|

|

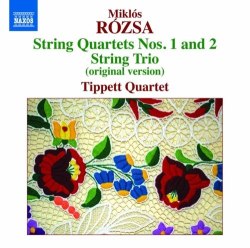

Miklós RÓZSA (1907-1995)

String Quartet No.2, Op.38 [20:39]

String Trio, Op.1 (original published version)* [30:00]

String Quartet No.1, Op.22 [24:20]

Tippett Quartet (John Mills and Jeremy Isaacs (violins), Julia O’Riordan (viola), Bozidar Vukotic (cello))

rec. St Paul’s Church, Southgate, London, UK, 22-24 November 2011

*World première recording

NAXOS 8.572903 [75:07]

Amongst some people there has always been a snobbery that holds that those composers who write for films cannot be classed as ‘serious’. These people hold that view even if the same composers also write music not intended for film.

Somehow those established composers who are contracted to write music for the odd film are exempt from this slur. Into the second category there is as varied a group as Bax, Bernstein, Bliss, Britten, Philip Glass, Sofia Gubaidulina, Alfred Schnittke, Walton, Prokofiev and Shostakovich, while the first includes John Williams, Ennio Morricone, Nino Rota, Bernard Herrmann, Eric Wolfgang Korngold and the composer of the music on this disc, Miklós Rózsa.

I hope, like me, that you have no time for such patent nonsense but should you need any convincing then this disc should do it at least in respect of this composer. I used the word ‘established’ to categorise those composers who had already made it in their chosen profession before they wrote for film or television. That seems to be the key point in the spurious argument about who should be classed as ‘serious’ as opposed to those who simply ‘write a bit of classical music on the side’.

Rózsa began as a serious composer of chamber works long before he moved, first to London to work with Alexander Korda and later to Hollywood where his reputation as a giant among composers of film music is unsurpassed. The problem was that those early works did not get sufficient exposure to cement his reputation in that sphere hence he was pigeonholed as a ‘film music composer’. I’ve been a fan for decades and found his autobiography, Double Life (1982), an utterly absorbing and fascinating read. In it I learned of the hoops that composers who work at the behest of the film moguls have to jump through and the time constraints imposed upon them. The cavalier way in which film directors and companies will simply cut or leave out some or at worst all the music written for a film or decide to credit other people with having composed it is also generally well documented. For such composers to then be written off as mere ‘film composers’ and have their other compositions dismissed by elements among the music establishment, including some ‘sniffy’ critics, must be almost unbearable.

While writing this review I’ve been listening to others of his works including his Concerto for Viola and Orchestra, Op.37 (1979) and Hungarian Serenade, Op.25 (1945) (Naxos 8.570925), his Variations on a Hungarian Peasant Song, Op.4 (1929), North Hungarian Peasant Songs and Dances, Op.5 (1929) and Sonata for Violin Solo, Op.40 (1986) (Naxos 8.570190) and his Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, Op.32 (1968) and Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Cello and Orchestra, Op.29 (1966) (ASV Gold GLD 4018), all of which are uniformly excellent. The two works written in the 1920s are from his youth when he yearned to be an acknowledged composer of classical chamber and orchestral works, whereas becoming a composer of music for the cinema was something he could not have imagined in his wildest dreams.

Back to the present disc: Rózsa’s second string quartet was written in 1981 at his summer retreat on the Italian Riviera, a place he found more conducive to composing his ‘serious’ music than Hollywood. He had been canny enough to have a summer break written into his contract with the studios. The first movement is anxious and agitated while the slow movement is quite bleak with viola and cello seeming to play apart from the two violins, hence its subtitle “2+2”. It has echoes of Hungarian folk themes. The brief scherzo which follows has more in it as well as humour which is a marked feature. The final movement Allegro risoluto embodies two contrasting ideas, one restless and driving and the other lyrically beautiful. These two apparently competing themes are neatly interwoven to bring the work to an exciting and abrupt conclusion.

His String Trio, here receiving the world première recording of its original published version from 1929, was composed in 1927. In his autobiography he acknowledged the fact that it contained “elements of immaturity” going on to say that while there were moments when he was “feeling [his] way ... the basic elements of my mature style are, in embryonic formations, unmistakably present already”. The opening moment contrasts two ideas, one agitated while the other, emerging after a couple of minutes from the cello, is a nostalgic theme. It has recognisably Hungarian roots as if he knew that later in life he would be living abroad while his heart remained in his native land. The second movement marked Gioioso (joyful) is in the form of a Hungarian dance, something he explored in several of his works in the same way as did both Bartók and Kodály. Rozsa’s use did not result from the collection of original material since it simply seemed to be part of his very being and couldn’t help emerge in his music. In fact he once wrote that the Hungarian folk idiom was “stamped indelibly in one way or another on virtually every bar [I] ever put on paper”. The third movement marked Largo con dolore is as described, full of anguishwith hints at the Hungarian melody from the first movement. That mood is dispelled as soon as the final movement begins with a capricious theme. This, after being fully explored, increases in intensity to conclude the work in a flurry of activity.

The final work on the disc is Rózsa’s first string quartet written in 1950 at which time he was working flat out on the music for MGM’s blockbuster Quo Vadis. He dedicated it to Peter Ustinov who played the would-be composer Nero. A greater contrast in music one could hardly imagine with his music for the film being monumental in its scope as befits a film in ‘glorious Technicolor’ about the glory that was Rome. The string quartet reflects the private world of a composer whose heart was still in Hungary. Its opening movement has a wistful and nostalgically Hungarian theme which is beautifully laid out. The second, marked Scherzo in modo ongarese, is a simply fabulous whirling Hungarian dance that, as is typical of that country’s folk music, suddenly changes in tempo and slows down to become reflective in contrast.The third movement Lento in the form of a nocturne is also reflective, even darkly and achingly so. As the excellently informative booklet notes by Frank K. DeWald say, it was written while the composer was sailing back to the USA from Europe, where he had been in Rome working on Quo Vadis. He was feeling particularly homesick for his native land which he had left so many years before. The last movement recalls themes from the previous movement in the form of a dance. It begins in a fast tempo before a more lyrical mood is introduced. The tension created between these competing ideas is maintained throughout with the urgent nature gaining the upper hand to finish on a final furious dash upwards in a spiral of notes.

I trust that anyone who is not already convinced that this composer truly deserves recognition as a great one whose contribution is highly valuable will be won over by the superb music on this disc. The musicians playing it do so with verve, enthusiasm and a passion that is evident throughout.

Steve Arloff

|

|

|