Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from |

|

|

|

|

|

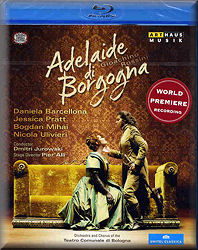

Gioachino ROSSINI (1792-1868)

Adelaide Di Borgogna - Music drama in two acts (1817)

Adelaide, widow of Lotario, King of Italy - Jessica Pratt (soprano);

Ottone, Emperor of Germany - Daniela Barcellona (mezzo); Adalberto,

Berengarioís son - Bogdan Mihai (tenor); Berengario - Nicola Ulivieri

(bass); Eurice, Berengarioís wife - Jeanette Fischer (soprano); Ernesto,

an officer - Clemente Antomnio Daliotti (tenor); Iroldo, former governor

of Canosso - Francesca Pierpaoli Wilde (tenor)

Orchestra and Chorus of the Teatro

Comunale di Bologna/Dimitri Jurowski

rec. live, Teatro Rossini, 2011 Rossini Opera Festival, Pesaro, August

2011

Stage director, Set Lighting and Costume designer: Pier' Alli

Video Director: Tiziano Mancini

Sound Format: PCM Stereo, DD 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio 5.1

Picture Format: 16:9, 1080i full HD

Subtitle Languages: Italian (original language), English, German, French,

Spanish, Japanese, Korean

Bonus: the making of Adelaide di Borgogna

ARTHAUS MUSIK 108 060

[137:00 +17:00 bonus]

As I noted in respect of Arthaus Musicís Blu-Ray issue of Rossiniís

first composition, Demetrio e Polibio from Pesaro the words

World Premiere Recording should only be used when accurate.

In that case the most common known recording dated back to 1992. Wrongly

used again here the excuse is less forgivable. Adelaide Di Borgogna

was performed and recorded, under the aegis of Opera Rara at the Edinburgh

Festival in 2005, the CDs appearing a year later (review).

Accuracy demands that where appropriate the word Video be added to

the advertising hype at Arthaus Musik.

Accuracy also demands some background in respect of the composition

of Adelaide Di Borgogna. Richard Osborne gives the work short

space and little explanation as to its composition in his otherwise

valuable book (The Belcanto Operas, Methuen, 1994 p.80),

nor does he explain why it did not open the Carnival Season at the

Teatro Argentina as contracted. The booklet note with this issue,

whilst giving some historical background in respect of Rossini in

Rome, and his relationship with the impresario, seems to mix up La

Cenerentola with the delay in the premiere of the new opera and

which meant a loss of money to the impresario (p.7).

The success of Rossiniís Tancredi, premiered in Veniceís

on 6 February 1813, firmly established the young manís reputation

as being amongst the leading young Italian opera composers of his

day. He quickly consolidated that position with the sparkling LíItaliana

in Algeri also premiered in Venice on 22 May the same year. Whilst

Milan was less impressed with Il Turco in Italia (14 August

1814) other Italian cities took it up with enthusiasm. These three

works put Rossini in a pre-eminent position among his competitors

causing the formidable impresario of the Royal Theatres of Naples,

Domenico Barbaja, to offer him the musical directorship of the theatres.

Under the terms of his contract, Rossini was to provide two operas

each year for Naples whilst being permitted to compose occasional

operas for other cities. Rossini spent eight years in Naples composing

nine of his opera serie which contain some of his greatest

music. In the first two years of his contract he also composed no

fewer than five operas for other cities, including four for Rome.

These include Il Barbiere di Siviglia premiered on 20 February

1816 Ė which has become the composerís most popular. His second most

popular opera, La Cenerentola, was also premiered in Rome

in January 1817 after which he squeezed in La Gazza Ladra

for Milan in May.

Rossiniís popularity in Rome contributed to his accepting a further

commission for that city even as he was rehearsing Armida

for the San Carlo in Naples in November. Barbaja had demanded a spectacular

from the composer to launch the refurbished San Carlo after a disastrous

fire the year before. With Rinaldo and Armida scheduled

to descend on a cloud, and other magical effects, rehearsals were

demanding of his time. Despite that, Rossini signed another Rome contract

to open the carnival season at the Teatro Argentina on 26 December

1817.

