|

|

|

Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from: |

|

|

|

|

|

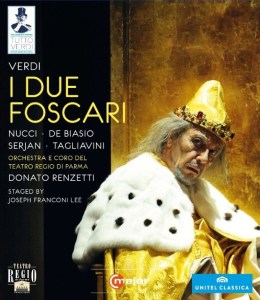

Giuseppe VERDI (1813-1901)

I Due Foscari - Tragic Opera in three acts

(1844)

Francesco Foscari, Ageing Doge of Venice, - Leo Nucci (baritone);

Jacopo Foscari, his son - Roberto De Biasio (tenor); Lucrezia Contarini,

Jacopo’s wife - Tatiana Serjan (soprano); Loredano, an enemy

of the Foscari - Roberto Tagliavini (bass); Barbarigo, friend of

Lorendano - Gregory Bonfatti (tenor); Pisana, Marcella Polidori

(soprano); Doge's Servant - Alessandro Bianchini (bass)

Francesco Foscari, Ageing Doge of Venice, - Leo Nucci (baritone);

Jacopo Foscari, his son - Roberto De Biasio (tenor); Lucrezia Contarini,

Jacopo’s wife - Tatiana Serjan (soprano); Loredano, an enemy

of the Foscari - Roberto Tagliavini (bass); Barbarigo, friend of

Lorendano - Gregory Bonfatti (tenor); Pisana, Marcella Polidori

(soprano); Doge's Servant - Alessandro Bianchini (bass)

Orchestra and Chorus of the Teatro Regio, Parma, Italy/Donato Renzetti

Director: Joseph Franconi Lee; Set and costumes by William Orlandi

Video Director: Tiziano Mancini

rec. Teatro Regio, Parma Festival, 11 October 2009

Video format: 1080i. Aspect: 16:9. Sound Format: DTS-HD MA 5.01

Subtitles: Italian (original language), English, German, French,

Spanish, Chinese, Korean, Japanese

Booklet essay in English, German and French

C MAJOR

C MAJOR  721104 [115:00 + 10:00]

721104 [115:00 + 10:00]

|

|

|

I due Foscari was Verdi's sixth opera and is numbered

likewise in this series called Tutto Verdi which will

encompass all twenty-six, plus his Requiem, from the

Parma Verdi Festival. They are issued to celebrate the bicentenary

of composer’s birth. As I noted in my review of number

three, Nabucco, this statement does beg a question as

there are twenty-eight different titles in the Verdi canon Two,

Jérusalem (1847) was a re-write of his fourth

opera, I Lombardi (1843) to a French libretto for the

composer’s debut at the Paris Opéra, and Aroldo

(1857) was a re-write of Stiffelio (1850) to get away

from the portrayal of a married Protestant Minister that offended

some audience sensibilities. I suspect that these two re-writes

will not feature in Tutto Verdi, I also expect that the

two other operas that Verdi wrote to French libretti for Paris,

Les Vêpres Siciliennes (1855) and Don Carlos

(1867) will be recorded in their Italian translations. These

statements are not meant as criticism as the project is particularly

welcome because of the venues chosen. The project will make

available video recordings of Verdi operas not hitherto available.

The first of these, Un Giorno di Regno, Verdi’s

second opera, is already available and will be reviewed shortly,

his eighth,Alzira, is promised.

Verdi had considered an opera based on Venice for his fifth

work. This was scheduled for his debut at the Teatro La Fenice,

premiere opera house in that city, in the Winter Season of 1844.

However, Venice had the reputation of a festival city, its darker

side carefully concealed. Consequently, Verdi was warned off

and instead set Ernani.For his Rome debut later

that year, and after the censors had considered his first choice

as being subversive, his thoughts returned to an opera based

on Venice and in particular on Lord Byron's play The Two

Foscari. With his innate feel for the theatre he recognised

that the play did not have the theatrical grandeur needed for

an opera and instructed his librettist, Piave, to find content

to add a splash.

Set in Venice around 1457, the story concerns the aged Doge,

Francesco Foscari, who has made enemies in the all-powerful

Council of Ten. His son Jacopo, has been charged and tortured

on false accusation and sent to exile away from his wife and

children. His wife pleads with his father, as Doge, to exercise

clemency and allow his son to return to Venice. Francesco cannot

usurp his judicial duty and his son is sentenced to further

exile. As Loredano, an implacable enemy of the Foscari gloats,

Francesco, as father, meets his son in prison. Jacopo is summoned

to be told he is to be exiled again, with his wife and children

forbidden to accompany him.

In the final act, preceded by a regatta and Venetian Festival,

Jacopo is led to a boat for exile. Back in the Doge’s

Palace his father reflects that the last of his three sons has

been taken from him. A letter revealing Jacopo’s innocence

arrives too late as the young man has died of grief. Bereft,

Francesco then faces the ultimate insult of being forced to

abdicate his position and Lucrezia returns to find him stripped

of his crown and robes. He dies of grief.

This production by Joseph Franconi Lee was seen in Bilbao in

November preceding this recording. William Orlandi’s set

and costumes are traditional and in period. There are no regietheater

idiotics or idiosyncrasies. His set of a wide stepped front,

somewhat in the Pierre Luigi Pizzi style, is backed by sliding

panels which open and close to reveal quick scene-changes. In

act three they also reveal a very colourful backdrop for the

dancers at the Festival as Jacopo is sent to his second exile.

The Teatro Regio in Parma is beautiful in itself and of modest

size. The singers do not have to force, particularly when accompanied

by a maestro of such experience and sympathy as Donato Renzetti.

The title role is sung by Leo Nucci, at the time just past his

mid-sixties. Compared with his performance as Nabucco the same

year he seems to find the role less stressful and although he

scoops occasionally he exhibits little of the vocal spread and

unsteadiness I found in that performance. I regret that despite

his long professional life in the top league of Verdi baritones,

he could not refrain from breaking role and acknowledging the

applause after Francesco’s aria near the end of the opera

as the Doge, faces the reality of his position (CH.35). It is

a serious blot on the drama and to a degree unforgivable in

a professional of his standing who had just given a memorable

interpretation. I gather that Nucci did not sing all the scheduled

performances with the young Italian Claudio Sgura proving a

very able substitute.

Roberto De Biasio sang the role of Jacopo Foscari. I recall

admiring his performance as Edgardo in a recording of Lucia

di Lammermoor from the Donizetti Festival at Bergamo in

October 2006 (see review).

I noted that he showed a voice of much promise with a pleasing

clear timbre and making effort at expression as well as singing

mezza and sotto voce when appropriate. These attributes

are evidenced in his interpretation here. I was, however, disappointed

that his phrasing still lacks that vital element of elegance

that raises the merely average singer to the good. He has plenty

of promise and could gainfully learn from Carlo Bergonzi in

this respect.

As Lucrezia, the Russian soprano Tatiana Serjan sang particularly

well and acted with conviction in both body and voice. Her voice

is even, pure, and able to exhibit a wide variety of modulation

and colour. As the implacable Loredano, Roberto Tagliavini sang

with sonority and admirable steadiness, also characterising

well.

The only serious rival on video is that from La Scala in 1988

conducted by Muti (Opus Arte OA LS 3007 D). Renato Bruson acts

superbly, but is not always steady. In the larger theatre neither

the soprano nor the tenor in that issue comes over with any

distinction. On CD, the Philips recording with Carreras as Jacopo,

Cappuccilli as Doge, Katia Ricciarelli as Lucrezia and Sam Remy

as Loredano stands alone in terms of quality (Philips 422 426-2).

Robert J Farr

see also review by Simon

Thompson of DVD release

|

Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|