|

|

Support us

financially by purchasing this disc from

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

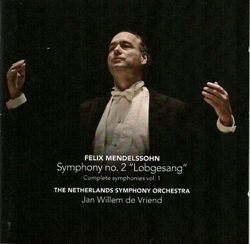

Felix MENDELSSOHN (1809-1847)

Symphony No 2, Lobgesang, Op. 52 (1840)

Judith van Wanroij (soprano); Machteld Baumans (soprano); Patrick Henckens

(tenor)

Consensus Vocalis; The Netherlands Symphony Orchestra/Jan Willem de

Vriend

rec. 19-20 December 2011, 5, 7 July 2012, Muziekcentrum, Enschede, Holland.

DSD

German texts included

CHALLENGE CLASSICS  CC72543 CC72543

[62:36]

This is announced as the first volume in a projected Mendelssohn symphony

cycle by Jan Willem de Vriend and The Netherlands Symphony Orchestra.

De Vriend became chief conductor of the orchestra in 2006. Prior to that

he had made his name as a specialist in period performance, mainly of

pre-Classical music, with Combattimento Consort Amsterdam. I believe his

work with that ensemble continues. My previous encounter with his work

on disc was in a performance of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio with

Combattimento Consort; I enjoyed that very much (review).

De Vriend and his orchestra have already embarked together on a Beethoven

symphony cycle. Several volumes have been reviewed by some of my colleagues,

who have had mixed views about them with Dominy Clements particularly

enthusiastic (review

review

review

review).

I imagine that prior to De Vriend’s arrival The Netherlands Symphony Orchestra

was a conventional modern symphony orchestra but it seems that under his

leadership the orchestra has embraced period practices in the performance

of Classical repertoire. It’s not entirely clear to me from the slightly

ambiguous booklet information how far this process has gone. In the conductor’s

biography we’re told that “by substituting period instruments in the brass

section, [the orchestra] has developed its own distinctive sound in the

18th and 19th century repertoire.” Elsewhere in

the booklet, however, there’s a reference to the orchestra’s “use of period

instruments in the Classical repertoire.” I’m unclear, therefore, whether

period wind and string instruments are employed or whether the players

in these sections content themselves with adopting period techniques on

modern instruments – there’s a singular absence of string vibrato, for

example. Greater clarity on these matters would be welcome, especially

if the musicians are going to the trouble of trying to recreate a period

style. It can’t be the easiest thing for orchestral musicians to chop

and change between period and modern performance practices.

What I can say for certain is that this performance is characterised by

a lean, muscular style across all sections of the orchestra. The orchestral

timbres are light and clear though the ensemble is capable of sufficient

weight where necessary. The lightness extends to the choral contributions

also, though the choir produces adequate volume when required. Again,

there’s no real detail about the size of the choir though I counted just

23 singers in the photograph that’s included in the booklet. It would

appear that Consensus Vocalis, a semi-professional ensemble, specialises

in pre-Classical music.

Mendelssohn entitled his Second Symphony Eine Symphonie-Kantate nach

Worten der Heiligen Schrift. It was commissioned to mark the 400th

anniversary of Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press and was first

performed in Leipzig. The rather poorly written – or translated – booklet

notes tell us that the work “faded into obscurity” and then, a moment

later, that it “has been a great success and has been counted among Mendelssohn’s

best compositions.” Well, which is it? Neglected or highly successful?

The truth probably lies somewhere between the two extremes. One problem

with is that it is neither fish nor fowl. The vocal part of the work is

substantial but, as I recall from having sung in it, you do have to wait

quite a while for the singers to join in the proceedings – or so it seems.

In fact, the three purely orchestral movements play for some 24 minutes

in this performance, which is far shorter than the equivalent movements

in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Unfortunately, in these movements Mendelssohn’s

material and his development of it isn’t nearly as interesting as Beethoven’s.

Nor, indeed, are these movements as involving as are, for example, his

Third or Fourth symphonies. The second and third movements are rather

inconsequential, I fear. That said, Jan Willem de Vriend and his players

make a jolly good case for all this music; the consistently nimble touch

helps greatly. The playing is lithe and athletic in the first movement,

which is, by some distance, the longest of the three, and the brass playing

is punchy without being over heavy. The strings and wind display lightness

and grace in the second and third movements.

The extended choral finale is well done and I applaud Challenge Classics

for providing no fewer than 18 separate tracks. The soloists do well.

It’s not made clear which soprano is singing which part but I presume

that Judith van Wanroij is Soprano I and does most of the singing; it

sounds that way. The two ladies duet effectively in ‘Ich harrete des Herrn’

(track 10) and the soprano in ‘Lobe des Herrn, meine Seele’ (track 6),

who I take to be Miss van Wanroij, makes a good showing though her vibrato

causes her to spread her top notes slightly. Patrick Henckens is an attractive-sounding

tenor and he strikes the right dramatic note in the recitative-like solo,

‘Stricke des Todes hatten uns umfangen’ (tracks 11-13). The choral singing

is crisp and clear; though the body of singers sounds to be chamber-sized

this sound is in keeping with the overall style of the performance. I

didn’t feel that the choir, as recorded, were under-resourced. The choir

is incisive in such passages as ‘Ihr Völker’ (track 19) and the unaccompanied

chorale, ‘Nun danket alle Gott’ (track 16) is very well sung. Incidentally,

this same choir was involved in de Vriend’s recording of the Beethoven

Ninth (review).

As for the orchestra, the positive qualities noted in the three purely

instrumental movements persist throughout the remainder of the work. Jan

Willem de Vriend paces the various sections of the finale shrewdly. I

particularly appreciate the energy he brings to the music, even when the

tempo is not fast; there is no stuffiness or sentimentality about this.

This symphony may not consistently display Mendelssohn at his best but

this performance is a successful launch for de Vriend’s cycle.

The recorded sound is very good – I listened to this disc

in CD format rather than SACD. The booklet contents, whilst adequate,

could be improved and it’s very disappointing that no translations of

the German text are provided.

John Quinn

|