Some have suggested that the pressure of time for the new Rome opera

left the composer over-stretched and the result was too many corners

being cut. The chosen subject of Adelaide Di Borgogna was

to be Rossiniís first opera seria for Rome. It was to be his twenty-fifth

opera. He pillaged the overture from his first staged work, La

Cambiale di Matrimonio, premiered in 1810. There are other recognisable

self-plagiarisms as well as instances where he used the music in later

works. More importantly, for this opera seria Rossini did not utilise

the more complex skills he had acquired at the San Carlo, aided by

its professional orchestra. Instead he reverted to the earlier form

of secco recitative and aria. It was not unlike Mozart going back

to that formal and somewhat static genre for his La Clemenza di

Tito after his three great da Ponte works had seemed to take

opera composition in an altogether different and more entertaining

direction. In Mozartís case it was force of circumstances. What made

Rossini revert is not known. As the autograph does not survive we

do not know to what extent Rossini farmed out the recitatives, or

any of the other music, under the pressure of time. Adelaide Di

Borgogna was not a success in Rome and although it was seen in

other parts of Italy it had disappeared after around 1825. In the

essay accompanying the Opera Rara issue, Dr Jeremy Commons examines

these issues, and whilst accepting some of the arguments about weak

passages, argues strongly in favour of the work.

Schmidtís libretto is set in 10th century Italy. It tells

the story of Adelaide whose husband has been killed by Berengario.

She can be returned to the throne if she marries Adalberto his son.

The German Emperor, Ottone, a trousers role, comes to her aid and,

after his defeat of Berengario, Adelaide and her saviour end in love

and triumph. This production updates the time to nearer the unification

of Italy in 1861, one hundred and fifty years before this performance.

Perhaps the production was intended as a celebration of the event,

albeit being rescued by a German, and having lived under Austrian

occupation for so long it is hardly likely. The army costumes in particular

are indeterminate eighteenth or nineteenth century. There are few

stage props with the whole illustrated by projections, as is the directorís

speciality. Some might be deemed appropriate and relevant; others

less so. The positive view is that they are, in my view, preferable

to the treatment of Sigismondo and MosŤ in Egitto

at Pesaro in 2010 (review)

and 2011 (review)

respectively, albeit he mars his creativity with stupid fighting with

umbrellas (CH.25) and a surfeit of shimmering water. The work does

refer to Como, and it does rain in that area more often than in Pesaro,

but the umbrella scene in particular is an aberration of taste and

an insult to the audience. Elsewhere, the backdrops and projections

sometimes create an elegant atmosphere as in the Church Scene (CH.16).

Apart from the tedium of constant secco recitatives, some items of

the music, particularly the duets, have plenty of Rossinian brio and

thrust, or at least as far as the variable tempi of the conductor

allows. They show the masterís hand whilst having provision for vocal

display and dramatic cohesion. These occasions are amply utilised

by an outstanding quartet of main soloists. In the eponymous role,

the young Australian coloratura soprano, Jessica Pratt, who I admired

in the British premiere of Armida at Garsington in 2010,

(review)

is very good; a considerable career is well under way in this repertoire.

Her coloratura is exact and the top of the voice gleams. I was a little

uncertain at one point if her tone needed more body (CH.14) and was

immediately bowled over by her singing in the following duet with

Ottone (CH.15). It is a tour de force and is justifiably

applauded with enthusiasm.

Any soprano duet with the formidable mezzo Daniela Barcellona in any

Rossini trouser role is going to get applause. Barcellona is the Rossini

mezzo de nos jours. There has been nobody of her singing

and acting skill in these roles and this repertoire since the formidable

Marilyn Horne hung up her vocal chords. It was no mistake on Rossiniís

part that in the act two finale the mezzo Ottone gets the best bits

(CH.28). In this performance Daniela Barcellona is formidable at this

point whilst Jessica Pratt gives her considerable all in the preceding

near ten minute duet with her mezzo colleague (CH.27).

If Jessica Prat is admirable in coloratura so too is the tenor Bogdan

Mihai as Aldalberto. A little stiff in his acting, his flexible pleasant

tone and formidable technique are heard to good effect, particularly

in duets with his father (CH.16), Ottone (CH.9) and Adelaide (CHs.

19-21). His father, Berengario, is well sung and acted by the bass

Nicola Ulivieri whose sonorous, steady and characterful singing is

a strength (CH.12), and like that of Bogdan Mihai, is not equalled

on the Opera Rara recording. Add these two to the principal ladies

and there is the making of a near ideal quartet for Semiramide

when Pesaro get around to it. Also worthy of mention is the ever-reliable

Jeanette Fischer in the comprimario role of Eurice, Berengarioís wife.

Whilst the chorus of the Teatro Comunale di Bologna is outstanding

I fear that conductor, Dimitri Jurowski, does not exhibit much feel

for the Rossini idiom. It is a pity that Alberto Zedda, co-author

Ė with Gabriele Gravagna - of the Critical Edition used, is not on

the rostrum rather than wasting his time in the bonus about the making

of the film and the production. The picture quality is excellent as

are the video choices of Tiziano Mancini.

Robert J Farr

|