|

|

|

Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from: |

|

|

|

|

|

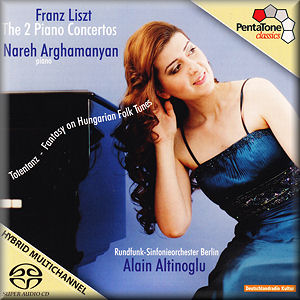

Franz LISZT

(1811-1886)

Piano Concerto No.1 in E flat major, S.124 (1830-49, rev. 1853,

1856) [18:48]

Piano Concerto No.2 in A major, S.125 (1839-40, rev. 1849, 1861)

[21:51]

Totentanz for piano and orchestra, S.126, R.457, (1839-49 with later

revisions) [15:38]

Fantasy on Hungarian Folk Tunes for piano and orchestra, S.123 (1852/53)

[15:33]

Nareh Arghamanyan (piano)

Nareh Arghamanyan (piano)

Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin/Alain Altinoglu

rec. Haus des Rundfunks, RBB Berlin, Germany, April 2012

PENTATONE CLASSICS

PENTATONE CLASSICS  PTC 5186 397 [72:24]

PTC 5186 397 [72:24]

|

|

|

Armenian soloist Nareh Arghamanyan studied at the University

of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna and was a winner of the

2008 Montreal International Music Competition. There are several

excellent orchestras in the city of Berlin and the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester

Berlin is certainly worthy of praise. It has made a number of

recent recordings for Pentatone. Paris-born conductor Alain

Altinoglu has conducted a number of prestigious orchestras including

productions at many international opera houses. He made his

New York Metropolitan debut in 2010 conducting Bizet’s Carmen.

Liszt made the first sketches for his Piano Concerto No.1

in 1830, undertaking serious work in Rome around 1839/40. He

seems to have completed it around 1849, making revisions in

1853 and further adjustments in 1856. Dedicated to the piano

virtuoso and composer Henry Litolff it would be hard to imagine

more eminent performers at its 1855 première at the Ducal Palace

in Weimar, Germany when the composer was soloist under the baton

of Hector Berlioz. Following its introduction influential music

critic Eduard Hanslick described the score as the “Triangle

Concerto” in response to the prominent triangle part in

the third movement. Cast in four movements and unfolding in

a single continuous span it is now firmly regarded as a warhorse

of the repertoire.

Of special note in the First Concerto is Arghamanyan’s

playing of the second movement Quasi adagio at times

so affectionate and intimate. Suddenly altering character the

music becomes stormy and forthright with Arghamanyan shifting

swiftly to a joyous and up-lifting mood. The sound of the infamous

triangle in the Allegretto vivace was barely audible.

This is light-hearted music that seems to canter along without

a care in the world with Arghamanyan confidently negotiating

the hazards along the way. With occasional bouts of seriousness

in the buoyant and jaunty writing of the final movement there

is spirited and assured playing. I loved the barnstorming Presto

conclusion.

Liszt began composing his Piano Concerto No.2 in 1839

in Rome, revising the score on at least two further occasions.

The first performance was given with Liszt conducting his pupil

Hans Bronsart (von Schellendorff) at Weimar in 1857. To highlight

the symphonic nature of the score it was described in the manuscript

as a “concerto symphonique”. Designed in a single continuous

span the A major Concerto is in six sections although

this recording is separated into four tracks. No less a figure

than Daniel Barenboim has expressed the view: “Although

less frequently played than the first, the second concerto is

no less a masterpiece.” With Arghamanyan and Altinoglu

I especially enjoyed the restless feel and quick tempo of the

opening movement. It generates a real sense of drama. The opening

of the Allegro agitato assai feels ominous building

to a compelling climax before moving to a relaxing world of

ease and comfort. I loved the windswept quality of the Allegro

deciso with its keen forward momentum and muscularity.

Most remarkable are the contrasting moods in the Finale

marked Marziale, un poco meno allegro. The

bravura conclusion is dramatic.

Over the years I have come across a large number of recordings

of the Liszt Piano Concertos. I especially admire the

marvellously exhilarating and highly confident accounts from

Krystian Zimerman and the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Seiji

Ozawa. Zimerman recorded the Liszt scores at the Symphony Hall,

Boston in 1987 with a warm and clear digital sound on Deutsche

Grammophon 423 571-2 (c/w Totentanz). I also have great

respect for the commanding live 2011 accounts from Daniel Barenboim

and the Staatskapelle Berlin under Pierre Boulez from the Essen

Philharmonie at the Ruhr Piano Festival. Barenboim provides

strong and assured performances that are often exhilarating

with Boulez and the Staatskapelle Berlin coming across as highly

responsive partners. The perfect scenario would be to own both

the Zimerman/Ozawa and the Barenboim/Boulez sets. One of the

lesser known recordings of the Liszt Concertos that

has given me much enjoyment is played with assured passion by

Arnaldo Cohen with the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra under John

Neschling. Cohen recorded the works in 2005 at São Paulo, Brazil

on BIS-SACD-1530 (c/w Totentanz).

It seems that Liszt was inspired to write his Totentanz

(Dance of death or Dance macabre) Paraphrase

on the ‘Dies irae’ for piano and orchestra,

S.126 by the magnificent frescoes titled ‘The Triumph of

Death’ on the wall of the basilica in the Campo Santo at

Pisa. The Totentanz comprises a series of variations

that embodies the plainchant of the ‘Dies Irae’. It

was first sketched out by Liszt around 1839 and completed by

1849 undergoing subsequent revision. Here the soloist shows

fine musicianship giving a most persuasive account that conveys

a wide range of colour and dynamic. The conclusion is both exhilarating

and highly dramatic. With regard to alternative recordings I

admire the stirring and confident performance from Krystian

Zimerman mentioned above.

Liszt’s Fantasy on Hungarian Folk Tunes for piano and orchestra,

S.123 (Hungarian Fantasy) composed in 1852/53 has a

similar style with comparable energetic rhythms to his renowned

Hungarian Rhapsodies. It’s a score that I experience as frequently

coarse, overblown and sometimes brash but always absorbing and

often thrilling. Arghamanyan is a most persuasive soloist. Of

the finest accounts of the Hungarian Fantasy I’m happy

to stay with Arghamanyan on Pentatone. As an alternative there

is the vibrant 1981 Philadelphia account from soloist Cyprien

Katsaris and the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy

on PIANO 21 P21 022-A.

The orchestra play convincingly throughout this disc demonstrating

keen concentration and splendid musicianship. The orchestral

colours are broad in range and spectacularly vivid.

Michael Cookson

Support

us financially by purchasing this disc from: |

|

|

|

|

|

|