|

|

|

Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from: |

|

|

|

|

|

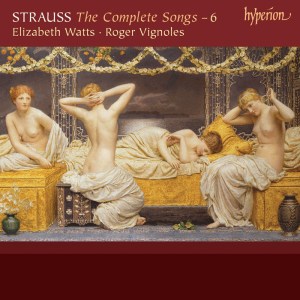

Richard STRAUSS

(1864-1949)

The Complete Songs - Volume 6

Einerlei, Op.69/3 [2.50]

Der Stern, Op.69/1 [2.13]

Waldesfahrt, Op.69/4 [3.38]

Schlechtes Wetter, Op.69/3 [2.36]

Rote Rosen (1883) [2.27]

Die erwachte Rose (1880) [3.29]

Begegnung (1880) [2.09]

Wir beide woollen springen (1896) [1.14]

Das Bächlein, Op.88/1 [2.32]

Blick vom oberen Belvedere, Op.88/2 [4.33]

Krämerspiegel, Op.66 [32.18]

Wer hat’s getan? (1885) [3.41]

Malven (1948) [3.19]

Elizabeth Watts (soprano), Roger Vignoles (piano)

Elizabeth Watts (soprano), Roger Vignoles (piano)

rec. All Saints Church, East Finchley, London, 16-18 January 2012

HYPERION CDA67844 [67.00]

HYPERION CDA67844 [67.00]

|

|

|

“It is easy to be rude on the Continent,” wrote

the Hungarian George Mikes, when exiled in England in 1946.

“You just shout and call people names of a zoological

character.” This observation was certainly true in the

case of Richard Strauss when he wrote his song cycle Krämerspiegel

which lies at the centre of this disc. He was perhaps helped

by the fact that the music publishers at whose heads the insults

were hurled all seemed to have “names of a zoological

character.” He wrote the cycle for the publishing firm

of Bote and Bock, who had insisted on his fulfilment of a contract

to write for them despite the fact that they were at loggerheads

over the issue of composers’ royalties. Strauss took full

advantage of the fact that Bock in German means “goat”.

He also had a pop at a good many other publishing firms for

good measure, and the booklet tells us that Breitkopf actually

insisted on banning for decades any publication of the words

in which he was punningly called a “flathead”. Not

altogether surprisingly, Bote and Bock also declined to publish

the cycle in which they were so viciously attacked.

In fact the set of short songs is rather more just than a series

of diatribes in which music publishers are compared unfavourably

with animals. There are quotations from lots of Strauss’s

own works in the manner of Ein Heldenleben¸ and

even more extraordinarily a first appearance of the beautiful

theme which Strauss was later to employ in the moonlit interlude

which precedes the last scene of Capriccio. Having said

that, the satirical verses are most certainly not masterpieces,

and many of the insults nowadays seem puerile if not incomprehensible.

The Germans seem to have a weakness for puns (as did the Victorians),

and there are plenty of them here. The charming Elizabeth Watts

delivers the insults with a degree of charm which quite defuses

the vitriol in the words, and Roger Vignoles is left to make

up the satirical weight with some dashing delivery of the lengthy

piano preludes, postludes and interludes. It probably needs

a male voice to get some of the crudities in the words across

with full venom, although when one listens to the over-the-top

vituperation of Peter Schreier (on a CD no longer available)

one may welcome the restraint that Elizabeth Watts demonstrates

here.

It must be observed however that in his campaigns on behalf

of composer’s copyright Strauss betrayed no more sensitivity

to political niceties than he did in his brief and disastrous

flirtations with the Nazis after 1933. He quickly founds his

links with the Party severed after his insistence on retaining

the Jew Stefan Zweig as his librettist for Die schweigsame

Frau, but not before he had committed the folly of dedicating

his song Das Bächlein with its final longing refrain

“mein Führer!” to Goebbels. When the song was

published after his death as part of the Op.88 set, the dedication

was discreetly omitted. It is coupled here with its companion

from the same set Blick von oberen Belvedere, an evocation

of the eighteenth century which Strauss treats in a decidedly

un-classical manner.

