|

|

|

Support us financially by purchasing this disc from:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

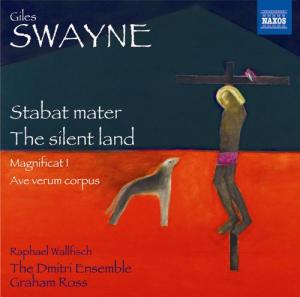

Giles SWAYNE (b. 1946)

Magnificat I (1982) [4.18]

The silent land (1997) [22.58] (2)

Ave verum corpus (2003) [3.08]

Stabat mater (2004) [36.18]

African traditional

O Lulum [1.37] (1)

The La Jola people, Senegal (1)

The La Jola people, Senegal (1)

Raphael Wallfisch (cello) (2)

The Dimitri Ensemble/Graham Ross

rec. All Hallows Church, Gospel Oak, London, 7-9 April 2010, except

for O Lulum. Senegal, 1982

Texts included

NAXOS 8.572595 [68.18]

NAXOS 8.572595 [68.18]

|

|

|

There’s something of a Clare College vein running through this

disc. Giles Swayne, a Cambridge graduate himself, has been teaching

composition at the university since 2003 and has been composer-in-residence

at Clare since 2008. Though Timothy Brown, the college’s Director of

Music between 1979 and 2010, isn’t involved with this disc per

se, Swayne credits Brown with “luring” him back to

Cambridge. Brown directed the first performance of The silent land

and Ave verum corpus was composed for him and the Clare choir. Then

we have Graham Ross, the conductor on this disc and Brown’s successor

at Clare College; he was once a student of Swayne’s at Clare. To

complete the Clare picture the producer, engineer and editor of this disc is

none other than John Rutter. I mention all this not to give the impression

of some cosy club but rather to suggest that here we have evidence of

several experienced musicians collaborating on the choral music of an

important composer and friend.

All but one of these Swayne pieces are receiving their first

recordings. The exception is his 1982 Magnificat which, by coincidence, I

first heard in a recording conducted by John Rutter. It’s based on a

traditional Senegalese song which Swayne encountered and recorded while

undertaking field research in Senegal. I’ve heard the Magnificat

several times, both on disc and in performance, but I’ve never heard

the song on which it’s based. Here, very imaginatively, the recording

that Swayne made over thirty years ago precedes the Magnificat and I found

that tremendously helpful. Swayne’s piece contains complex, robust and

exuberant choral writing which is delivered superbly here; I’ve never

enjoyed the piece so much.

The silent land is described by the composer as the outcome

of his desire to write “a Requiem which omitted God, punishment and

reward, and concentrated on the acceptance of human loss.” For his

text Swayne assembled words by Christina Rossetti, Robert Louis Stephenson

and Dylan Thomas as well as from the Requiem Mass. The work is scored for

solo cello and, like Tallis’s Spem in Alium, eight five-part

choirs, with each choir including a soloist so that there’s in effect

an SATB semi-chorus. The cello represents the individual soul, the

semi-chorus the grieving family and the main choirs the “wider

community”.

The piece is not for the faint-hearted. From start to finish the

music is extremely intense and impassioned and I didn’t find listening

to it a comfortable experience - I’m sure Swayne didn’t intend

it to be. It’s music that confronts the listener. At times, especially

during roughly the first half of the piece, the choral textures are teeming

and as the volume increases the cello is almost overwhelmed, quite possibly

by design. From about 12:30 onwards the singers sing over and over again the

words “Requiescant in pace” against which the cello has

impassioned, pretty unceasing music. I don’t know whether this is the

intention but I received the impression that the soul, as represented by the

cello, is in its death throes, struggling - and perhaps raging - against the

onset of death. The piece is a tour de force for all concerned and it

receives a performance of blistering intensity.

All that said, my subjective response to The silent land is,

at best, lukewarm. Partly this is a matter of personal taste. I found it all

pretty unrelenting and even, at times, aggressive. Furthermore - and I

acknowledge readily that we all have individual responses to works of art -

it seems to me that there is a gentle, consoling aspect to the Rossetti

words in particular and Swayne’s music strikes me as completely at

odds with this side of the words. The music eventually attains quietness of

a sort in the last three minutes or so but then the very last time that the

choir sings “Requiescant in pace” it’s in a manner that

sounds more like an angry demand than a plea. The other reaction I have to

the piece is that it seems too long. I don’t feel much would have been

lost if the section from 12:30 to the end had been half the length. This is

not for me, I’m afraid, and I can’t see myself returning to this

piece.

If I say that the music of the Stabat Mater is more

“traditional” I don’t mean that in any derogatory fashion.

Swayne himself says that he felt it right to use “simple musical

language” on this occasion and the result is a piece that I found much

more approachable than The silent land yet it sacrifices nothing in

terms of eloquence or intensity. In contemplating setting the medieval

Christian text Swayne says that he was conscious of the Israeli-Palestinian

conflict and that “the events it [the Stabat Mater] relates are being

repeated today, a stone’s throw from the place where Jesus is said to

have been crucified.” As he says when people perish in conflict,

“it is always the women who are left behind.” So in this setting

for unaccompanied SATB soloists and choir Swayne juxtaposes the Latin text

of the Stabat Mater with Hebrew and Aramaic texts. I think this works

extremely well and Swayne has produced a work that is nothing if not

thought-provoking.

Though he’s used simpler musical language as compared to

The silent land I doubt the Stabat Master is any less demanding to

sing. The music is often searingly intense and the performance it receives

here is similarly intense. The singing has tremendous conviction and the

four soloists sing their roles ardently. I found it challenging to hear but

rewarding and moving. Unlike The silent land I felt that the piece

sustains its length - perhaps it helps that it’s divided into thirteen

separate sections, each helpfully tracked separately by Naxos. The

performance of this testing piece generates genuine and consistent tension

and this is a piece to which I expect to return.

It’s always a little difficult to judge when one is listening

to unfamiliar music, particularly the music of our own time, but it seems to

me that Graham Ross and The Dimitri Ensemble deliver tremendous performances

of these challenging pieces. The music-making burns with conviction and I

would imagine that Giles Swayne is delighted with the results. The recorded

sound has terrific presence and the composer contributes a very useful

booklet note.

John Quinn

See also review by Robert Hugill

Support us financially by purchasing this disc from:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|