beno Blachut, whose sappy, athletic

tenor is an asset. Věra Soukupová offers some very committed

singing though some may feel her tone is just a bit too full and Central

European for this music. Milada šubrtová’s clear

soprano is heard to good advantage in her duet with Blachut, ’Fair

and fair’, and in the finale. I didn’t find the use of

Czech a great drawback - and, truth to tell, the choir’s words

aren’t that distinct anyway.

Ančerl’s direction of the score is impressive. He’s

clearly committed to the music and he ensures that rhythms are crisply

articulated. I’ve already mentioned the tension he generates

in the Introduction; he does that elsewhere too. The finale is dynamic,

vivid and colourful. There’s much to commend in this performance

and its appearance as part of this set is very welcome.

As I said at the start, this is a somewhat unexpected issue. The recordings

will be primarily of interest to Karel Ančerl’s many admirers,

of which I’m certainly one. I’m very glad to have heard

these discs and it’s good to have confirmation, through these

recordings, that under the guidance of this fine conductor Czech audiences

in the 1960s were able to hear some very faithful and committed performances

of these works. Supraphon have produced the set well. The transfers

are good and despite the fact that these are live recordings from

some fifty years ago sonic limitations don’t preclude enjoyment.

There are useful notes in Czech, English, French and German. The texts

are provided in English and Czech but only as a PDF document which

is included on the second disc.

John Quinn

Britten discography

Masterwork Index: War

Requiem

|

|

|