The disc opens with four songs from the Op.69 set written over

twenty years earlier, and these constitute the most substantial

music in this volume. Combining poems by the Prussian aristocrat

Ludwig Achim von Arnim (1781-1831) with those by the aesthetic

Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) might seem like an odd juxtaposition,

but in the event the two very different authors set each other

off admirably. Roger Vignoles in his booklet note suggests that

Waldesfahrt has suffered by comparison with Schumann’s

setting of the same poem as Mein Wagen rollet langsam,

but Strauss responds with far greater immediacy to Heine’s

words and Watts brings the song to real life.

The Op.69 songs are followed by three pieces of Strauss juvenilia

dating from his teenage years. They are decidedly in the style

of Schumann or Mendelssohn, coming as they do from the period

when Strauss still abominated Wagner and all his works. His

father Franz Strauss had played horn in the orchestra for the

first performance of Tristan in the year after his son’s

birth, and had hated every second of it. They give very little

real indication of what was to come. These pieces were not published

until 1959, when they were first performed by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf.

The style of Watts here - and in other places, too - strongly

suggests the very individual style of Schwarzkopf herself.

There are two other fairly early songs included here which were

not published during Strauss’s lifetime. Wir beide

wollen springen was finally published in 1964, and Wer

hat’s getan? ten years later. It is not clear why

Strauss himself did not include them in one or another of his

collections, but neither deserves total neglect and Watts and

Vignoles make a good case for both of them.

Which brings us to Malven, the last song on this disc

and presumably the last song in Hyperion’s six-volume

collection of the complete Strauss songs with piano. This song

was the very last piece that Strauss wrote, and he sent the

score as a personal gift to the soprano Maria Jeritza with a

request that she should send him a copy - presumably with the

intention of orchestrating it. She never did so, and indeed

never performed the song either; it was not given until 1985

when the manuscript was sold following Jeritza’s death.

This rather sad story of neglect, and the fact that the work

was Strauss’s last work, has led to a good deal of special

pleading on behalf of the song, which has been compared with

the Four last songs written the previous year. It is

true that the song has echoes of that magnificent collection,

especially in the wide-ranging vocal line; and if Strauss had

managed to orchestrate it, the somewhat bare piano part might

have been enriched by increased richness of colour. As it stands,

not even Jessye Norman’s passionate advocacy (on her Philips

collection) can convince me that it is a masterpiece on the

same level as Beim Schlafengehen, to which Roger Vignoles

compares it in his booklet note. Elizabeth Watts does not try

to sell it as hard as Jessye Norman did, which leaves the song

to stand on its own merits; and she is advantageously slower

than Soile Isokoski on Ondine. All the same it makes a rather

sad little postlude to Strauss’s superlative output of

songs.

At the time I was reviewing this CD, Radio 3 undertook a comparative

review of all recordings of Strauss’s songs with piano

as one of their valuable Building a library series. They

came up with a first recommendation for the six-CD set made

by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau with Gerald Moore in 1972, which

included first recordings of a good many of the individual songs

- although excluding the unperformed and unpublished Malven.

The late and lamented Fischer-Dieskau was a very great artist;

but the new Hyperion edition with Roger Vignoles has several

advantages over his ground-breaking survey. In the first place,

they are able to include songs excluded from the Fischer-Dieskau

set; and secondly, they are able to give many of the songs in

the soprano register which Strauss clearly had in mind. In this

context Elizabeth Watts’s recital under consideration

here, although it might be regarded as a collection of various

odds and ends left over from previous volumes, makes for a very

satisfying conclusion to the Hyperion edition. She rescues Krämerspiegel

from the status of a piece of unworthy vituperation; she gives

Malven proper consideration, although without convincing

me that it is a masterpiece; and altogether she gives the music

some of the best performances it is ever likely to get. Earlier

in this review I compared her voice with that of Schwarzkopf;

there could be little higher compliment.

Roger Vignoles is a superb accompanist; and the balance between

voice and piano is just about perfect in a nicely resonant acoustic.

For a real surprise, listen to the postlude to Von Händlern

wird die Kunst bedroht from Krämerspiegel; apart

from the anticipation of the Capriccio theme, we also

get a subtle reference to the same phrase from Tod und Verklärung

with which Strauss brought his Four last songs to a conclusion.

The phrase may be the same, but the result is quite different

although equally effective. That’s mastery for you.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

Reviews of other releases in this series

Volume

1 ~~ Volume

2 ~~ Volume

3 ~~ Volume

4

Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from: |

|

|

|

|

|

|